- La SPF

- Réunions

- Le Bulletin de la SPF

- Organisation et comité de rédaction

- Comité de lecture (2020-2025)

- Ligne éditoriale et consignes BSPF

- Données supplémentaires

- Annoncer dans le Bulletin de la SPF

- Séances de la SPF (suppléments)

- Bulletin de la SPF 2025, tome 122

- Bulletin de la SPF 2024, tome 121

- Bulletin de la SPF 2023, tome 120

- Bulletin de la SPF 2022, tome 119

- Archives BSPF 1904-2021 en accès libre

- Publications

- Newsletter

- Boutique

Prix : 15,00 €TTC

08-2022, tome 119, 2, p.295-324 – Escola M (2022) – La chirurgie crânienne du Néolithique alsacien : état de la question

Escola M (2022) - La chirurgie crânienne du Néolithique alsacien : état de la question

Résumé : Les connaissances acquises sur le mode de vie des premières populations néolithiques alsaciennes sont dues à une conjoncture favorable : l'expansion du courant néolithique danubien, la forte implantation humaine dans les plaines de loess, la bonne conservation de milliers de tombes et l'exploitation récente des terres à des fins de constructions immobilières. Ces conditions optimales ont conduit à la découverte et à l'étude de quatre cas alsaciens attribués à des actes chirurgicaux.

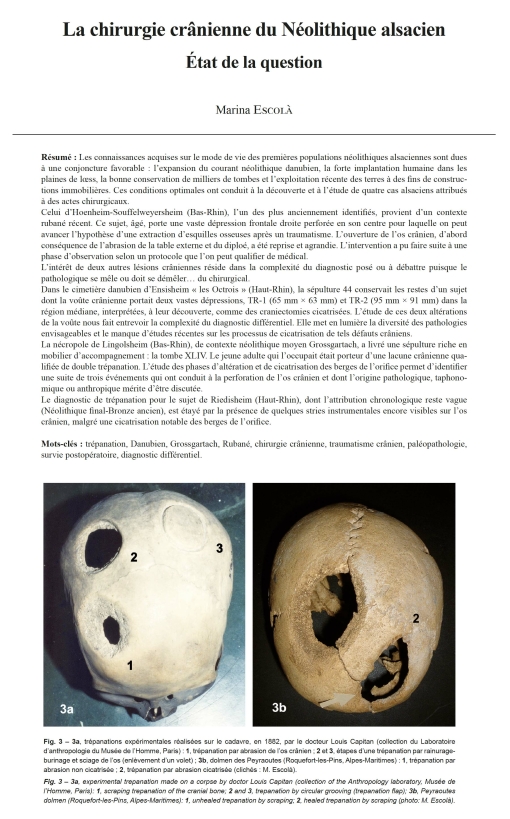

Celui d'Hoenheim-Souffelweyersheim (Bas-Rhin), l'un des plus anciennement identifiés, provient d'un contexte rubané récent. Ce sujet, âgé, porte une vaste dépression frontale droite perforée en son centre pour laquelle on peut avancer l'hypothèse d'une extraction d'esquilles osseuses après un traumatisme. L'ouverture de l'os crânien, d'abord conséquence de l'abrasion de la table externe et du diploé, a été reprise et agrandie. L'intervention a pu faire suite à une phase d'observation selon un protocole que l'on peut qualifier de médical.

L'intérêt de deux autres lésions crâniennes réside dans la complexité du diagnostic posé ou à débattre puisque le pathologique se mêle ou doit se démêler" du chirurgical.

Dans le cimetière danubien d'Ensisheim « les Octrois » (Haut-Rhin), la sépulture 44 conservait les restes d'un sujet dont la voûte crânienne portait deux vastes dépressions, TR-1 (65 mm × 63 mm) et TR-2 (95 mm × 91 mm) dans la région médiane, interprétées, à leur découverte, comme des craniectomies cicatrisées. L'étude de ces deux altérations de la voûte nous fait entrevoir la complexité du diagnostic différentiel. Elle met en lumière la diversité des pathologies envisageables et le manque d'études récentes sur les processus de cicatrisation de tels défauts crâniens.

La nécropole de Lingolsheim (Bas-Rhin), de contexte néolithique moyen Grossgartach, a livré une sépulture riche en mobilier d???accompagnement : la tombe XLIV. Le jeune adulte qui l'occupait était porteur d'une lacune crânienne qualifiée de double trépanation. L'étude des phases d'altération et de cicatrisation des berges de l'orifice permet d'identifier une suite de trois événements qui ont conduit à la perforation de l'os crânien et dont l'origine pathologique, taphonomique ou anthropique mérite d'être discutée.

Le diagnostic de trépanation pour le sujet de Riedisheim (Haut-Rhin), dont l'attribution chronologique reste vague (Néolithique final-Bronze ancien), est étayé par la présence de quelques stries instrumentales encore visibles sur l'os crânien, malgré une cicatrisation notable des berges de l'orifice.

Mots-clés : trépanation, Danubien, Grossgartach, Rubané, chirurgie crânienne, traumatisme crânien, paléopathologie, survie postopératoire, diagnostic différentiel.

Abstract: TThe expansion of the Danubian Neolithic, the dense settlement in the loess plains, the preservation of thousands of graves and the recent development of preventive archaeology have greatly increased our knowledge of the first Neolithic peoples??? way of life in Alsace. If we consider the Mesolithic people of North Africa (Taforalt, Maroc) and Ukraine (Vasiliyevka II and III. ; Vovnigi II) as precursors of cranial surgery, the first Danubian (Vedrovice, Moravie) and Mediterranean Neolithic people (abri Pendimoun, Castellar, Var) show early use of trepanation to treat trauma or other pathologies. Four cases of this surgical procedure found in archaeological contexts in Alsace have been published.

One of the oldest identified cases comes from a recent Rubane cemetery at Hoenheim-Souffelweyersheim (Bas-Rhin). One of the graves housed an old man with a large right frontal depression with a perforation in the centre. Bone splinters seem to have been extracted after the trauma occurred.

The operative choice was that of an abrasion of the external table and the diploe. However, it is difficult to comment on the origin of the perforation, choice or consequence of the bone thinning. Another skull from the same site bears the marks of an impact framed by two incisions.

For these two cases, an observation phase preceded the choice of the medical protocol.

Other cranial lesions observed on Early and Middle Neolithic subjects from Alsace show the difficulty of the diagnosis with the pathological aspects having to be disentangled from the surgical aspects.

In the Danubian cemetery of Ensisheim "Les Octrois" in the Haut-Rhin, tomb 44 yielded the remains of a subject whose cranial vault shows two large depressions TR-1 (6.5 mm x 63 m) and TR-2 (95 mm x 91 mm), located on the central axis and interpreted upon discovery as scarred craniectomies. The diagnosis for TR-1 was mainly based on the newly formed bony laminae that would have covered the entire bony surface of the opening. Observation of this arch defect identifies a raised centre around which radiate five depressions. The diagnosis proposed by K. W. Alt and collaborators (1997) involved the perforation being made by successive circular scrapings and the said perforation would have been filled with scarred bone. Similar frontal alterations, published in the anthropological literature, have been the subject of different diagnoses. Significant healed frontal trepanations are known for the periods ranging from the Late Neolithic to the Bronze Age (at the Trou de Goujout in Teyjat, in the Dordogne, for example). Healed, they show no filling ofthe gap. The differential diagnosis for this TR-1 defect could point to osteolytic erosion of the cranial vault followed

by scarring. The TR-2 alteration was interpreted by the authors as a partially healed trepanation with a procedure consisting of an act of scraping after the development of four linear incisions defining a surface of the external table.

Other pathologies, initiating osteolysis of the cranial vault, cannot be excluded, including that of a traumatic episode leading to hematoma and that of osteitis, which subsequently healed, due or not to human intervention. Whatever the possible diagnosis, that of the bone growth was effective enough to fill such a large area has, to our knowledge, never been mentioned in neurosurgery or paleoanthropology papers (Nerlich et al., 2003 ; Partiot et al., 2020). It is therefore necessary, in the future, to look at the healing and regrowth processes of cranial bone in the light of a well-supported differential diagnosis.

The necropolis of Lingolsheim (Bas-Rhin) dating to the Middle Neolithic Grossgartach yielded the burial of a young adult with rich grace goods. The individual had a cranial lacuna described as a double trepanation (Forrer, 1938). The loss of bone affects the bregma, the left parietal and slightly the right parietal. The phases of alteration and healing of the edges of the orifice make it possible to identify a series of events that led to the perforation of the cranial bone and

its pathological, taphonomic or anthropogenic origin provides subject for discussion. Chronologically, three episodes probably shaped this cranial opening. Firstly, a localized osteolytic lesion of exocranial development, well circumscribed, led to a bregmatic perforation of the two tables and of the diploe. The only observation of the edge, abrupt, without

bevel, with a slightly sinuous, jagged outline and an apparent diploe and a blunt ridge, could suggest the pathological and osteolytic origin of this perforation. The use of an interactive tool has made it possible to support this differential diagnosis (Partiot et al., 2017). Menigocele, gliocele cyst and isolated eosinophilic granuloma (Langerhansian histiocytosis) are pathologies that may have generated this orifice; but due to the lack of a possible histological analysis, this

remains hypothetical. A surgical opening made in two phases by grooving-chiseling widened the gap, which was of pathological origin. The first opening, according to the healing of its bevel was cut on the left parietal. The only trace of this surgical act, a 12 mm length fragment of a slightly inclined external bevel, is completely healed. A second intervention

enlarged the scarred opening. The hypothesis of post-mortem cutting or trepanation followed by immediate death can be rejected as the blunt edges of the two bone tables attest to an engaged healing process. We cannot exclude the possible link between these two interventions and the pathological orifice. Coalescence and the development of tumours from an eosinophilic granuloma may have warranted the second intervention, following external manifestations of soft tissue swelling. The surgical opening therefore includes two operations and not just one as was initially mentioned. The first individual survived the intervention by several years whereas the second only for a few months.

The trepanned individual from Riedisheim (Haut-Rhin) is the most recent from Alsace. The archaeological context remains vague, Final Neolithic or Early Bronze Age, for this burial discovered during quarry work around 1888. A roughly triangular parietal gap occupies the centre of a large abraded cranial surface that evokes an act of the thinning of the vault followed by an action of cutting a shutter or enlarging the orifice. The cut marks that are still visible despite notable scarring of the edges indicate trepanation.With this overview, we note that these surgical acts remain rare in Alsace in relation to the total number of burials dating

from the Early Neolithic to the Bronze Age. There is no local extension of the practice. Most of the individuals survived the interventions that would have been the treatment for trauma or pathology. The case from Ensisheim may have been a surgical act, but in this specific case, the marks do not seem to be due to healed trepanations and an additional study is needed.

Keywords: Trepanation, Danubian cultures, Grossgartach culture, Linear pottery culture, cranial surgery, head injury, paleopathology, post-surgical survival, differential diagnosis.

Autres articles de "Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française 2022"

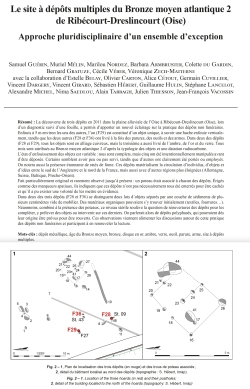

16-2022, tome 119, 4, p.633-720 - Guérin S., Mélin M., Nordez M., Armbruster B., Du Gardin C., Gratuze B., Véber C., Zech-Matterne V. (2022) – Le site à dépôts multiples du Bronze moyen atlantique 2 de Ribécourt-Dreslincourt (Oise) : approche pluridiscipl

Le site à dépôts multiples du Bronze moyen atlantique 2 de Ribécourt-Dreslincourt (Oise) Approche pluridisciplinaire d'un ensemble d'exception

Samuel Guérin, Muriel Mélin, Marilou Nordez, Barbara Armbruster, Colette du Gardin, Bernard Gratuze, Cécile Véber, Véronique Zech-Matterne

avec la collaboration d???Estelle Belay, Olivier Carton, Alice Cétout, Germain Cuvillier, Vincent Dargery, Vincent Girard, Sébastien Hébert, Guillaume Hulin, Stéphane Lancelot, Alexandre Michel, Nima Saedlou, Alain Tabbagh, Julien Thiesson, Jean-François Vacossin

Résumé : La découverte de trois dépôts en 2011 dans la plaine alluviale de l'Oise à Ribécourt-Dreslincourt (Oise), lors d'un diagnostic suivi d'une fouille, a permis d'apporter un nouvel éclairage sur la pratique des dépôts non funéraires. Enfouis à 5 m environ les uns des autres, l'un (F29) est constitué d'un objet unique, à savoir une hache enfouie verticalement, tandis que les deux autres (F28 et F36) ont livré à la fois des parures, des outils et des armes. Dans deux des dépôts (F28 et F29), tous les objets sont en alliage cuivreux, mais le troisième a aussi livré de l'ambre, de l'or et du verre. Tous trois sont attribués au Bronze moyen atlantique 2 d'après la typologie des objets et une datation radiocarbone.

L'état d'enfouissement des objets est variable : tous sont complets, mais cinq ont été intentionnellement manipulés avant d'être déposés. Certains semblent avoir peu ou pas servi, tandis que d'autres ont clairement été portés ou employés. On notera aussi la présence étonnante de ratés de fonte. Ces dépôts matérialisent la circulation d'individus, d'objets et d'idées entre le sud de l'Angleterre et le nord de la France, mais aussi avec d'autres régions plus éloignées (Allemagne, Suisse, Baltique, Proche-Orient).

Fait particulièrement original et rarement observé jusqu'à présent : un poteau était associé à chacun des dépôts. Érigés comme des marqueurs spatiaux, ils indiquent que ces dépôts n'ont pas nécessairement tous été enterrés pour être cachés et qu'il a pu exister une volonté de les mettre en évidence.

Dans deux des trois dépôts (F28 et F36) se distinguent deux lots d'objets séparés par une couche de sédiments de plusieurs centimètres vide de mobilier. Des matériaux organiques pouvaient s'y trouver initialement (textiles, fourrures...). Néanmoins, combiné à la présence des poteaux, ce niveau stérile soulève la question de réouvertures des dépôts pour les compléter, y prélever des objets ou intervenir sur ces derniers. On parlerait alors de dépôts polyphasés, qui pourraient dès leur origine être prévus pour être rouverts. Ces observations viennent alimenter les discussions autour de cette pratique des dépôts non funéraires et participent à en renouveler la lecture.

Mots-clés : dépôt métallique, âge du Bronze moyen, bronze, disque en or, ambre, verre, outil, parure, arme, site à dépôts multiples.

Abstract: The excavation, in situ and in laboratory, of three Middle Bronze Age hoards discovered in 2011 in the alluvial plain of the Oise at Ribécourt-Dreslincourt (Oise) has provided the opportunity to reflect on these particular Bronze Age sites.

The three hoards (F28, F29 and F36) were buried at one end of a small triangular area. Each hoard is located near a post-hole. This disposition has never been observed in France until now. The hoards are unusual as they include objects made from materials such as gold, amber, glass and bronze and some of the objects themselves are unique. They include a hammer with a twisted decoration, a pin with two large discs and a gold disc. The Baltic origin of the amber from hoard F36 is of particular interest (a prestigious material) as well as the nodules of raw material. The variety of objects should be underlined as they fall into four functional categories: weaponry (two daggers), tools (two axes and a hammer), ornaments (eleven bracelets, a pin, three torques, twenty-seven elements strung on a probable necklace) and the gold disc (part of a possible ritual object). Some of these objects appear to have had little or no use, while others are clearly used. Also of note is the presence of miscasts.

The disposition of the objects shows rarely observed gestures. In the case of hoard F29, a single metal object is buried, an axe placed vertically, cutting edge upwards. For hoard F28, the stringing of six bracelets on the handle of a dagger stuck vertically into the base of the feature is noteworthy. Concerning hoard F36, the most significant object arrangement is a compact pile of artefacts stacked in the middle of the pit, including a bent pin (36.38) enclosing four bracelets (36.34 to 37) as well as a twisted torque (36.33), itself bent and broken into three fragments. We have also observed pre-depositional manipulations. The state of the objects at the time of their burial is variable: all are complete, but five were manipulated before being deposited. In addition to the cluster of objects described above, the dagger 36.26, which is missing the two rivets that hold its handle, may have been dismantled before burial, while the gold disc, a bipartite object, is missing its bronze support.

Hoards F28 and 36A have a particular disposition with an intermediate layer devoid of objects. This could be due to the presence of organic material that has now disappeared or because the pit containing the hoard was reopened at a later date in order to deposit a new set of objects on top. The addition of items could have been planned from the outset as with the multi-phased hoards of Grunty Fen (Cambridgeshire, UK) and Spaxton (Somerset, UK). Objects from the Ribécourt-Dreslincourt hoards, suggest that the three are contemporary, which does not imply that the deposits were simultaneous. The timeline could extend over a century according to the typochronological coherence of the objects.

The Ribécourt-Dreslincourt hoards are attributed to the Atlantic Middle Bronze Age 2. The annular ornaments are quite characteristic of this period, as are the palstaves. Although the typology of the other objects is less obvious, it does not contradict this chronological positioning. Radiocarbon analysis also confirms this date (1442-1302 cal BC). The hoards belong to the rather rare category in the Atlantic area of multi-type hoards that bring together different objects, as is the case for the Villers-sur-Authie (Somme) hoard, now disappeared, or the Wylye (Wiltshire, UK) and Hollingbury Hill (Sussex, UK) hoards. The typology of the annular ornaments from the Ribécourt-Dreslincourt hoards shows that the objects come from different areas, the south-east of England, the Armorican Massif, as well as the lower and middle basins of the Seine and Somme rivers. We can also draw a direct parallel between the 36.36 bracelet and anklets from graves in the Lüneburg region (Lower Saxony), or from Schleswig-Holstein in Germany. Comparisons for the pin lead us to southern Germany and Switzerland, while the gold disc is similar to objects from the Nordic Bronze Age area (Denmark, northern Germany and the British Isles). The hoards' composition sheds light on the movement of individuals, objects and ideas between the south of England and the north of France, but also on relations with other more distant regions (Germany, Switzerland), whereas the amber and glass refer to the Baltic and the Near East regions.

To conclude, the fact that posts originally marked the Ribécourt-Dreslincourt hoards shows an underlying intention to make these hoards visible: they were not buried to be concealed. This ostentatious dimension goes hand in hand with the intention of sacralising particular places where interventions subsequent to the deposits would have taken place.

Keywords: metal hoard, Middle Bronze Age, bronze, gold disc, amber, glass, tool, ornament, weapon, multiple hoard site.

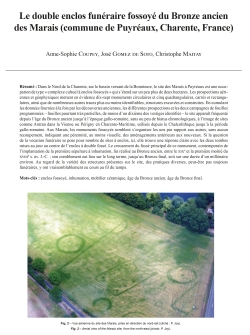

15-2022, tome 119, 4, p.635-662 - Coupey A.-S., Gomez de Soto J., Maitay C. (2022) – Le double enclos funéraire fossoyé du Bronze ancien des Marais (commune de Puyréaux, Charente, France)

Le double enclos funéraire fossoyé du Bronze ancien des Marais (commune de Puyréaux, Charente, France)

d'Anne-Sophie Coupey, José Gomez de Soto, Christophe Maitay

Résumé : Dans le Nord de la Charente, sur le bassin versant de la Bonnieure, le site des Marais à Puyréaux est une occupation de type « complexe cultuel à enclos fossoyés » qui s'étend sur un peu plus de deux hectares. Les prospections aériennes et géophysiques mettent en évidence dix-sept monuments circulaires et cinq quadrangulaires, carrés et rectangulaires, ainsi que de nombreuses autres traces plus ou moins identifiables, structures excavées et construites. En cumulant les données fournies à la fois par les découvertes anciennes, les différentes prospections et les deux campagnes de fouilles programmées - fouilles pourtant très partielles, de moins d'un dixième des vestiges identifiés - le site apparaît fréquenté depuis l'âge du Bronze ancien jusqu'à l'époque gallo-romaine, sans ou peu de hiatus chronologiques, à l'image de sites comme Antran dans la Vienne ou Périgny en Charente-Maritime, utilisés depuis le Chalcolithique jusqu'à la période

gallo-romaine. Aux Marais, les monuments fossoyés semblent s'organiser les uns par rapport aux autres, sans aucun recoupement, indiquant une pérennité, au moins visuelle, des aménagements antérieurs aux nouveaux. Si la question de la vocation funéraire se pose pour nombre de sites à enclos, ici, elle trouve une réponse claire avec les deux tombes mises au jour au centre de l'enclos à double fossé. Le creusement du fossé principal de ce monument, contemporain de l'implantation de la première sépulture à inhumation, fut réalisé au Bronze ancien, entre le xixe et la première moitié du xviiie s. av. J.-C. ; son comblement eut lieu sur le long terme, jusqu'au Bronze final, soit sur une durée d'un millénaire environ. Au regard de la variété des structures présentes sur le site, des pratiques diverses, peut-être pas toujours funéraires, y ont vraisemblablement eu cours au fil du temps.

Mots-clés : enclos fossoyé, inhumation, mobilier céramique, âge du Bronze ancien, âge du Bronze final.

Abstract: Les Marais in Puyréaux is a ritual complex with ditched enclosures spread over a little more than two hectares located on the watershed of the Bonnieure in the North of the Charente. Aerial and geophysical surveys show 17 circular and 5 quadrangular monuments, as well as numerous other more or less identifiable archaeological features. The data from old discoveries, surveys and two very partial programmed excavations indicate that the site was occupied almost continually from the early Bronze Age to the Roman period. This timeframe is similar to sites such as Antran, in Vienne or Perigny, in Charente-Maritime that date from the Chalcolithic to the Roman period. On the site of Les Marais, the spatial organisation of the ditched enclosures sees no overlap indicating that the older monuments were still visible when the newer enclosures were built. Unlike other monumental sites, this site is clearly a cemetery as two burials were found inside a double ditched enclosure.

The first burial dating from 1900 to 1740 BC is that of an adult of undetermined sex housed in a quadrangular pit with rounded corners. The individual lay on their left side in a flexed position in a covered wooden container surrounded by limestone blocks. A later burial dating from 1890 to 1680 BC cut the first burial above and slightly to the north-east. A number of stones from the first grave were "borrowed" to construct the later burial that probably contains a female with their head towards the west-north-west. This grave was reopened between 1730 - 1690 and 1510 BC, to bury a young adult (probably male) top to tail compared to the previous body the bones of which were placed at one end of the pit to make way for the new burial. The only preserved artefact is a bone pendant found under the skull in the female burial.

The main ditch of this monument dug to enclose the first burial, dates to the Early Bronze Age. Pottery found in the different layers of the fill indicate that it was backfilled gradually over a long period and completely filled in by the Late Bronze Age. There are three stratigraphic phases. The first layer at the bottom of the fill, devoid of any artefact, was formed from the erosion of the sandy and gravely cut of the ditch. The second layer contained the oldest pottery sherds (but no complete vessels), deposited intentionally or not. The assemblage includes several sherds from large presentation plates but mainly sherds from cooking and storage vessels. The most notable artefact is a disc cut in a thick potsherd from a large vessel and seems to be the oldest discovery for this kind of object. The third and last fill provides most of the pottery that is not chronologically homogeneous. The pottery dates from three phases of the Bronze Age: a fragment from a rounded bottom vessel dates to the Middle Bronze Age, a fragment from a plate dates to the Late Bronze Age Ib-IIa/BzD1b-Ha A1 and another plate fragment to the Late Bronze Age IIIa-IIIb/Ha B1-B2-3.

Regarding the circular enclosures, architectural transformations such as the building of a crown of stones on top of the main ditch could underline a change of the monument's function from funerary to ritual.

The variety of features on the Marais site, could indicate the change in use of the site over time, such as the original large sub-rectangular ditched enclosure of unknown function (33m on 20 m) similar to the Late Bronze Age Langgräbe. It has an « entrance with antenna » on one of its short sides with two curved advances and central interruption. This feature has yet to be excavated or dated.

Keywords: ditched enclosure, burial, pottery, Early Bronze Age, Late Bronze Age.

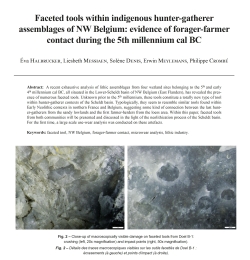

14-2022, tome 119, 4, p.605-633 - Halbrucker E., Messiaen L. Denis S., Meylemans E., Crombé P. (2022) – Faceted tools within indigenous hunter-gatherer assemblages of NW Belgium: evidence of forager-farmer contact during the 5th millennium cal BC

Faceted tools within indigenous hunter-gatherer assemblages of NW Belgium: evidence of forager-farmer contact during the 5th millennium cal BC

d'Éva Halbrucker, Liesbeth Messiaen, Solène Denis, Erwin Meylemans, Philippe Crombé

Abstract: A recent exhaustive analysis of lithic assemblages from four wetland sites belonging to the 5th and early 4th millennium cal BC, all situated in the Lower-Scheldt basin of NW Belgium (East Flanders), has revealed the presence of numerous faceted tools. Unknown prior to the 5th millennium, these tools constitute a totally new type of tool within hunter-gatherer contexts of the Scheldt basin. Typologically, they seem to resemble similar tools found within Early Neolithic contexts in northern France and Belgium, suggesting some kind of connection between the last hunter-gatherers from the sandy lowlands and the first farmer-herders from the loess area. Within this paper, faceted tools from both communities will be presented and discussed in the light of the neolithization process of the Scheldt basin. For the first time, a large scale use-wear analysis was conducted on these artefacts.

Keywords: faceted tool, NW Belgium, forager-farmer contact, microwear analysis, lithic industry.

Résumé : Une étude exhaustive a été récemment conduite sur quatre assemblages lithiques provenant de sites découvertes dans les zones humides du bassin inférieur de l'Escaut, localisé dans le Nord-Ouest de la Belgique (Flandre orientale). Ces quatre sites datent du 5e et du début du 4e millénaire avant notre ère. L'étude a révélé la présence de nombreux outils facettés, complètement inconnus jusqu'alors. Ils constituent donc un type d'outil nouveau chez ces communautés de chasseurs-cueilleurs du bassin de l'Escaut. Or, ces outils sont connus chez les premières populations agro-pastorales du Bassin parisien et de Moyenne Belgique. Ils pourraient alors se révéler cruciaux pour mieux comprendre les rapports entretenus entre les derniers chasseurs-cueilleurs des basses terres sablonneuses des Flandres et les premiers agro-pasteurs néolithiques des régions loessiques plus au sud.

Cet article propose une étude inédite de ces pièces facettées qui inclut, pour la première fois, une analyse tracéologique de grande ampleur. Celle-ci repose sur la constitution d'un premier référentiel expérimental. Ce référentiel rassemble 337 minutes d'utilisation concernant 13 outils facettés. Ils ont principalement été utilisés pour écraser et broyer. Ces outils expérimentaux ont été testés sur des céramiques, du grès, du poisson, des os frais et brûlés (vache et cerf), et des carcasses de canards colverts. Les céramiques ont été concassées sur une dalle de grès afin de produire du dégraissant de différentes granulométries. La surface de la même dalle de grès a ensuite été piquetée pour la raviver. Les outils expérimentaux ont également été utilisés pour retirer les nageoires et les têtes de plusieurs carpes. De plus, ils ont été employés pour extraire la moelle d'os frais. Une autre expérimentation a permis la production de dégraissant d'os brûlés. Enfin, deux outils ont été utilisés pour désarticuler les carcasses de deux colverts et écraser les os creux pour en extraire la moelle. La sélection des matériaux des enclumes constitue une autre variable prise en compte lors des expérimentations.

Sur cette base, 69 outils facettés archéologiques ont ensuite été analysés. 48 proviennent des sites mésolithiques du bassin inférieur de l'Escaut et 21 proviennent du site Blicquy/Villeneuve-Saint-Germain de Vaux-et-Borset localisé dans l'Est de la Belgique. Cela permet alors une comparaison directe entre les outils des communautés d'agro-pasteurs et des chasseurs-cueilleurs. Notre analyse s'est déclinée en deux volets : l'analyse typo-technologique basée sur des études antérieures a été enrichie de l'analyse tracéologique inédite.

Nos résultats montrent que ces outils facettés, innovation en contexte Swifterbant, représentent environ 10 % de la panoplie des outils chez ces communautés. Cette proportion est tout à fait comparable à celle des sites blicquiens du Hainaut et de Vaux-et-Borset. Les outils facettés apparaissent en très petites quantités à la fin du Rubané mais c'est durant la culture Blicquy/Villeneuve-Sait-Germain qu'ils se multiplient dans certaines régions, notamment le Bassin parisien et la Belgique où ils peuvent constituer jusqu'à 20 % des assemblages. Par ailleurs, les différentes catégories typo-technologiques distinguées dans les contextes BQY/VSG semblent également présentes dans le bassin de l'Escaut. Leurs proportions respectives sont difficilement comparables, car les catégories typo-technologiques doivent être précisées par les données fonctionnelles (résultats de l'analyse tracéologique). Mais quoiqu'il en soit, les formes et les dimensions semblent comparables entre les sites néolithiques et mésolithiques. Ainsi, il ressort de la présente étude que les outils facettés du bassin de l'Escaut présentent des similitudes morphométriques avec ceux découverts dans des contextes du Néolithique ancien dans la zone loessique de la Belgique moyenne et du Nord de la France. Plus intéressante encore est l'analyse tracéologique menée sur ces artefacts. Ils semblent utilisés selon un mouvement caractérisé par une action dynamique rapide et assez puissante, comme l'écrasage, le martèlement, le piquetage ou le broyage. Les matériaux travaillés correspondraient essentiellement à de la matière dure animale. Le spectre des modalités d'utilisation de ces outils pourrait être un peu plus varié à Vaux-et-Borset que sur les sites mésolithiques.

Il s'agit ici d'une étude qu'il faudra bien évidemment poursuivre et enrichir à l'avenir afin de mieux comprendre le mode d'utilisation de ces outils et affiner alors les comparaisons entre les différentes communautés qui utilisent cet outillage nouveau. Cependant, on peut incontestablement lier cette innovation en contexte Swifterbant aux contacts entretenus avec les populations néolithiques de Moyenne Belgique. Ces dynamiques sont discutées à la lumière des récents résultats obtenus sur les processus de néolithisation du bassin de l'Escaut en Flandres orientales.

Mots-clés : outil facetté, nord-ouest Belgique, contact Mésolithique/Néolithique, tracéologie, industrie lithique.

13-2022, tome 119, 4, p.579-604 - Eugénie Gauvrit Roux, Jean-Marc Pétillon — Design et économie des armes de chasse magdaléniennesde la grotte Tastet (Pyrénées-Atlantiques), de la Marche (Vienne) et de la grotte Blanchard (Indre)

Design et économie des armes de chasse magdaléniennes de la grotte Tastet (Pyrénées-Atlantiques), de la Marche (Vienne) et de la grotte Blanchard (Indre)

d'Eugénie Gauvrit Roux, Jean-Marc Pétillon

Résumé : L'équipement cynégétique tient un rôle essentiel dans les économies des chasseurs-cueilleurs largement basées sur l'exploitation des ressources animales, c'est pourquoi l'identification de cet équipement, la restitution de son design et de sa gestion sont riches d'informations sur les dynamiques de ce type de société du Paléolithique à nos jours. L'analyse fonctionnelle détaillée de plusieurs séries de microlithes du Magdalénien moyen (19.5-16 cal ka BP) issues de la grotte Tastet, de la grotte Blanchard et de la grotte de la Marche, et la comparaison avec les données disponibles sur les pointes osseuses, permettent de discuter l'économie de l'armement de chasse et de proposer une restitution du design des projectiles pour les ensembles archéologiques considérés. La comparaison de la fréquence et de la spécificité des stigmates d'impact sur les microlithes montre leur grande homogénéité à l'échelle intra-site, en revanche, à l'échelle inter-sites, il existe des différences d'endommagement significatives pouvant être liées à des montages différents sur les pointes osseuses. Ces données croisées des industries lithiques et osseuses dédiées à la chasse participent à renouveler notre approche des traditions du Magdalénien moyen en affinant notre perception des rythmes complexes de changements techniques parmi les sociétés tardiglaciaires de l'Ouest de la France.

Mots-clés : Magdalénien, Tardiglaciaire, industrie lithique, industrie osseuse, analyse fonctionnelle, technologie des projectiles, ressource animale, techno-économie.

Abstract: In environments poor in vegetal resources, the acquisition of the hunter-gatherers??? alimentary and technical resources largely rests upon the success of the hunting activity; this activity thus possesses a structuring role in their techno-economic organisation. Identifying the hunting weaponry, understanding its design and its management is therefore particularly informative on the dynamics of the Palaeolithic societies, whose economies were likely mostly based on the exploitation of animal resources. This reflection is based on the detailed functional analysis of several large assemblages of microliths from the Middle Magdalenian (19.5-16 cal ka BP) of Tastet cave, Blanchard cave, and La Marche, and on a comparison with the available data on antler points from these sites. This comparative approach allows an in-depth reflection on the hunting weaponry for a period of the recent Palaeolithic marked by regional variations of certain productions and hunting purposes: the Early Middle Magdalenian (EMM; 19-17.5 cal ka BP) and the Late Middle Magdalenian (LMM; 18-16 cal ka BP) are characterised by the regionalisation of certain types of microliths and osseous projectile points, species of ungulates hunted, as well as art and ornament productions; these elements allow recognising several technical traditions in France and northern Spain. The archaeological assemblages considered here illustrate one part of the diversity of this period, as they are associated with distinct traditions and yield different morphologies of microliths and osseous points???two categories of artefacts often associated with the hunting activity, and which may have been used together as composite projectiles. La Marche is at the heart of the definition of the EMM tradition ???with Lussac-Angles points??? (notably characterised by the production of eponymous short, single-bevelled, slotted points and truncated backed bladelets), Blanchard cave is emblematic of the EMM traditions 'with navettes' (notably characterised by long, double-bevelled, slotted points, and truncated backed bladelets), and Tastet cave is associated with the LMM tradition with scalene triangles of the northern slope of the Pyrenees, and yields non-slotted, single-bevelled points.

Results allow discussing the economy of hunting weapons, offering hypothesis regarding the weapons??? design, and the potential reasons of design variations. The functional analysis shows that the use-wears on microliths and on certain osseous points are due to the impact and indicate the use of the microliths as projectile inserts: at La Marche, 34% of the 181 analysed microliths have a diagnostic impact fracture, 32% have lateral impact scars and 0.5% have linear impact traces. At Blanchard cave (layers B2-B6), 51% of the 173 analysed microliths have a diagnostic impact fracture, 35% have lateral impact scars, and 0.6% have a linear impact trace. At Tastet cave, where the sampling strategy is not based on the functional potential (as it is in the two previous sites) but includes most microliths excavated between 2013 and 2018, the frequency of damage is closer to the experimental patterns: 2% of the 126 microliths analysed in stratigraphic units 206a and 306 have an impact fracture, and 11% show lateral impact scars. Data from the microliths and projectile points analysis indicate that the projectiles were brought back to the sites after the hunting episodes, and that the damaged lithic or osseous inserts were then replaced if necessary. The accumulation of damaged lithic inserts and of osseous points indicate that these repairing sessions were recurrent. The high standardisation of osseous points (e.g., morphotype of Lussac-Angles, of la Garenne, of the north slope of the Pyrenees), and of microliths (e.g., truncated backed bladelet, scalene triangle), must have allowed the different components of composite projectiles to be interchangeable.

The analysis of the orientation, location, and frequency of impact damages on lithic inserts and their comparison to experimental data suggest that microliths from the three archaeological assemblages were likely positioned laterally (i.e., insert distant from the penetrating point of the projectile) or disto-laterally (i.e., insert in direct proximity to the penetrating point) rather than axially (i.e., insert positioned as projectile point). The comparison of the specificities of the impact damage shows their high homogeneity among the different morphotechnic categories of microliths (i.e., longitudinal cutting edge, monopoint, double-point, non-slashing rectangle) at the intra-site scale. There are however substantial differences at the inter-sites level regarding the specificities of impact fractures: bending initiated fractures and burin-like fractures are the most numerous fracture types at La Marche, bending initiated fractures dominate the small set of impact fractures at Tastet cave, whereas spin-off fractures are by far the most numerous ones at Blanchard cave. These differences refer to distinct modalities of application of impact forces, and at this stage of the methodological developments, the hypothesis of variations of propulsion type cannot be verified. Without ruling out this possibility, we suggest that the differences of impact damage are rather correlated to a combination between the differences of projectile point morphologies and different hafting modalities of lithic inserts: the short single-bevelled points of Lussac-Angles have a groove shaped on one or both sides and the length of these grooves corresponds to the average length of the microliths of La Marche, suggesting that lithic inserts were generally isolated on a face of these points. The points from Blanchard cave are longer and the groove on their side are deeper and longer, and several juxtaposed lithic inserts can potentially be inserted in them. This hypothesis is consistent with the predominance of spin-off fractures on microliths, which can be due to the constraints of the axial hafting or, more likely here, to the juxtaposition of lateral or disto-lateral lithic inserts. The size of the single-bevelled points of Tastet cave is intermediary between the two other sites, and their calibre is closer to the Lussac-Angles points. The absence of lateral grooves may refer to a multitude of hafting modalities of lithic inserts, and at this point it is not possible to precisely define how inserts were hafted.

These inter-sites differences in projectile designs can be due to multiple factors, including environmental ones (e.g., vegetal cover, climate, season, game type and availability), the efficiency sought from the projectiles (e.g., in terms of penetration depth or width of the slashed wound), or technical styles (e.g., related to cultural identities or technical transfers). Our data underline that the regional and chronological diversity of the Magdalenian is expressed in many fields, and among those fields, the variations of the hunting weaponry is particularly important as it has a key role in the economies of hunter-gatherer societies during the Palaeolithic. The joint approach of the lithic and osseous industries dedicated to the hunting activity thus participates in renewing the understanding of the complex rhythms of technical change among the Late Glacial societies of western France.

Keywords: Magdalenian, Late Glacial, lithic industry, osseous industry, functional analysis, projectile technology, animal resources, techno-economy.

12-2022, tome 119, 3, p.501-525 - Jambon A., Gomez de Soto J., Dumont L., Kerouanton I. (2022) – Les premiers fers pendant l’âge du Bronze en France : données nouvelles

Les premiers fers pendant l'âge du Bronze en France : Données nouvelles de Albert Jambon, José Gomez de Soto, Léonard Dumont, Isabelle Kerouanton

Résumé : L'analyse du fer de la goupille insérée dans la hache du Bronze moyen médocain d'Ygos-Saint-Saturnin (Landes) et l'examen physique de celle-ci révèlent que ce rivet, présenté jusque-là pour être l'élément en fer le plus ancien en France, n'est en réalité qu'une intrusion moderne, ce que confirme d'ailleurs la vérification de la bibliographie princeps de cette hache.

Ce nouvel élément chronologique d'importance a amené à reprendre les données anciennes concernant ces premiers objets en fer, en les couplant à des analyses pour certains d'entre eux, et un inventaire critique réactualisé des premiers fers attestés pendant l'âge du Bronze a été dressé : on notera en particulier qu'une pièce aussi emblématique que l'épée à poignée de bronze et lame de fer dite de Gué de Velluire en Vendée s'est révélée le résultat du remontage moderne d'une lame de l'âge du Fer sur une poignée du Bronze final.

En l'état des connaissances, en France le fer n'est connu qu'à la fin de l'âge du Bronze, possiblement dès le xiiie s. av. J.-C. (Bronze final I /Bz D), mais essentiellement au ixe s. av. J.-C. (Bronze final IIIb / Bronze final atlantique 3 /Bz B2-3). Le fer métallurgique n'est attesté que lors de cette ultime étape du Bronze final. Vingt-deux occurrences d'objets en fer ont pu être référencées, dont trois pour les étapes ancienne et moyenne du Bronze final, dix-neuf pour son étape finale. A l'exception du grand couteau de la tombe du tumulus Géraud de Saint-Romain-de-Jalionas, il s'agit de pièces de modestes dimensions, rivets, pointes de flèches du type Le Bourget, etc. On note aussi quelques épées aux poignées métalliques ornées de filets de fer.

Les objets en fer de France ne sont attestés que dans une vaste entité géographique s'étendant des lacs alpestres et de la France de l'Est à l'Atlantique, excluant le sud du pays. Une diffusion depuis l'aire balkanique de ce nouveau matériau et des techniques qui lui sont liées semble pouvoir être envisagée, bien davantage que depuis les régions de la Méditerranée où le fer ne paraît pas se diffuser avant le dernier quart du viiie s. av. J.-C. en Provence et Languedoc.

Mots-clés : Fer, âge du Bronze final, falsification, France médiane.

Abstract: If iron was used in Asia Minor from the 3rd millennium BC, it was not known in Western Europe until the 13th century BC. In France, its first appears towards the end of the Bronze Age, possibly during the 13th century BC (Bronze final I / Bz D). Iron has been subsequently documented, especially during the 9th century BC (Bronze final IIIb / Late Atlantic Bronze Age 3 / Bz B2-3). Metallurgic iron is known only during this last stage of Late Bronze Age.

The inventory of objects found in France, drawn up in 1981 and revised in 2009 has not changed much, despite several recent studies. However renewed data, with new discoveries and some objects removed from the list, call for an updated overview.

The analysis of the iron rivet inserted in the Medoc Middle Bronze Age axe from Ygos-Saint-Saturnin (Landes) revealed that this rivet, presented until then as the oldest iron element in France, is nothing more than a modern addition, confirmed when the first publications of the axe were verified.

This important new chronological element leads us to review former data of these first iron objects, to analyse several of them and to review the previous inventory of the first iron artefacts produced during the Bronze Age. We underline that the emblematic sword with a bronze hilt and an iron blade known as from Le Gué de Velluire (Vendée) is actually a forgery. It is in fact a modern reassembly of an Iron Age blade on a Late Bronze Age hilt. Twenty-two discoveries of iron objects are listed, bringing together around forty iron objects in total.

For the early and middle stages of Late Bronze Age, we have retained a bronze collared pin with its head mounted on an iron shaft found in the Saône river, two small iron rings and an "object of the same metal" found in the Champigny tomb in the Aube, as well as two iron pins on a spearhead found in the riverbed of the Moselle.

Iron is more common in the later stage of the Late Bronze Age and is found as small or medium-sized objects. The inventory includes ten arrowheads of the Le Bourget type, known in Saône-et-Loire and Côte-d'Or as well as in Vienne and Charente, five pins (including four in the Bourget Lake, and the fifth, with an iron shaft and bronze head from a hoard in Oise) and two bracelets (the Bourget Lake and Côte-d'Or). We have listed at least two iron knives: one from the Géraud tumulus in Saint-Romain-de-Jalionas (Isère) and one or two with a wide blade from the Quéroy cave in Chazelles (Charente). Various small objects, whose nature and function cannot always be determined, as well as a few rings and rivets are also known in Côte-d'Or, Seine-et-Marne, Cher, Indre, Vendée and Charente. Four iron slags were found in Loiret, but their dating remains uncertain and needs to be clarified by additional analyses. Finally, three swords with bronze hilts, from Jura, Savoie and Drôme, are decorated on the guard, the grip and the pommel with inlayed iron stripes. Conversely, the iron knife from the Géraud tumulus is mostly composed of iron and adorned with bronze inlays.

The three artefacts dating before the Late Bronze Age IIIb all come from eastern France, two of them from rivers and the third from a burial. During the Late Bronze Age IIIb, iron objects come from a broad area including the Alpine lakes and eastern France and extending to the Atlantic coastline, excluding the south of the country. A diffusion from the Balkan area of this new material and the techniques related to it seems possible, rather than from the Mediterranean, in Provence and Languedoc, where iron does not seem to spread before the last quarter of the 8th century BC. It is only much later, during the Iron Age that this new metal becomes popular and supersedes copper alloys.

Keywords: Iron, Late Bronze Age, forgery, Median France.

11-2022, tome 119, 3, p.449-499 - Couderc F. (2022) – Genèse des premières sociétés de l'âge du Bronze en Basse-Auvergne (Puy-de-Dôme, France)

Genèse des premières sociétés de l'âge du Bronze en Basse-Auvergne (Puy-de-Dôme, France) de Florian Couderc

Résumé : Le bassin de Clermont-Ferrand, en bordure de la plaine marécageuse de la Limagne d'Auvergne, regroupe la plus forte densité d'habitats et de nécropoles du Bronze ancien en France, voire au-delà. Ces habitats ont des caractéristiques tout à fait hors normes. Les habitats concentrent dans plusieurs cas quelques centaines, voire milliers de structures, essentiellement des fosses et des silos, répartis sur des surfaces atteignant parfois près de 10 ha. Le mobilier qui est retrouvé sur ces sites est tout aussi foisonnant et fournit aujourd'hui un excellent corpus de référence particulièrement abondant. Les nécropoles sont généralement associées à ces habitats. Elles sont monumentales, avec des enclos fossoyés oblongs ou circulaires, regroupant plusieurs dizaines de tombes à inhumation, majoritairement individuelles. Certaines sont accompagnées d'un mobilier prestigieux (parure en coquillage, céramique, mobilier métallique), témoignant du développement d'une élite sociale à cette période et marquant un véritable basculement par rapport à la fin du Néolithique. La question qui se pose aujourd'hui est de savoir ce qui a amené à un tel développement des sociétés du Bronze ancien dans cette microrégion située au coeur du Massif Central plus qu'ailleurs. Une analyse globale des sites, ainsi qu'une approche des territoires et de leur évolution, permettent d'entrevoir une structure territoriale multipolaire au cours de la deuxième phase du Bronze ancien (env. 1900-1750 av. J.-C.). Si une forte hiérarchisation sociale est perceptible au travers de l'étude des nécropoles, il apparaît au contraire, qu'une forme de complémentarité, voire de partage du territoire était effective durant cette phase du Bronze ancien dans le bassin de Clermont-Ferrand. Aussi, la proximité avec la plaine marécageuse de la Limagne apparaît comme l'un des critères principaux de l'implantation des sites du Bronze ancien. En parallèle, l'apparition de petits habitats situés en périphérie de ces pôles démontre une forme de conquête de nouveaux espaces durant le Bronze ancien 2. Ainsi, l'étude des sites et des territoires du Bronze ancien permet de restituer des dynamiques de gestion de l'espace sur le temps long, mais aussi d'aborder la question de la structure sociale et économique de ces sociétés agropastorales.

Mots-clés : Bronze ancien, Auvergne, habitats, nécropoles, paysages, SIG, structure sociale.

Abstract: Many Early Bronze Age discoveries (2200-1600 av. J.-C.) have been made in the Clermont-Ferrand region, on the border of the Grande Limagne (Auvergne, central France) since the 1980s. Gilles Loison one of rescue archaeology's main inventors discovered sites that remain reference points for the Early Bronze Age in France ("Machal" at Dallet in particular). The Clermont-Ferrand area has a diverse array of sites, with both domestic and funerary contexts represented. The development of commercial archaeology in the 2000s has led to the unearthing of important new sites: "Petit Beaulieu" in Clermont-Ferrand, "La Fontanille" in Lempdes and the burial site of "Chantemerle" in Gerzat. With these discoveries, the Lower-Auvergne has highest concentration of Early Bronze Age remains in France and even further afield. Data accumulated over the last 40 years has the potential of shedding new light on the organisation of territories and society from the Early Bronze Age, however research taking into account the entire Clermont-Ferrand basin has not been undertaken until now. This article aims to present the main results of a recent thesis from the University of Toulouse 2 Jean Jaurès.

Early Bronze Age settlements in the Limagne are characterised by the omnipresence of pits and grain storage pits, and by the scarcity of identifiable building plans, which differentiates them from later settlements. From the analysis of their feature density and surface area, it is possible to identify three distinct groups. Group A comprises settlements with a high density of features (several hundred to several thousand), sometimes spread over an area of almost 10 hectares. They generally occupy the edges of the Grande Limagne marshlands and are usually associated with a burial site. Group B has a lower density and smaller surface area and is not necessarily associated with a burial site. Finally, Group C comprises settlements characterised by a few erratic features spread over large areas. Both Group B and Group C settlements occupy Group A peripheral areas. An interesting fact for the regional Early Bronze Age is the extreme proximity between the world of the living and the world of the dead. In fact, these two spaces exist side by side and function in sync. The burial sites are made up of graves, generally individual, sometimes associated with circular or oblong enclosures as at the Chantemerle site. In 10% of cases, the graves contain grave goods, primarily ceramic, but also shell finery and, more rarely, metal objects (daggers, pins, and awls). These burial sites only group together a tiny part of the population, which would indicate that they are reserved for a high social stratum of the population.

An analysis of the rhythms of occupation of the burial grounds and the main settlements of Group A demonstrates their complexity. The compilation of radiocarbon dates highlights a progressive development of settlements and funerary spaces from 2100 BC onwards, reaching a peak in the region during the 1900-1750 BC interval. It is during this period that the Early Bronze Age reached its peak, with a multiplication of the graves found on the burial sites, the maximum expansion of the large Group A settlements, as well as the development of small domestic occupations in spaces rarely occupied by the previous populations. It is from about 1700 BC that this dynamic will gradually change. Some large settlements were abandoned, such as "Petit Beaulieu", while others sometimes lasted until the beginning of the Middle Bronze Age 1 (around 1600 BC). The same is true for the burial sites, of which only a few graves are dated to the 1750-1500 BC interval. The changes that mark the arrival of the Middle Bronze Age can be linked to several factors. The main one is certainly the climatic deterioration that affected the whole of Europe from the beginning of the Middle Bronze Age. The resources offered by the marshlands may have become less accessible, requiring a reorientation of agro pastoral strategies. However, we do not observe a sudden change, but a slow evolution that is certainly also linked to a breakdown of the social and territorial structure of the region.

An analysis of the territories and inter-site relationships has revealed a high degree of proximity between the main settlements (Group A) that border the Grande Limagne. Sometimes less than an hour's walk was needed to connect one site to another. Areas available without the close proximity of a neighbouring site were therefore very limited, and the populations certainly had to maintain day to day relationships. In this context, a form of competitiveness between communities is unlikely. In reality, given the layout of the territorial network, it is probably a form of sharing of activities or functions between human groups that was in use during the Early Bronze Age. Clearly, the economy of these societies was essentially based on cereal cultivation and animal husbandry (mainly cattle). The production of surpluses certainly allowed part of the population to accumulate wealth and enter into an economy of surplus management, allowing the emergence of a social elite. Contrary to the schema usually proposed of a hierarchical and centralised society for protohistoric periods, it seems more likely that we are faced with a heterarchical society, with decentralised social distinction, Indeed, the presence of burial sites within each of the Group A settlements demonstrates that each site had its own small elite community. However, we have seen that these sites are too close to each other to have dominating or conflicting relationships. We therefore believe that during the Early Bronze Age in the Lower Auvergne, each of the large settlements had its own socio-political organisation, but they cooperated in the management and development of the territory. This situation is essentially valid for the interval 1900-1750 BC and it is probably different for earlier and later periods.

The Clermont-Ferrand Basin finally constitutes an excellent laboratory for the study of Early Bronze Age societies and territories in Western Europe. The mass of data available to date is particularly important and requires a cross-cutting approach in order to respond to the various problematics. The volume of material collected and the large amount of information will require many more years of research.

Keywords: Early Bronze Age, Auvergne, settlement, funerary landscape, landscape archaeology, GIS, social anthropology.

10-2022, tome 119, 3, p.421-447 - Paillet P., Paillet E. (2022) – « Le seul réel dans l’art, c’est l’art » : réalisme, naturalisme et illusionnisme des oeuvres d’art paléolithique

« Le seul réel dans l'art, c'est l'art »* Réalisme, naturalisme et illusionnisme des Oeuvres d'art paléolithique de Patrick Paillet, Elena Paillet

Résumé : Investir le champ des images préhistoriques n'est pas un acte anodin. L'objet artistique est un puissant marqueur social et culturel. Il révèle des aspects particulièrement intimes des sociétés qui l'ont produit et peut servir le cas échéant à éclairer les mouvements qui les traversent, à évaluer la nature des échanges socio-culturels, à mesurer la qualité des partages de valeurs symboliques et à pister les relations entre groupe ou communauté au sein même de territoires physiques et de territoires symboliques qu'ils servent à baliser dans différentes dimensions. Les images reflètent une manière d'instruire en rendant visible le monde qui diffère de son exploitation induite par la culture matérielle. Les productions symboliques constituent donc une voie privilégiée vers la perception et la représentation du monde. Les négliger serait se priver de leur dimension idéologique ou de leurs intentions conceptuelles qui font parfois défaut aux classifications basées sur la seule variabilité typo-technologique des systèmes techniques (Fortea Perez et al., 2004). Encore que tous les systèmes ou les productions techniques ne soient pas toujours dépourvus de valeur esthétique et donc peut-être symbolique (Beaune et Hilaire-Pérez, 2012). Mais une fois acquise la conviction que l'oeuvre d'art est fondamentale comme matière à penser et comprendre les sociétés de la Préhistoire, on ne peut pas s'exonérer d'une réflexion sur sa forme, notamment dans le champ figuratif, et sur la manière dont elle traduit ou interprète la vie. L'objectivité des images est ainsi questionnée. Leur degré de fidélité au réel, souvent labellisé par les termes assez ambigus de « réalistes » ou « naturalistes », est également analysé sous l'angle d'une sémantique qui autorise le passage de l'étroit corridor entre images naturelles, images mentales et images artificielles. Loin d'une stérile guerre sémantique, cette nouvelle lecture donne à voir autrement l'iconographie préhistorique.

Mots-clés : art, Préhistoire, réalisme, naturalisme, illusionnisme, représentation, iconographie.

Abstract: Alongside stone and bone industries and remains of hunted and consumed animals, the images placed on objects or walls constitute a gateway into the economic, social, cultural, ideological and symbolic heart of prehistoric societies. It is then necessary to study them, as these images are also a reflection of a visible world and, at the same time, of a vision of the world worth to teach. Prehistoric artists have borrowed from living world, especially animals and humans (very rare plant representations), a large part of their themes, even if abstract or geometric symbols, which are called signs, and some of which probably have figurative origin (objects, living beings, etc.), constitute an iconographic background. But signs, as fascinating as they are to study, are products of the pure imagination and the ideal over which we have little authority because they escape nature. Then to reassure us on our capacity to decipher this world of the images, we often approach it by the outside, i.e. by form, matter, technique or style. And it is the figurative representations that lend themselves best to this exercise. Don't we often say that prehistoric art is an animal art? It is a shortcut, but also a clever way to put aside the signs that resist us. Prehistoric man, as early as the Aurignacian period, excelled in the art of representing animals, at the same time as they hunted, trapped and consumed them. The symbolic and the hunting, the bestiary and the fauna, constitute the two poles of opposite appearance - but finally similar - of a network of complex relations between the man and the animal. The bestiary is not a reasoned and exhaustive inventory of living things. It is a symbolic selection, a cultural and allegorical vision. Prehistoric artists did not draw up a natural and zoological history of the wild animals they encountered, now extinct or emigrated, and even less a manual of anatomy, ethology or animal biology. It is obvious and the simple observation of animal images would be enough to convince us. However, we still practice this exercise of more or less literal reading of the representations, because we seek at all costs, by idealizing and exalting the supposed figurative realism of the painted and engraved animals of Prehistory, to take the prehistoric out of the primitive state in which it is sometimes locked up. But by practicing this, by dissecting images in order to describe their fidelity or perfection, we neglects the innumerable departures from the art of imitation, from reality quite simply. If prehistoric art can occasionally achieve a synthesis between the vision of the hunter, the one who knows how to see, and the hand of the artist, the one who knows how to express, we should not make a doctrine of it. Between eye and hand, there is a brain in which experience and imagination mix and feed each other. Whatever the words we frequently use to describe prehistoric animal art, "realist" or "naturalist", words that seem close but can also be contrary, they take us away from reality since mimetic accuracy has never been an objective. And how could it be so, since everyone has his own perception and his own interpretation of reality. Everyone sees the visible world and bears witness to it in his own way. The images of prehistory, and more particularly those of animals, are the manifestations of these multiple and subjective visions of the world of an individual nature, as the product of an interior glance, and social, as the product of the outside, visions more or less accommodated to collective constraints. As in the Middle Ages, the true nature of the animals during the Prehistory, the nature that the artists allot to them, resides more in the ideal nor the metaphysical, the true in some way, than in the scrupulous observation of the living, the reality.

Keywords: art, Prehistory, realism, naturalism, illusionism, representation, iconography.

09-2022, tome 119, 3, p.379-420 - Nicoud E., Aureli D., Pagli M., Villa V., Tomasso A., Pereira A., Nomade S., Lemorini C., Zupancich A., Nunziante Cesaro S. (2022) – Techno-economic behaviours during Middle Pleistocene: Valle Giumentina level ALB-42 (MIS

Nicoud E., Aureli D., Pagli M., Villa V., Tomasso A., Pereira A., Nomade S., Lemorini C., Zupancich A., Nunziante Cesaro S. (2022) - Techno-economic behaviours during Middle Pleistocene: Valle Giumentina level ALB-42 (MIS 12b, Abbateggio, Central Italy)

Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française, 119, 3, p. 379-420.

Abstract: The recent excavation of level ALB-42 of Valle Giumentina open air site (Italy) has yielded 407 lithic artefacts and some Red Deer bone fragments, showing anthropic marks. Lithic refits appear in this clayey-silty paleosol developed during an interstadial phase, assigned to MIS 12b (c. 450 ka) according to sedimentary studies and radiometric dating (40Ar/39Ar and ESR-U/Th). Here we present taphonomic and spatial studies and a techno-economic approach including archeozoology, petrography, technology and use-wear analysis on artefacts. Good quality cherts were selected mainly from the immediate surroundings. They were brought into the site as small blocks or big flakes. Tool making or retouching are sometimes made on the spot. Tools are used for wood processing and butchery during brief but recurrent activities. A techno-morphological diversity of lithic products appears leading us to discuss intra- and extra- site diversity within the Lower Paleolithic of Italy and MIS 12 settlements in Europe.

Keywords: Middle Pleistocene, Lower Paleolithic, Acheulian, techno-economy, petrography, technology, sedimentology, taphonomy, MIS 12.

Résumé : La diversité typo-technique des industries lithiques du Paléolithique inférieur européen est avérée mais nul ne saurait encore l'expliquer en termes fonctionnels et techno-économiques. La rareté des sites, en particulier en période glaciaire, leur qualité de conservation variable et une faible résolution chronologique et paléoenvironnementale des occupations constituent un autre verrou majeur à la connaissance du peuplement humain au Pléistocène moyen.

Aussi avons-nous ouvert de nouvelles fenêtres stratigraphiques sur le site en plein air de Valle Giumentina, objet de fouilles dans les années 1950 par A.M. Radmilli. Situé dans le massif calcaire riche en silex de la Maiella (Abruzzes, Italie centrale), c'est un bassin d'1 km² désormais suspendu à 740 m d'altitude, empli de sédiments sur près de 45 m d'épaisseur en son centre. Une incision récente profonde de 25 m offre l'accès aux dépôts lacustres, palustres, glaciaires et aux paléosols interstratifiés contenant 11 niveaux archéologiques. Cette exceptionnelle séquence sédimentaire s'est mise en place entre les MIS 15 et 12, et les occupations humaines peuvent être datées entre 585 ka et 450 ka environ (Nicoud et al., 2016a ; Villa et al., 2016a, 2016b).

Une aire de 55 m² a été fouillée de 2012 à 2015 dans le niveau archéologique supérieur in situ nommé ALB-42. Cette couche d'argiles limoneuses brunes à structure prismatique comporte des sables calcaires et des graviers de silex, des fragments de verres volcaniques fortement altérés et des minéraux volcaniques épars, d'origine détritique. L'horizon pédologique est très homogène avec des traits de bioturbation et d'assèchements et gonflements des argiles. ALB-42 correspond à une phase climatique tempérée et humide pendant une période glaciaire, permettant le développement de ce sol mature à fortes caractéristiques hydromorphes. Une nouvelle datation exposée ici (454.5 ± 5.0 ka, méthode 40Ar/39Ar), cohérente avec une datation ESR-U/Th sur dent de Cerf du même niveau archéologique, attribue ALB-42 au MIS 12. Les données sédimentologiques et paléoenvironnementales affinent cette attribution et le corrèlent à l'interstadiaire MIS 12b.

Quatre cent sept pièces lithiques sont apparues ainsi que 55 fragments d'os de Cerf dont certains présentent des traces anthropiques. 12 unités de remontages lithiques, bien circonscrites dans l'espace, regroupent un total de 52 pièces. Les surfaces souffrent peu d'altérations mécaniques. Un aspect brillant et une légère patine blanche sont présents sur la plupart des pièces, ce qui est cohérent avec un sol hydromorphe en milieu argileux. L'évaluation taphonomique atteste ainsi d'une cohérence de l'assemblage archéologique suffisante pour mener une étude techno-économique, fondée sur l'étude des chaînes opératoires de production lithique.

L'étude pétrographique décrit notamment les deux grandes familles de silex de la Maiella qui constituent la quasi-totalité du mobilier, réparti en une quinzaine d'unité de matières premières (RMU). Des silex de très bonne qualité ont été sélectionnés dans un conglomérat voisin et apportés sur le site sous forme de petits blocs ou de gros éclats, voire d'outils finis, ne dépassant jamais 15 cm de long et pesant au maximum 800 g. Un stock de silex d'origine plus lointaine (Maiolica) est aussi importé sous forme d'éclats épais.

Le façonnage bifacial est absent. On compte 5 nucléus stricto sensu. Le débitage relève d'un même concept de taille exploitant un ou plusieurs sous-volumes du nucléus selon plusieurs méthodes sans préparation des surfaces et par percussion directe interne à la pierre dure. Parfois, un RMU montre une production récurrente d'un morphotype d'éclat et/

ou de tranchant mais, en général, le débitage fournit un large panel de supports. Les éclats à dos sont rares. Une caractéristique

majeure de la série est la présence d'éclats épais, dont la fonction est questionnable : outils et/ou nucléus ? Parfois, la présence d'une retouche régularise le tranchant de la pièce-outil mais les nucléus ne sauraient être ici les seuls pourvoyeurs des nombreux éclats. On compte 38 éclats retouchés. La retouche est toujours directe, mais les tranchants réalisés varient fortement dans leur délinéation ou leur angle. Typologiquement, les outils sont des racloirs latéraux, des denticulés, et une pièce porte un museau. La convergence de deux segments du tranchant peut créer une pointe robuste. 26 pièces portent des traces d'utilisation peu marquées, en raison d'un emploi sur des matériaux tendres et/ou une utilisation brève. Le travail du bois est aussi attesté (raclage).

Valle Giumentina ALB-42 apparaît comme un site occupé de manière récurrente pendant le MIS 12b et dédié à des activités spécifiques au sein d'un territoire. Des activités de boucherie ont pu être reconnues. L'image d'une présence pérenne des populations dans les environs du site émerge, renforcée par les nombreux niveaux d'occupation du site, aussi bien en période glaciaire qu'interglaciaire. Le site nous amène à nous interroger sur les éléments de continuité plutôt que de changements, en particulier techno-économiques, au cours des 135 000 ans enregistrés dans la séquence. ALB-42 présente une industrie originale dans le panorama du Paléolithique inférieur italien peut-être liée à un contexte pétrographique caractérisé par une matière première abondante et de qualité. Des comparaisons sont menées avec cinq sites européens attribués au MIS 12, dont les contextes sont précisés ici, sans que des ressemblances typo-techniques n'apparaissent clairement. Toutefois, l'utilisation de matières premières locales est la norme tout comme l???absence de préparation des nucléus. Les outils retouchés ou non, sont de morphologie très variée.

Pour être affinée, notre connaissance des sociétés du Paléolithique inférieur requiert aujourd'hui une multiplication de données issues de sites dont la datation peut être précisée par un croisement d'indices jusqu'au sous-stade isotopique, et la cohérence des vestiges, avérée par l'analyse taphonomique. Quatre autres niveaux bien préservés ont été fouillés récemment à Valle Giumentina (du MIS 13b au MIS 12b). Ils viendront abonder cette accumulation nécessaire.

Mots-clés : Pléistocène moyen, Paléolithique inférieur, Acheuléen, technologie, techno-économie, pétrographie, sédimentologie,

taphonomie, MIS 12.

07-2022, tome 119, 2, p.259-294 – Sicard S., Barbier-Pain D., Brisotto V., Dietsch-Sellami M.-F., Hamon G., Vissac C. (2022) – Biographie d’un monument mégalithique du Néolithique moyen sur la côte sauvage de Quiberon dans le Morbiha -

Biographie d'un monument mégalithique du Néolithique moyen sur la côte sauvage de Quiberon dans le Morbihan

Sandra Sicard, Delphine Barbier-Pain, Vérane Brisotto,Marie-France Dietsch-Sellami, Gwenaëlle Hamon, Carole Vissac

Résumé : Plusieurs opérations d'archéologie préventive réalisées entre 2016 et 2019, dans le village du Manémeur sur la côte Sauvage de Quiberon, ont conduit à la (re)découverte des derniers vestiges d'un ensemble mégalithique néolithique dont l'état de dégradation très avancé a fait disparaître la quasi-totalité de l'élévation. Malgré cela, la fouille a constitué une opportunité unique sur le littoral morbihannais d'étudier les structures de base et les fondations d'un monument de ce type, mettant en évidence des cloisonnements internes au cairn et des niveaux de préparation destinés à recevoir les dallages des espaces internes.

Il s'agit d'un cairn incluant deux dolmens à chambres quadrangulaires et à couloirs assez longs, parallèles et s'ouvrant au sud-est. Les plans partiels des espaces sépulcraux ont pu être restitués et les niveaux de circulation identifiés grâce aux dallages des sols, mégalithique pour celui de la chambre du dolmen 1. La chambre du dolmen 2 prend appui contre le parement de la chambre du dolmen 1, impliquant l'antériorité de ce dernier.

Le substrat sous-jacent au monument mis à nu en fin de fouille a révélé des traces d'extraction de grandes dalles préalablement à l'érection de ce dernier. L'étude micromorphologique a montré que les terres qui recouvraient le substrat avaient été en grande partie remaniées, très probablement raclées pour permettre l'extraction puis réétalées avant la construction.

Le mobilier archéologique associé, assez abondant, a permis d'attribuer le dolmen 1 à la fin du Néolithique moyen II, ce que confirment les datations radiocarbone. Le dolmen 2, moins riche, a livré un mobilier plus mélangé, dont l'essentiel oriente vers une attribution au début du Néolithique récent. Exclusivement découverts sous les niveaux de sol du monument, ces mobiliers céramique et lithique ont une répartition spatiale très inégale qui ne semble pas fortuite et résulte très probablement d'une mise en scène. De la même façon, les études environnementales ont révélé la présence de plantain, Plantago lanceolata pour la carpologie et Plantago coronopus pour la palynologie, dont les très fortes concentrations plaident pour un épandage anthropique. Ces vestiges et leur disposition dans et en dehors de l'espace funéraire témoignent de dépôts associés à la fondation du monument.

Mots-clés : Néolithique moyen, mégalithisme, techniques de construction, dépôts funéraires.

Abstract: Several preventive archaeology operations carried out between 2016 and 2019, in the village of Manémeur on the wild coast of Quiberon, have brought to light the last remains of a Neolithic megalithic complex whose advanced state of degradation has caused the disappearance of almost the entire elevation. This monument was originally described as consisting of three dolmens included in a single cairn, arranged on the same line running from north to south. Before our intervention, it had already been the subject of several investigations at the end of the 19th century and in the 1930s.

In spite of this, the exhaustive excavation has revealed the modes and phases of construction of this complex monument, built in several stages.

It is a cairn including two dolmens with quadrangular chambers and fairly long passages. They are parallel and open to the southeast. The partial plans of the sepulchral spaces could be reconstructed thanks to the presence of either the remains of broken granite standing stones, or the pits where the torn off elements were wedged in place, or, in dolmen 2, the intact orthostats. The circulation levels in these spaces were identified thanks to the paving of the floors, megalithic for that of the chamber of dolmen 1. The excavation revealed the relative chronology of the main construction phases of dolmen 1. The two parts of the corridor have sufficiently different characteristics to suppose that they were built in two phases, with a first northern portion extended by a southern portion, and are part of successive architectural projects. The chamber of dolmen 2 rests against the facing of the chamber of dolmen 1, implying that the latter was built earlier. The excavation was a unique opportunity on the Morbihan coast to study the basic structures and foundations of a monument of this type, revealing the internal partitions of the cairn and the preparation levels intended to receive the paving of the internal spaces.

The cairn, as well as the facings and orthostats of the monument, is made up almost exclusively of granitic elements, even if a few blocks of quartz or pegmatite are occasionally present. If most of them have less sharp edges that indicate an extraction, the construction of the external facing is clearly distinguished from the rest by the placement of blunt blocks with rounded shapes attesting to a collection on the foreshore.

The substratum underneath the monument, exposed at the end of the excavation, revealed traces of extraction of large slabs prior to the erection of the monument. The extraction was facilitated by the flaky texture of the granite and a network of diaclases that cut the massif into parallelepipedic blocks.

At the same time, it has allowed a regularization of the terrain, inscribed on an eminence linked to a granitic rise. The micromorphological study showed that the soil covering the substratum had largely been reworked, most likely scraped to allow extraction and then respread before construction. Some large quartz impactors as well as several bevelled pieces are likely to have participated in the removal of the granite slabs.

The associated archaeological material, which is quite abundant, has made it possible to attribute dolmen 1 to the end of the Middle Neolithic II, which is confirmed by radiocarbon dating. Dolmen 2, less rich, yielded more mixed material, most of which points to an attribution to the beginning of the Late Neolithic. Exclusively discovered under the floor levels of the monument, these ceramic and lithic materials have a very uneven spatial distribution that does not seem fortuitous and is probably the result of staging. Similarly, environmental studies have indeed revealed the presence of plantain, Plantago lanceolata for carpology and Plantago coronopus for palynology, whose very high concentrations argue for an anthropic spreading. These remains and their arrangement inside and outside the funerary space thus testify to deposits associated with the foundation of the monument, which constitute practices that are rarely discussed because they are too rarely brought to light.

The Manémeur site is part of a vast group of monuments of the same type (passage graves enclosed in a terminal cairn) identified in the vicinity and more widely on the Morbihan coast. Many of them belong to the Middle Neolithic or the late Neolithic. Although some of them group up to four passage dolmens in the same cairn, the relative chronologies are not always clearly established and the internal structures of the cairns have not been explored much.

The excavation carried out here has brought new light and new knowledge to this ensemble, showing at the same time all the informative potential of the exhaustive study of such monuments, even when they have been largely destroyed.

Keywords: Middle Neolithic, megalithism, building technique, grave offering.

06-2022, tome 119, 2, p.223-257 – Allard P., Cayol N. (2022) – Industrie lithique et activités domestiques au Néolithique ancien : le Rubané de la vallée de l’Aisne

Allard P., Cayol N. (2022) - Industrie lithique et activités domestiques

au Néolithique ancien : le Rubané de la vallée de l???Aisne, Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française, 119, 2, p. 223-257.