Prix : 15,00 €TTC

01-2024, tome 121, 1, p.7-34 - Klaric L., Ducasse S., Langlais M. (2024) – Pourquoi l’homme sans arc devrait-il chercher des flèches ? Discuter une hypothèse non parcimonieuse : le cas de l’arc à la Grotte Mandrin (Paléolithique supérieur initial)

Pourquoi l’homme sans arc devrait-il chercher des flèches ?

Discuter une hypothèse non parcimonieuse :

le cas de l’arc à la Grotte Mandrin (Paléolithique supérieur initial)

Laurent Klaric, Sylvain Ducasse, Mathieu Langlais

Résumé : En Préhistoire, au delà de trouvailles inattendues faites dans des contextes clairs, il arrive que les découvertes ou résultats d’étude « extraordinaires » soient sujet à controverses. Cela reflète en général la difficulté qu’ont les archéologues à s’accorder sur le degré de précision et la construction de leur argumentation. De manière concomitante, une certaine surmédiatisation vise parfois à informer et convaincre le public de l’importance d’une découverte jugée majeure par ses auteurs, sans que, pour autant, le résultat ne remporte une large adhésion de la communauté scientifique. Constituant un exemple de la dérive sensationnaliste évoquée, une étude récente (Metz et al., 2023) consacrée aux pointes et micro-pointes du niveau E de la Grotte Mandrin (Malataverne, Drôme) vient de conclure à l’usage de l’arc il y a 54 000 ans par un groupe Homo sapiens en vallée du Rhône. Ce résultat proclame ainsi le vieillissement de près de 40 000 ans de l’usage reconnu de l’arc en Europe. Une lecture attentive de cette étude ne nous a pas convaincu de la validité de ce résultat « extraordinaire » qui nous semble a priori incompatible avec le principe de parcimonie. C’est sur la base du raisonnement et de la logique argumentaire que nous proposons une réfutation du mode de propulsion inféré qui est en grande partie fondée sur un « postulat d’efficacité » au détriment d’autres données archéologiques pourtant disponibles sur le site. Nous exposons une réfutation basée sur : 1) les données présentées dans l’étude ainsi qu’à l’occasion d’autres travaux antérieurs sur les armes préhistoriques, 2) des observations ethnographiques issues de trois continents et relatives à la chasse et son apprentissage par les enfants, 3) une régularité générale touchant à l’apprentissage dans les sociétés d’Homo sapiens. À l’issue de notre réflexion, nous proposons que les pointes microlithiques de Mandrin puissent correspondre à des parties d’armes miniatures potentiellement attribuables à l’activité des enfants.

Mots-clés : Paléolithique supérieur, industrie lithique, armement, chasse, apprentissage, enfants, microlithisation, miniature, argumentation, ethnographie.

Abstract: In Prehistory, beyond unexpected finds made in clear contexts, “extraordinary” discoveries or study results are sometimes the subject of controversy. The latter generally reflect the difficulty archaeologists often have in agreeing on the degree of precision and construction of their arguments. From the age of humankind to the settlement patterns of the Americas, the “modernity” of Homo sapiens and the role of women in prehistory, bold hypotheses and startling conclusions follow one another in the wake of media fashions. At the same time, there may be a certain amount of media hype aimed at informing and convincing the public of the importance of a discovery deemed major by its authors, although the announced result may not be widely supported by the academic community. A recent study (Metz et al., 2023) devoted to the points and micro-points of level E of the Mandrin Cave (Malataverne, Drôme) is just one example of the sensationalist drift mentioned above. It concludes that the bow was used 54,000 years ago by a group of Homo sapiens in the Rhône Valley. The spectacular result proclaims that the recognized use of bow and arrow in Europe is circa 40,000 years older than previously known. However, a careful reading of this study did not convince us of the validity of this “extraordinary” result, which seems to us a priori incompatible with the principle of parsimony. Indeed, the article by Metz and colleagues would require further comment on the technical aspects of the study (e.g. criteria for morpho-typological and productional distinction of flint points, reality of the existence of a nano-point component, criteria about the functional analysis, details of the parameters of the Initiarc experiment). However, we have chosen to accept as valid the hypothesis that a large proportion of the points analysed correspond to axial tip of hunting projectiles. It is therefore on the basis of reasoning and argumentative logic that we propose a refutation of the use of bow and arrow 54,000 years ago on the Mandrin site. Indeed, the conclusion of the study by L. Metz and colleagues is essentially based on a “postulate of effectiveness” that ignores certain other archaeological data available on the site. We therefore first propose a rebuttal based on 1/ the data presented in the study and in other works about to prehistoric weapons, 2/ ethnographic data from three continents relating to traditional hunting and the place of children in this activity, and 3/ a general regularity concerning learning in present-day Homo sapiens societies.

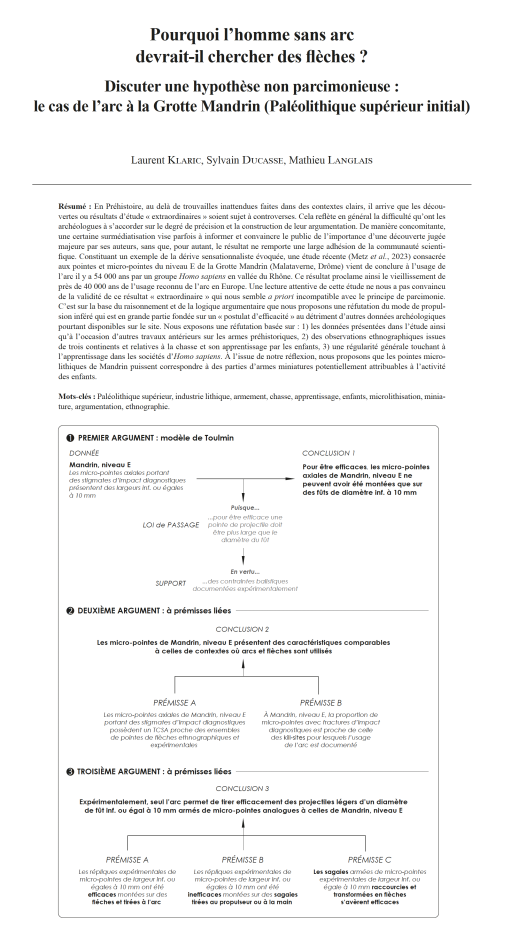

Firstly, we analyse the arguments used by L. Metz and colleagues, presenting them from the point of view of argumentative logic, using the categories explained in C. Plantin's dictionary of argumentation (Plantin, 2021). This analyse leads us to distinguish between the main arguments in the Metz et al. demonstration (archaeological impact fractures similar to those used in the experiment, the “rule” that the diameter of the projectile shaft is necessarily less than the width of the point, the use of the bow for maximum penetration efficiency of a light projectile, calculation of the TCSA) and the premises on which the demonstration is based. We show not only the weakness or artificiality of some of the arguments/premises presented, but also the “argumentation by default” nature of the demonstration put forward by L. Metz and colleagues, since no new decisive argument is proposed that would allow a direct and differential diagnosis of bow use (as opposed to spearthrower or bare-handed use).

The entire demonstration is based on the necessity of using the bow to ensure optimal penetration of projectiles armed with micro- and nano-points. This reasoning by default implies a condition of refutability: the demonstration is only valid if the small lithic points were necessarily intended to be effective from the point of view of the projectile penetrating into its target.

We then show that there are many examples among traditional hunters of the ethnographic register of miniature children's weapons, more or less faithful replicas of those used by adults, which constitute children's play or hunting training equipment. These children's weapons are not necessarily intended to be lethal or as effective as those used by adults (i.e. penetration of the tip into a living animal target is not a major requirement, since the main targets are often inanimate for beginners), but they are often functional enough for shooting, practising and playing. In fact, they can reasonably sustain damage during these uses. This simple explanation, which does not imply that the bow was used 40,000 years earlier than archaeologically attested, has not been considered or tested in Metz and colleagues study. At the end of our analysis, we propose that the Mandrin microlithic points of level E could correspond to tip of miniature weapons that could potentially be used by children. It would, of course, be necessary to ensure that such miniatures could break in the same way as adult weapons when used by children on inanimate target. However, it seems to us that, given the current state of knowledge, this hypothesis is undoubtedly more parsimonious than that of the use of bows and arrows 40,000 years earlier than currently documented in the archaeological record at Stellmoor in Germany. Through this example, we finally underline the excesses of a certain number of sensational studies and publications with a wide international audience, where a critical reading of the arguments would often prevent the promotion of non parsimonious hypotheses as solidly established scientific results.

Keywords: Upper Palaeolithic, lithic industry, weaponry, hunting, apprenticeship, children, microlithism, miniature, argumentation, ethnography.