- La SPF

- Réunions

- Le Bulletin de la SPF

- Organisation et comité de rédaction

- Comité de lecture (2020-2025)

- Ligne éditoriale et consignes BSPF

- Données supplémentaires

- Annoncer dans le Bulletin de la SPF

- Séances de la SPF (suppléments)

- Bulletin de la SPF 2025, tome 122

- Bulletin de la SPF 2024, tome 121

- Bulletin de la SPF 2023, tome 120

- Bulletin de la SPF 2022, tome 119

- Archives BSPF 1904-2021 en accès libre

- Publications

- Newsletter

- Boutique

Prix : 15,00 €TTC

11-2021, tome 118, 3, p. 453-473 - E. López-Montalvo, C. Manen, J. Guilaine, F. Baleux, F. Convertini — Figurative graphic expressions and the first Western Mediterranean farmers: a new zoomorphic contribution from Southern France

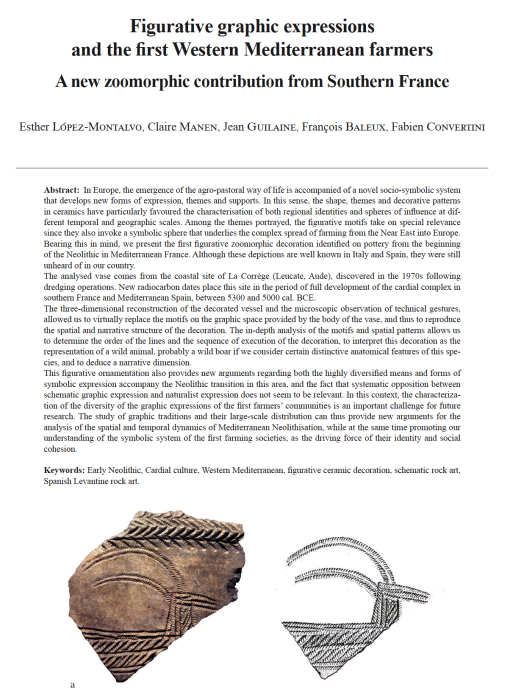

Figurative graphic expressions and the first Western Mediterranean farmers

A new zoomorphic contribution from Southern France

Esther López-Montalvo, Claire Manen, Jean Guilaine, François Baleux, Fabien Convertini

Abstract:

In Europe, the emergence of the agro-pastoral way of life is accompanied of a novel socio-symbolic system that develops new forms of expression, themes and supports. In this sense, the shape, themes and decorative patterns in ceramics have particularly favoured the characterisation of both regional identities and spheres of influence at different temporal and geographic scales. Among the themes portrayed, the figurative motifs take on special relevance since they also invoke a symbolic sphere that underlies the complex spread of farming from the Near East into Europe. Bearing this in mind, we present the first figurative zoomorphic decoration identified on pottery from the beginning of the Neolithic in Mediterranean France. Although these depictions are well known in Italy and Spain, they were still unheard of in our country.

The analysed vase comes from the coastal site of La Corrège (Leucate, Aude), discovered in the 1970s following dredging operations. New radiocarbon dates place this site in the period of full development of the cardial complex in southern France and Mediterranean Spain, between 5300 and 5000 cal. BCE.

The three-dimensional reconstruction of the decorated vessel and the microscopic observation of technical gestures, allowed us to virtually replace the motifs on the graphic space provided by the body of the vase, and thus to reproduce the spatial and narrative structure of the decoration. The in-depth analysis of the motifs and spatial patterns allows us to determine the order of the lines and the sequence of execution of the decoration, to interpret this decoration as the representation of a wild animal, probably a wild boar if we consider certain distinctive anatomical features of this species, and to deduce a narrative dimension.

This figurative ornamentation also provides new arguments regarding both the highly diversified means and forms of symbolic expression accompany the Neolithic transition in this area, and the fact that systematic opposition between schematic graphic expression and naturalist expression does not seem to be relevant. In this context, the characterization of the diversity of the graphic expressions of the first farmers' communities is an important challenge for future research. The study of graphic traditions and their large-scale distribution can thus provide new arguments for the analysis of the spatial and temporal dynamics of Mediterranean Neolithisation, while at the same time promoting our understanding of the symbolic system of the first farming societies, as the driving force of their identity and social cohesion.

Keywords: Early Neolithic, Cardial culture, Western Mediterranean, figurative ceramic decoration, schematic rock art, Spanish Levantine rock art.

Résumé :

En Europe, l'émergence du mode de vie agropastoral s'accompagne d'un changement du système socio-symbolique des sociétés qui développent de nouvelles formes d'expression graphique, de nouveaux thèmes et supports. En ce sens, la forme, les thèmes et les motifs décoratifs de la céramique ont particulièrement soutenu la caractérisation des identités régionales et des sphères d'influence néolithiques à différentes échelles temporelles et géographiques. Parmi les thèmes représentés, les motifs figuratifs revêtent une importance particulière car ils évoquent également une sphère symbolique propre aux communautés agropastorales qui diffusent depuis le Proche-Orient jusqu'en Europe occidentale, permettant ainsi d'approfondir la connaissance du cheminement des symboles identitaires dans cette vaste aire géographique.

Dans cette perspective, nous présentons le premier décor zoomorphe figuratif identifié sur une poterie du début du Néolithique en France méditerranéenne. Si ces représentations sont bien connues en Italie et en Espagne, elles étaient en effet encore inédites sur notre territoire. A ce jour, il n'est pas possible de déterminer si cette absence d'expression figurative sur les poteries est corrélée à une méthodologie biaisée (difficultés à identifier les thèmes ?), ou si elle représente une véritable lacune témoignant d'une histoire culturelle différenciée. Le vase analysé provient du gisement littoral de La Corrège (Leucate, Aude), découvert dans les années 1970 suite à des opérations de dragage. De nouvelles datations placent le gisement dans la période de plein développement du complexe cardial dans le sud de la France et en Espagne méditerranéenne, entre 5300 et 5000 cal. BCE. Parmi les éléments recueillis sur ce site, on trouve plus de 600 fragments de vases décorés selon une stylistique typique du Cardial franco-ibérique. Parmi ces fragments, trois tessons présentant un décor singulier ont été identifiés comme faisant partie du même récipient dans les premiers travaux de synthèse réalisés dans les années quatre-vingt, mais leur décor n'avait jamais fait l'objet d'une étude approfondie concernant les thèmes ou la composition des motifs. Récemment, la révision de l'assemblage céramique de La Corrège nous a permis de fournir une image plus complète de la morphologie et du décor de ce récipient en identifiant trois nouveaux tessons. Ce vase présente des caractéristiques très originales tant du point de vue de la pâte que du système décoratif qui le distinguent nettement du reste de la collection. Afin de pouvoir entreprendre une analyse exhaustive de la composition décorative du vase, nous nous sommes appuyés sur une modélisation et une reconstruction tridimensionnelle virtuelle du vase, fondée sur les caractères morphométriques des tessons conservés, ainsi que sur une observation détaillée des motifs identifiés et des techniques d'impression à l'aide d'un microscope stéréoscopique. Cette restitution 3D nous a permis de replacer virtuellement les motifs sur l'espace graphique fourni par la panse du vase, et ainsi de reproduire la structure spatiale et narrative de la décoration. L'analyse approfondie des motifs et des schémas spatiaux nous permet de déterminer l'ordre des tracés et la séquence d'exécution du décor, d'interpréter ce décor comme la figuration d'un animal sauvage, probablement un sanglier si nous considérons certains traits anatomiques distinctifs de cette espèce, et d'en déduire un sens narratif. Ce décor s'organise selon une frise horizontale, localisée à la jonction entre le col et la panse du vase, composée d'au moins 4 figurations animales opposées deux à deux.

Les caractéristiques du vase à décor figuratif de La Corrège ouvrent ainsi la discussion sur le phénomène graphique, pariétal et mobilier, qui accompagne l???émergence et l'expansion du Néolithique méditerranéen, et nous invite en même temps à nous interroger sur la valorisation de la sphère du sauvage dans le système symbolique des premières communautés agropastorales. Les parallèles formels, thématiques et techniques établis entre le vase de La Corrège et celui issu du célèbre gisement de la Cova de l'Or en Espagne, livrent de nouveaux arguments en faveur des liens existants entre les horizons cardiaux languedocien et ceux du pays Valencien. Ces expressions graphiques participent ainsi, comme les autres catégories de vestiges, à la définition des paysages culturels et des sphères d'influence des communautés néolithiques. D???une manière plus générale, on peut observer qu'il existe un fonds graphique commun aux sociétés agropastorales de Méditerranée occidentale, caractérisé par le partage de certains thèmes, notamment les anthropomorphes, ou symboles schématiques. La réalisation de décors figuratifs sur support céramique (anthropomorphes, zoomorphes et signes) est, par exemple, un mode d'expression bien connu qui accompagne l'implantation du Néolithique, bien que leur répartition sur les sites côtiers italiens, français et ibériques soit très hétérogène. On observe néanmoins, au sein de ce spectre symbolique, une hétérogénéité des moyens et des formes d???expression, comme de fortes disparités.

Cette ornementation figurative fournit également de nouveaux arguments pour relativiser l'opposition systématique faite entre l'expression graphique schématique et l'expression naturaliste. Le décor du vase de La Corrège, comme d'autres vases espagnols, montre en effet à quel point il est parfois difficile d'assigner tel caractère à telle tradition graphique et que les plages de recouvrement d'une tradition à une autre sont importantes. Dans ce contexte, la caractérisation de la diversité des expressions graphiques des premières communautés d'agriculteurs est un défi important pour la recherche future. Dans le même temps, il semble désormais intéressant d'envisager la décoration céramique sous l'angle de la production graphique. L'étude des traditions graphiques et de leur distribution à large échelle peut ainsi apporter de nouveaux arguments à l'analyse des dynamiques spatiales et temporelles de la néolithisation méditerranéenne tout en favorisant notre compréhension du système symbolique des premières sociétés paysannes, moteur de leur cohésion identitaire et sociale.

Mots-clés : Néolithique ancien, Cardial, Méditerranée occidentale, céramique, décoration figurative, art schématique, art levantin.

Autres articles de " Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française 2021"

17-2021, tome 118, 4, p. 697-737 - C. HAMON, S. REGUER, V. BRISOTTO, C. LE CARLIER DE VESLUD, K. DONNART, S. BLANCHET, Y. PAILLER, Y. ESCATS, L. BELLOT-GURLET - Des outils de métallurgistes dans le Bronze ancien de Bretagne ? Révéler l

Des outils de métallurgistes dans le Bronze ancien de Bretagne ? Révéler le rôle du macro-outillage lithique en associant analyses tracéologiques et de spectroscopie de fluorescence X

Caroline Hamon, Solenn Reguer, Vérane Brisotto, Cécile Le Carlier de Veslud,

Klet Donnart, Stéphane Blanchet, Yvan Pailler, Yoann Escats, Ludovic Bellot-Gurlet

Résumé : La question de l'émergence et du développement des métallurgies du cuivre et du bronze constitue un enjeu majeur pour aborder les dynamiques culturelles et économiques de la fin du Néolithique et du début de l'âge du Bronze dans l'Ouest de l'Europe. Pour autant, les vestiges d'activités minières comme d'ateliers de productions métallurgiques restent particulièrement indigents à l'échelle de la façade atlantique pour le Bronze ancien, en particulier dans le Massif armoricain. Cet article présente les résultats menés en combinant analyse tracéologique et analyses élémentaires par spectroscopie de fluorescence des rayons X (XRF) sur une série d'outils macrolithiques issus de cinq sites de la péninsule armoricaine. Elles mettent en évidence l'utilisation d'outils de concassage, de marteaux et d'aiguisoirs pour le travail d'objets en alliage cuivreux à toutes les étapes de la chaine opératoire de production et de transformation du métal (production, mise en forme, entretien). L'identification de différents types d'outils de métallurgistes, pour certains spécialisés, interroge sur la représentation de cette activité dans une large variété de contextes du début de l'âge du Bronze. Elle pose également la question de la segmentation des étapes de la chaîne opératoire dans le temps et l'espace, en particulier entre les zones d'extraction, la métallurgie primaire visant à la production de métal et la métallurgie secondaire dédiée à la mise en forme voire à la finition des objets. Les différents contextes d'occupation dont ces outils sont issus laissent envisager une production d'alliage cuivreux qui malgré sa discrétion dans les vestiges archéologiques, devaient sans doute être plus importante qu'initialement envisagée.

Mots-clés : métallurgie, cuivre, outillage lithique, âge du Bronze ancien, Bretagne, tracéologie, fluorescence des rayons X, spectroscopie XRF portable, rayonnement synchrotron.

Abstract: The question of the emergence and development of copper and bronze metallurgies is a major issue in addressing the cultural and economic dynamics of the late Neolithic and early Bronze Age in Western Europe. This phenomenon is particularly relevant along the Atlantic coast, where the Armorican peninsula is central for better understanding how the control of these new productions contributed to the emergence of new elites and their chiefs, notably within the Armorican Tumulus culture (2150-1750 BC).

However, evidence of Early Bronze Age mining activities and metallurgical production workshops remains scarce on the Atlantic coast, particularly in the Armorican Massif. The rare sources of copper ore are generally poor which have long suggested that the presence of metallic objects discovered in the rich burials of these periods, in particular in the tumuli of the Early Bronze Age, could only be the result of imports over more or less long distances. Recent work on the composition of some Armorican bronze objects has also highlighted a close proximity to ores from Ross Island in Ireland, suggesting that ores or ingots were imported from other regions, including across the Channel. Other works have nevertheless underlined that the exploitation of local copper veins could be envisaged in the Armorican Massif, especially as copper objects appear to concentrate in this area. Therefore, the discovery of direct or indirect evidence of copper metallurgy, particularly on settlement sites, is crucial for these periods. The presence of rare crucibles, moulds and ingots, as well as hearth structures and even furnaces, are precious clues for identifying possible episodes of metallurgical production. Stone tools constitute a second group of clues attesting metallurgical production throughout the Bronze Age, since they are now known to have been used at different stages of the operating chain, from the extraction and transformation of ores to the shaping and finishing of metal objects by hammering and abrading.

This paper presents the results of a combination of use-wear and elementary X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) analysis of a series of macrolithic tools from the Armorican Peninsula. The analyzed corpus comes from five sites in Britany dated by their pottery or by radiocarbon dating to the Early Bronze Age: it includes a settlement enclosure (Bel air, Lannion), an island settlement (Beg ar Loued, Molène) as well as less structured occupations however characteristic of the period (Kersulec, Plonéour-Lanvern; la Colignière, Trémuson; ZAC Kerisac, Plouisy). They illustrate the diversity of the contexts encountered dating to this period in the western part of the Armorican peninsula. For each of the sites, several tools were selected from a larger corpus of macrolithic tools, based on criteria of the raw materials, type of active surfaces and nature of the use-wear traces. The assemblage includes 19 macrolithic tools: 3 crushing-grinding tools, 2 tools with cupules, 1 pestle, 2 anvils, 3 hammerstones, 1 percussion or crushing tool, 3 heaps, 3 hammers and finally 2 sharpeners.

The functional analysis method is based on the combination of the results of a low and high magnification use-wear analysis and elementary X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analyses, with two implemented measurement methods: portable X-ray fluorescence spectrometer (pXRF) and X-ray fluorescence mapping under Synchrotron radiation (Sy-XRF). The use-wear analysis alone therefore made it possible to exclude metallurgical use for 3 of the 13 tools analyzed, the other 10 tools showing traces at least linked to the working of mineral materials, with three quarters of them showing a combination of traces strongly suggesting the working of ore or metal. The combination of the use-wear and XRF analyses allows us to propose a use for ore processing or the transformation of metallic materials for 8 of these 10 tools. This result underlines that the hypotheses formulated following the use-wear analysis are well supported by the elementary residue analyses. The p-XRF analysis is able to detect copper residues even in relatively small quantities and to detect the heavier elements, such as tin. An average quantification is obtained, representing an analytical area of about 3 mm. Furthermore, the analytical precision permitted by Sy-XRF analysis, thanks in particular to the elemental distribution maps, with a selected resolution of a few tens of micrometers, makes it possible to distinguish chemical elements from the minerals making up the heterogeneous rocks generally used for macro-tools from the residues of processed materials that had catched on the surface. It also shows the correlations between the elementary distributions and the areas showing the traces of use. Due to the implementation modalities, the complementarity and concordance of the results of the Sy-XRF and p-XRF analyses with regard to the detection of copper residues is therefore stressed here.

These analyses highlight the use of crushing tools, hammers and sharpeners for the working of copper alloy objects at all stages of the metal production and processing chain (production, shaping, maintenance). The identification of different types of metallurgists' tools, some of them specialized, raises questions about the representation of this activity in a wide variety of Early Bronze Age contexts. It also underlines the question of the division of the operating chain in time and space, in particular between the extraction areas, primary metallurgy aimed at metal production and secondary metallurgy dedicated to the shaping or even finishing of the objects. The different occupation contexts from which these tools originate suggest a production of copper alloys, which despite its discretion in the archaeological record, must undoubtedly have been more important than initially envisaged. The presence of such tools in Armorican funerary contexts for the Early Bronze Age echoes these results.

Keywords: metallurgy, copper, lithic tools, early Bronze age, Brittany, use-wear analysis, X-ray fluorescence, portable XRF spectrometry (pXRF), Synchrotron radiation (Sy-XRF).

16-2021, tome 118, 4, p. 671-696 - Y. TCHEREMISSINOFF, R. DONAT, G. GOUDE, M. REMICOURT, H. VERGELY, avec la collaboration de F. CONVERTINI et J.GRIMAUD — Les sépultures et dépôts humains du site néolithique de la Cavalade à Montpellier (Hérault)

Les sépultures et dépôts humains du site néolithique de la Cavalade à Montpellier (Hérault)

Yaramila Tchérémissinoff, Richard Donat, Gwenaëlle Goude, Maxime Remicourt, Hélène Vergély, avec la collaboration de Fabien Convertini et Julie Grimaud

Résumé : Les sépultures et dépôts humains présentés dans cet article ont été découverts sur le site de la Cavalade au sud de Montpellier (Hérault). Il s'agit d'une vaste occupation domestique essentiellement datée du Néolithique final dont seules les structures excavées les plus profondes étaient conservées. Le site, qui a été fouillé par l'Inrap en 2013 sur une surface de presque 3 ha, a livré dix sépultures ou dépôts recelant dix-huit individus, ainsi qu'une grande sépulture collective (Mas Rouge) qui ne sera pas présentée ici. Les dix sépultures, qui se répartissent dans une échelle temporelle comprise entre 3100 et 2650 cal. BC en deux phases principales, sont donc le plus souvent individuelles mais aussi plurielles dans quatre cas. L'une d'entre elle a livré six individus inhumés simultanément et recèle des indices qui plaident pour une procédure dite « d'accompagnement ». Par ailleurs, les résultats de violences ont été mis en évidence sur des ossements pour d'autres individus, ajoutant de nouveaux éléments aux débats sur les modalités de certaines prises en charge sépulcrales au regard des statuts individuels des inhumés. Cette réflexion s'enrichit aussi de données anthropobiologiques et isotopiques très informatives ainsi que de données sur des mobiliers intégrés aux dépôts, outils lithiques et parures au statut particulier.

Mots-clés : Sépultures, dépôts humains, violence, anthropobiologie, isotopes, lithique, parure, Néolithique final, Sud de la France.

Abstract: The burials and human deposits presented in this article were discovered at the Cavalade site near Montpellier (Hérault). This is a large domestic occupation, essentially dating to the Final Neolithic, of which only the deepest features were preserved. The site, excavated by Inrap in 2013 over an area of almost 3 ha, yielded ten burials containing eighteen individuals, as well as a large collective burial (Mas Rouge), which will not be presented here. The ten burials date to 3100-2650 cal. BC corresponding to two main burial phases, they are mainly individual burials with four plural burials, one of which one yielded six simultaneously buried individuals that is evocative of a so-called - peripheral accompaniment- procedure. In addition, bones from other individuals bear traces of interpersonal violence, which renew the debate on the modalities of sepulchral care with regard to the individual status of the buried. This is underlined by precise and informative anthropobiological and isotopic data, as well as results on items integrated into the deposits, lithic tools and ornaments of particular status.

The 18 individuals, adults (men and women), adolescents and children (generally older than 4 years, with 1 exception), are distributed between ten graves. For the phase 2 (3100 - 2900/2880 cal. BC), three individuals were found in 2 pits; for phase 3 (2880 - 2650 cal. BC), fifteen individuals were buried in eight pits. The burials are housed in large pits that were originally small domestic cellars in some cases partially filled in with the bodies being deposited along the walls and under the overhangs. The numerous stones and blocks were used to fill the cavities before burial but also as fill once the burials in place. Most of the burials were protected by perishable casings or stone slabs. These burial modalities reflect the rare examples of ???lesser invested??? burials already known regionally for the period. This new discovery renews the debate on the sociobiological status of the dead concerned. Indeed, some skeletons bear obvious traces of violence, in particular a child between 10 and 14 years who has two depressed skull fractures resulting from blows with a pointed object such as a stone pick or axe heel. Other deceased bear the stigmata of violent blows that they survived and one burial, receiving the simultaneous deposit of six individuals, raises the question of the intentional killing of people to accompany the deceased in the tomb. The deposits, made within a still functional cellar, have a biological symmetry (2 men, 2 women, 2 children of about 6 years old) and show a positional symmetry with the men in the middle, the women near the antechamber and the children placed against the walls. There is no evidence of lethal violence on the skeletons, but two broken flint arrowheads were found, one of which was against the pelvis of one of the men. These observations plead in favour of the deaths being the result of intercommunity and/or interpersonal violence with a probable selection of individuals accompanying the dead. In this regard, isotopic analyses and anthropobiological studies indicate that the men had a different diet to the other individuals of the tomb.

Finally, the collective burial on the same site, belonging to its phase 2, raises questions about the funerary norm, on the one hand, and the possibly diversified kinship and ancestry among the dead, on the other. This is true both over time in terms of the evolution of the local population and within each of the two phases in terms of the diversity of sepulchral settings and funerary practices.

Keywords: Burials, human deposits, violence, anthropobiology, isotopes, lithics, ornament, Final Neolithic, south of France.

15-2021, tome 118, 4, p. 643-670 -L. CHRISTIN, F. DUCREUX, C. FOSSURIER, D. SORDOILLET, avec les participations de F. CATTIN, D. CAMBOU et A. DUFRAISSE — Crémations et monument funéraire campaniformes à Genlis « le Nicolot » (Côte-d’Or, France)

Crémations et monument funéraire campaniformes à Genlis « le Nicolot » (Côte-d'Or, France)

Lucie Christin, Franck Ducreux, Carole Fossurier, Dominique Sordoillet avec les participations de Florence Cattin, David Cambou et Alexa Dufraisse

Résumé : A l'occasion des travaux liés à la réalisation de la ligne à grande vitesse Rhin-Rhône dans les plaines de l'Est dijonnais, deux tombes ont été mises au jour dans le secteur d'une nécropole de l'âge du Fer. Les deux sépultures à crémation découvertes à Genlis « le Nicolot » constituent des témoignages exceptionnels pour cette période encore méconnue en ce qui concerne les pratiques funéraires dans l'Est de la France et en Bourgogne. Jusqu'à présent, ce type de tombe est très peu attesté dans l'Ouest de l'Europe et les sépultures de Genlis témoignent de liens culturels avec l'Europe centrale où les crémations sont mieux documentées.

La première sépulture se caractérise par un monument funéraire remarquable, réalisé sur poteaux de bois et livre deux gobelets à décor à la cordelette et des offrandes animales. Les gobelets décorés à la cordelette sont très rares en Bourgogne et témoigneraient d'une phase précoce du Campaniforme encore difficile à définir sur le plan chrono-culturel mais pour laquelle les influences cordées paraissent plus que probables. La fouille fine complète de cette tombe et les analyses micromorphologiques effectuées sur le remplissage des fossés du monument apportent ici des données encore rares permettant d'envisager des reconstitutions précises de l'architecture et de l'espace funéraire. L'analyse détaillée du mobilier osseux retrouvé en position secondaire, piégé dans le remplissage des trous de poteaux et des fosses de délimitation du monument, montre également la présence de restes animaux non brûlés, parmi lesquels un crâne de bovidé faisant encore référence à des pratiques funéraires attestées du Néolithique final au Bronze ancien en Europe centrale ou dans les régions rhénanes (restes de banquet cérémonial, ornementation de la tombe ou encore dépôt alimentaire pour le défunt ?).

Dans la fosse de la deuxième sépulture ont été déposés les restes d'une crémation, contenus dans une enveloppe péris-sable et accompagnés d'une dotation funéraire, composée d'un vase à décor au peigne de style bourguignon-jurassien, d'un brassard d'archer en schiste, d'un petit poignard en cuivre et d'un outil en silex de type briquet. Le poignard, de type court à languette triangulaire, est sans doute l'objet métallique le plus ancien trouvé en contexte funéraire en Bourgogne.

Ces deux tombes apportent des données considérables sur les pratiques funéraires du Campaniforme et sur le cadre chrono-culturel régional. La place et le rôle de la Bourgogne dans le Campaniforme peuvent ainsi être précisés.

Mots-clés : Bourgogne, Campaniforme, tombe, crémation, poignard en cuivre, gobelets.

Abstract: The building of the high-speed rail track linking the Rhine to the Rhone led to the discovery of two Bell Beaker burials in an Iron Age cemetery located in the plain to the east of Dijon. The Tilles plain is an alluvial environment, shaped by the valleys of the Tille and the Ouche and populated since Late Prehistory, particularly during the Bell Beaker and Early Bronze periods, which have yielded settlements located on the rivers. These burials are the first funerary features discovered in the area.

The two Bell Beaker cremation burials excavated at Genlis "le Nicolot" are remarkable, as still too little is known of the funerary practices of the period in the east of France and in particular in Burgundy. Few Bell Beaker cremation burials are documented in Western Europe, whereas this practice is well known in Central Europe and the Genlis burials underline the strong cultural links with this area. The Genlis cremations are unprecedented in an area where until now only individual inhumations have been found.

One of the burials has a remarkable funerary monument, with a complex layout of corner posts connected by shallow side pits. This architecture delimits a quadrangular space 1.4 m long and 1.2 m wide. The remains of a cremation, certainly originally located in the middle of the monument, were found scattered in the fill of the features that delimit it. The cremation contained two beakers with corded decoration and the remains of an ox skull. The painstaking excavation of this funerary monument and the micro-morphological analyses carried out on the ditch fill provide new data, which has contributed to precise reconstructions of the architecture and the funerary space. The detailed analysis of the bone material in the fill of the post holes and the monument's boundary pits, has also identified unburnt animal offerings, including a bovid skull, which again refers to funerary practices attested from the Final Neolithic and Bell Beaker graves in Central Europe or in the Rhine area as well as in Britain.

This cremation has yielded two beakers with corded motifs and a set of animal bones that may have been offerings. Goblets with corded decor are rare in Burgundy and bear witness to an early Bell Beaker phase that is still difficult to define from a chrono-cultural point of view, but for which corded influences seem more than likely. This early Bell Beaker phase has also been highlighted in the area of Genlis with typical features identified at the sites of Labergement-Foigney, "les Côtes-Robin" and Genlis, "la Moussenière". These features represent the first stages of an occupation that develops during the second half of the Bell Beaker phase and the Early Bronze Age.

The other burial is located in a shallow square pit interpreted as a small wooden chest. The pit housed the cremated remains, which were contained in a perishable envelope and the accompanying grave goods. These are similar to the typical Bell Beaker funerary sets containing a vessel with a Burgundian-Jurassian comb decoration, an archer's cuff made of schist, a small copper dagger and a flint tool, which was probably a lighter. The dagger with its relatively atypical shape is without doubt the oldest metal object found in a funerary context in Burgundy. Unfortunately, the metallographic analyses carried out on this object have not pinpointed the origin of the ore used in its manufacture.

These two burials provide important new information on Bell Beaker funerary practices within a regional chrono-cultural framework, in establishing links between central Eastern France and Central Europe. Funerary monuments, which are delimited by corner posts remain rare in France and show connections with Central Europe where this type of architecture built to house cremation burials, is more frequent.

The cultural links between Central and Eastern France and Central Europe are only part of the story, as there are other probable links with northern Europe, but also the Netherlands and Britain, where funerary practices similar to those at Genlis have also been identified.

These burials have shed new light on the role of Burgundy within the Bell Beaker group. They have also contributed to clarifying the place of Burgundy in the Bell Beaker network, as it transpires that this area played an important role as a buffer zone between the eastern Bell Beaker group influenced by Central and, to a lesser extent, Northern Europe, and the Atlantic Bell Beaker group, for which the cultural links are less obvious. In fact, the so-called Maritime pottery types are not found in the region.

This paper provides detailed analysis of two exceptional and unprecedented Western European Bell Beaker tombs, which also raise the question of the longevity of certain funerary sites used from the beginning of the Bronze Age to the end of the Iron Age, as attested by other local necropolises.

Keywords: Burgundy, Bell Beakers, graves, cremation, copper dagger, beakers.

14-2021, tome 118, 4, p. 619-642 - E. VAISSIE, M. MASSOULIE, J. COMBIER †, S. SORIANO — Nouveau regard sur le Moustérien

de Bourgogne : première relecture des industries lithiques de la grotte de Vergisson IV (Saône-et-Loire)

Nouveau regard sur le Moustérien de Bourgogne : première relecture des industries lithiques de la grotte de Vergisson IV (Saône-et-Loire)

Erwan Vaissié, Marine Massoulié, Jean Combier, Sylvain Soriano

Résumé : Le Paléolithique moyen de Bourgogne présente encore aujourd'hui une image hétérogène, à la jonction entre différents ensembles techno-culturels dont les influences semblent se traduire dans la diversité des industries connues. Les nombreuses redéfinitions des faciès moustériens selon une approche technologique entreprises ces dernières années mènent aujourd'hui à une meilleure compréhension de la variabilité des techno-complexes du Paléolithique moyen, en même temps que des études récentes tendent à mettre en évidence des spécificités culturelles régionales pour la Bourgogne. Le site de Vergisson IV (Saône-et-Loire) est l'un des rares sites stratifiés en milieu karstique de la région et son étude s'inscrit dans cette entreprise de révision et dans le débat sur la variabilité des industries du Paléolithique moyen. Nous présentons ici les premières données issues de la révision pétro-techno-économique des industries du gisement, initialement attribuées à un Moustérien Quina.

La relecture des données de la fouille de J. Combier a conduit à individualiser deux ensembles archéo-stratigraphiques. Ils se distinguent par leur composante techno-typologique et leurs comportements techniques et d'approvisionnement, mais sont semblables dans le statut économique de l'occupation. Les deux unités témoignent ainsi de l'introduction sur le site de matériaux locaux sous forme de matrices ou de supports déjà en grande partie élaborés ou consommés, et les indices d'activité sur le site semblent principalement liés à la phase de transformation et d'entretien de l'équipement lithique au détriment de la production. L'outillage retouché, largement dominé par les racloirs, est très nombreux (> 35%) et concerne une large variété de supports. L'ensemble supérieur illustre des séquences opératoires courtes (principalement unipolaires), sans grande prédétermination ou configuration/gestion des volumes, et une retouche abrupte de supports épais caractérisant un cycle de gestion long de l'outillage. Les comportements de collecte des matériaux siliceux sont généralistes. Malgré une apparente proximité typologique entre cette unité et l'entité du Quina rhodanien, la faible représentation de certaines pièces caractéristiques (outils à amincissement ou à caractère bifacial plano-convexe) et des divergences dans les modalités de débitage (unipolaire vs centripète) incite à la prudence. L'unité inférieure repose quant à elle sur un système de production Levallois, avec une sélection particulière des matériaux de bonne qualité, et montre dans son spectre typologique des outils bifaciaux et pointes foliacées plano-convexes. Elle trouve un écho avec certains sites du Paléolithique moyen récent du Chalonnais, suffisamment pour soulever la question de l'existence d'une entité techno-culturelle propre à cette région. Pour les deux unités, quelques objets importés sous la forme de produits isolés (retouchés ou non) illustrent des circulations plus importantes axées vers le nord (unité inférieure et supérieure) et l'ouest du gisement (unité inférieure), entre les vallées de la Saône et de la Loire.

Les caractéristiques pétro-techno-économiques des deux unités les démarquent des composantes Quina du Sud-Est de la France, et semblent davantage être la conséquence des stratégies de gestion de l'outillage et de la position du site au sein du cycle techno-économique des groupes et de leur territoire. Malgré l'absence de données chronologiques et archéoozologiques, les caractéristiques des assemblages lithiques semblent s'accorder avec des occupations courtes, répétées et anticipées (halte temporaire), probablement intégrées dans un circuit de mobilité saisonnière plus vaste et/ou un schéma régional plus complexe de stratégie logistique. Le site de Vergisson IV illustre également un exemple intéressant de persistance du statut économique d'un site en dépit d'apparentes variations techno-culturelles des groupes humains le fréquentant.

Mots-clés : Paléolithique moyen, Bourgogne, techno-économie, matières premières lithiques, territoires, mobilité.

Abstract: The Middle Palaeolithic of Burgundy still presents a heterogeneous image, at the junction between different techno-cultural complexes whose influences seem to be reflected in the diversity of known industries. The numerous redefinitions of Mousterian facies according to a technological approach undertaken in recent years are now leading to a better understanding of the variability of Middle Palaeolithic techno-complexes, while recent studies tend to highlight regional cultural specificities for Burgundy. The Vergisson IV site (Saône-et-Loire) is one of the rare stratified sites in a karstic environment in the region and its revision is part of this revision process and of the debate on the variability of Middle Palaeolithic industries. We present here the first data from the petro-technical-economic revision of the industries of the deposit, initially attributed to a Quina Mousterian.

Despite the low density of remains, this study shows the individualisation of two archaeological-stratigraphic units (lower and upper unit). They differ in their techno-typological component and their technical and supply behaviour, but are similar in the economic status of the occupation. The two units bear witness to the massive use of the secondary flint formations near the site (Cretaceous resources of the Mâconnais flint clays and Jurassic flints accessible in the colluvium of the Mâconnais flint formations) via the introduction onto the site of raw materials in the form of matrices or blanks that had already been largely elaborated or consumed. The indications of knapping activities on the site seem to be mainly linked to the phase of transformation and maintenance of the lithic equipment to the detriment of the production represented by a relatively expedient debitage (provisioning of place). A few objects made of more distant raw materials illustrate the introduction, in the form of ???personal gear???, of pre-determined raw or retouched products or with evidence of refaction of the cutting edges alone on site (provisioning of individuals; Kuhn, 1995). They testify to more important circulations oriented towards the north in the Chalonnais/Dijonnais (lower and upper unit), but also towards the west of the deposit (lower unit), between the Saône and Loire valleys. The retouched tools, largely dominated by scrapers, are very numerous (> 35%) and concern a wide variety of blanks.

The upper set illustrates short operating sequences (mainly unipolar), without much pre-determination or configuration/management of volumes, and abrupt retouching (frequently semi-Quina) of thick supports characterising a long tooling management cycle. The collection behaviours of siliceous raw materials reflect a generalist strategy and should probably be linked to the low level of requirement of the groups related with their technical production systems. Despite an apparent typological proximity between this unit and the Rhodanian Quina entity, the poor representation of certain characteristic pieces (thinning tools or plano-convex bifacial tools) and the divergence in the debitage methods (unipolar vs. centripetal) encourage caution. The lower unit is based on a Levallois production system, mainly unipolar, with a particular selection of good quality materials. The blanks produced are more slender, the retouching is mostly grazing and there are characteristic pieces in its typological spectrum, notably bifacial supports with a plano-convex section of fine workmanship, or scrapers reminiscent of bogenspitzen. It echoes certain sites of the late Middle Palaeolithic of the Chalonnais (Grottes de la Verpillière I and II, La Roche, La Clôsure) and could contribute to the recognition of a probable techno-cultural entity specific to this region.

The petro-techno-economic characteristics of the two units distinguish them from the Quina components of south-eastern France, and seem to be more the consequence of the management strategies of the tools and the position of the site within the territory and techno-economic cycle of the groups. Despite the lack of chronological and archaeozoological data, the characteristics of the lithic assemblages seem to be consistent with short, repeated and anticipated occupations (temporary halt), probably integrated into a wider seasonal mobility circuit and/or a more complex regional logistic strategy. The Vergisson IV site also illustrates an interesting example of the persistence of the economic status of a site despite the apparent techno-cultural variations of the human groups frequenting it.

Keywords: Middle Palaeolithic, Burgundy, techno-economy, lithic raw material, territories, mobility.

13-2021, tome 118, 3, p. 519-568 - F. Couderc, F. Bordas, J.Gomez de Soto, C. Le Carlier de Veslud, P.-Y. Milcent, S. Révillon — À la charnière des espaces médio- et ibéro-atlantiques et continentaux : l’ensemble métallique du Bronze final atlantique 3 an

A la charnière des espaces médio- et ibéro-atlantiques et continentaux : l'ensemble métallique du Bronze final atlantique 3 ancien d'Hourtin (Gironde, France)

Florian Couderc, Francis Bordas, José Gomez de Soto, Cécile Le Carlier de Veslud, Pierre-Yves Milcent, Sidonie Révillon

Résumé :

L'érosion du littoral aquitain depuis plusieurs décennies révèle régulièrement des vestiges archéologiques enfouis sous les dunes côtières. En 1993, 132 objets en alliage cuivreux, pour une masse de 4,628 kg, ont été découverts sur la plage au nord d'Hourtin (Gironde). Ces objets sont aujourd'hui conservés au Musée d'Aquitaine de Bordeaux. Même s'il est impossible de l'affirmer avec certitude, l'homogénéité typologique des objets et leur concentration sur une petite surface sur la plage laissent suggérer qu'il s'agissait bien à l'origine d'un seul et même dépôt du Bronze final disloqué par l'océan.

Cet ensemble est remarquable par plusieurs aspects. Il s'agit d'un des rares connus du Bronze final atlantique 3 ancien (seconde moitié ou courant du Xe s. av. J.-C.) sur la façade atlantique française. Il concentre des objets aux affinités culturelles très variées : armements de type médio-atlantique, parures et pommeau à volutes de type continental, ainsi qu'une hache et possiblement des épées et des parures de type ibéro-atlantique. Cette diversité typologique, la faible fragmentation des parures, ainsi que sa localisation géographique, font du dépôt d'Hourtin un unicum pour le Sud-Ouest de la France. Les analyses chimiques élémentaires et isotopiques, ainsi que l'étude typologique des objets, permettent d'illustrer cette importance des échanges culturels et économiques durant le Xe s. avant J.-C., période encore méconnue en comparaison de celle du Bronze final atlantique 3 récent (IXe s. av. J.-C.), largement mieux documentée dans le nord-ouest de la France.

Mots-clés : Aquitaine, Gironde, dépôt métallique, Bronze final atlantique 3 ancien, paysage, culture matérielle

Abstract:

The Médoc region is located in the south-west of France on the Atlantic coast. Many archaeological remains have been discovered under the sand dunes over the course of the last few decades due to the erosion of the Aquitaine shoreline. These include hoards, isolated metal objects, pottery, preserved wooden posts and flints. In 1993, a detectorist discovered 154 copper alloy objects on the beach north of the town of Hourtin. The objects were given to the Aquitaine Museum of Bordeaux, where they are still preserved today. The artefacts were scattered over a perimeter of approximately 70 meters and some were found to be clearly earlier or more recent than the Bronze Age. However, 132 objects (weighing 4,628 kilograms) do date from the end of the Bronze Age and more specifically from the Early Atlantic Late Bronze Age 3 (first half of the 10th century BC). We cannot guarantee that this discovery is a hoard, but the homogeneity and the composition of the set testify that these objects were probably deposited in the same place. Initially, the hoard was deposited inland, and not on the coast which was further out to sea at the time of the Bronze age as indicated by the clay banks that lie beneath the dune. The landscape of the Médoc has evolved a lot since Late Bronze Age, as during this period, the coastal area was wetter, overtaken by marshes with streams connecting to the ocean or the Gironde estuary.

More than fifty hoards dating to Middle Bronze Age have been found in the Médoc mainly during the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries. They contain mainly flanged axes and palstaves. The Hourtin discovery is the first located on the coast where metal hoarding does not seem to have been common practice during the Late Bronze Age where hoards and single finds are very uncommon. Late Bronze Age 2 and Late Bronze Age 3 (1150 ??? 800 BC) hoards in Gironde have been discovered, along the Garonne and Dordogne rivers on the other side of the Gironde estuary, but not on the coast. Furthermore, the composition of the Hourtin hoard is original with Ibero-Atlantic objects such as axes and swords, which are often fragmented. The fragmentation is typical of the medio-Atlantic area at this time. Most of the bracelets are however complete in the Hourtin hoard, which is not always common in the medio-Atlantic area. The hoard contains objects from continental productions, such as Corent type bracelets and a Klentnice type sword pommel, uncommon in France, which has two volutes inserted in a wooden handle. Only one confirmed and three possible Klentnice pommels have been found in France, notably in Brasles (Picardy). They are also rare in the rest of Europe and are generally found in Denmark and Eastern Europe. According to H. Müller Karpe, this type of sword dates from Hallstatt B2.

The presence of these objects indicates dynamic long-distance trade during the Late Bronze Age. The Médoc is located between two Ibero- and medio Atlantic cultural networks and the Hourtin discovery highlights cultural interaction around the Gironde estuary. The Pyrenees and the Atlantic coast are not obstacles for cultural contacts and trade between the north and the south of the Atlantic area and the circulation of metallic objects was important between these two entities.

The elemental composition analyses of the metal objects are very insightful. When making the objects the artisan choses the main elements of alloy, which are copper, tin and lead . The lead content of Late Bronze Age copper alloy makes interpretation of the analyses complex as it is not possible to determine if the lead was naturally present in the copper ore or if it was specifically added. Trace elements such as zinc, bismuth, antimony and arsenic can discriminate Continental, Atlantic and Iberic-Atlantic productions, however the objects of Hourtin hoard show varying results and it has not been possible to determine the origin of the metals used. The analyses do underline the important trade in metal resources during Late Bronze Age all over Europe. We cannot clearly understand the role of the south-west of France in the trade dynamics of the south of the Atlantic area no other metal hoards have been found in this area. We hope that new discoveries will give us a better understanding of the trade role of the Médoc and of the south-west of France between the various Late Bronze Age cultural and economic networks.

12-2021, tome 118, 3, p. 475-518 - Ch.-C. Besnard-Vauterin, G. Auxiette, M. Le Puil-Texier, C. Marcigny — Une enceinte de type ring fort du Bronze final et un enclos d’habitat du premier âge du Fer à Mondeville (Calvados

Une enceinte de type ring fort du Bronze final et un enclos d'habitat du premier âge du Fer à Mondeville (Calvados)

Chris-Cécile Besnard-Vauterin, Ginette Auxiette, Myriam Le Puil-Texier, Cyril Marcigny

Résumé :

La fouille préventive réalisée à Mondeville « 31 rue Nicéphore Niepce » a permis d'identifier deux phases d'occupation, l'une datée du Bronze final et l'autre du premier âge du Fer. La première est matérialisée par un double dispositif fossoyé de plan circulaire, partiellement connue dans l'emprise. Les fossés ont livré des rejets de faune et un important dépôt, mettant en évidence un spectre faunique dominé par le boeuf et offrant des observations intéressantes sur des pratiques de consommation « extraordinaires ». Une autre particularité concerne la présence d'ossements humains isolés au sein des fossés et l'alignement de restes de corps humains, ayant fait l'objet de manipulations post-sépulcrales. Cette enceinte, datée entre 1220 et 907 avant notre ère sur la base de cinq analyses 14C, est à rapprocher avec les enceintes circulaires monumentales ou ring forts, connus en Grande-Bretagne pour le Bronze final et identifiés en Normandie à Cagny et Malleville-sur-le-Bec. Le statut de ce site demeure à ce jour énigmatique, tout comme son rôle dans le panel des formes d'habitats pour les phases finales de l'âge du Bronze.

L'enclos du premier âge du Fer est formé par deux fossés rectilignes, composant un plan probablement quadrilatéral mais incomplet. Parmi les vestiges internes, une structure de captage d'eau et des fosses à vocation de stockage ou d'extraction témoignent du caractère domestique et agro-pastoral du site. La céramique permet d'avancer une datation du Hallstatt moyen pour la fondation de cet enclos, avec une perduration au Hallstatt final. Sa configuration s'intègre parfaitement dans la vague d'apparition des premières formes d'habitat encloses au cours du Hallstatt moyen/final, telle que reconnue à ce jour dans la plaine de Caen.

Mots-clés : double enceinte circulaire, ring fort, Bronze final, habitat enclos, Hallstatt, fossés, céramique, faune, sépultures.

Abstract:

The excavation at Mondeville « Rue Nicéphore Nièpce » located in the Caen plain has led to the unexpected discovery of a Protohistoric site with two chronological phases. A double circular enclosure, dating to the end of the Bronze Age is of major interest for landscape studies and ongoing research on settlements for this period. A second settlement enclosure dating to Early Iron Age sheds new light on this densely populated area during Late Prehistory. The Late Bronze Age enclosure comprises two incomplete curved parallel ditches made up of oval shaped segments of varying length. Two breaks in the ditches provide an entrance to the south-west and the south-east. The excavation covered a 2750 m² area of a site estimated at almost 6 000 m². The outer diameter of the enclosure is 90 m. As the site has two phases, it has not been possible to attribute features to this first phase due to the lack of datable artefacts.

The fill of the two ditches, specifically the lower and intermediary levels, are very similar but fail to give any indication as to the location of a bank. The upper fill of the inner ditch is an anthropogenic layer containing artefacts dating to Hallstatt D that indicate that the ditch was levelled off during the site's later phase. The large deposits of mainly cattle bones in the ditches has shed light on meat consumption on the site, with the slaughter of significant numbers of young animals. The high proportion of skulls some of which were exposed and the high mni indicate 'extraordinary' 'consumption' during specific manifestations. Another interesting aspect is the presence of some human bone in the fill with the alinement of the bones of five incomplete skeletons that showed marks of post-mortem manipulation.

The radiocarbon dates of three samples of animal bone from the lower fill and human bone indicate 1220 to 907 BC. The pottery is similar to the Plain Ware and Decorated Ware phases from Manche-Mer-du-Nord sites dating to the middle and late phases of the Late Bronze Age.

The Mondeville site plan is similar to the Late Bronze Age monumental circular enclosures or ring forts of Great Britain. The Normandy ring forts of Cagny (Calvados), Malleville-sur-le-Bec (Eure) and Lamballe « La Tourelle » (Côtes-d'Armor) in Brittany are the only French examples. The radiocarbon dates of these sites and their British counterparts (Mucking « North Ring », Springfield Lyons, Thwing, Grimthorpe and Tintore) indicate that these enclosures were in use from the 13th to the 9th century BC.

After several centuries, the Late Bronze Age ditches were two thirds filled in leaving a slight depression in the landscape obviously still visible during the Iron Age. The Hallstattian enclosure partially follows its Late Bronze age counterpart with a similar orientation of its entrance. The ditch is finally filled in by domestic and combustion waste from the Iron Age site.

The Hallstatt D enclosure comprises two perpendicular ditches forming two sides of a rectangle. The enclosed area with its western entrance has an estimated surface area of 5700 m² accessible. The pottery dates a number of features to the Hallstatt D, which include a feature to collect water, storage pits or extraction pits. These features have provided diverse artefacts characterising the domestic and agro-pastoral activities of the site. The zooarchaeological study reveals that meat and by products were mainly obtained from cattle rearing. The pottery finds date the enclosure dates to the Hallstatt D1/D2 phase and indicate that it remained in use until the Hallstatt D3. A Couville type amorican socketed axe, which constitutes a particularly important find in a domestic context, was retrieved from the enclosure ditch. The site also includes five graves, three date to the Hallstatt period and two to the Middle La Tène phase. The two La Tène graves are located in the ditch fill and show that the site was still in use during this later period when a new enclosure was built to the south of the original site.

The enclosure's layout is typical of enclosed settlements built during the Hallstatt D as has been observed in the Caen plain. The site encloses more than a hectare, which is significantly larger than contemporary sites. It is therefore tempting to see a link between the enclosure's size and the high status of the earlier Bronze Age enclosure. Another important fact about the site is that it is located in an area densely occupied at the end of the Early Iron Age.

Keywords: double circular enclosure, ring fort, Late Bronze Age, enclosed settlement, Early Iron Age, ditches, pottery, animal bone remains, burials.

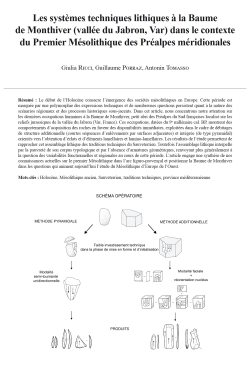

10-2021, tome 118, 3, p. 427-451 - G. Ricci, G. Porraz, A. Tomasso — Les systèmes techniques lithiques à la Baume de Monthiver (vallée du Jabron, Var) dans le contexte du Premier Mésolithique des Préalpes méridionales

Les systèmes techniques lithiques à la Baume de Monthiver (vallée du Jabron, Var) dans le contexte du Premier Mésolithique des Préalpes méridionales

Giulia Ricci, Guillaume Porraz, Antonin Tomasso

Résumé :

Le début de l'Holocène consacre l'émergence des sociétés mésolithiques en Europe. Cette période est marquée par une polymorphie des expressions techniques et de nombreuses questions persistent quant à la nature des scénarios régionaux et des processus historiques sous-jacents. Dans cet article, nous concentrons notre attention sur les dernières occupations humaines à la Baume de Monthiver, petit abri des Préalpes du Sud françaises localisé sur les reliefs jurassiques de la vallée du Jabron (Var, France). Ces occupations, datées du 9e millénaire cal. BP, montrent des comportements d'acquisition des roches en faveur des disponibilités immédiates, exploitées dans le cadre de débitages de structure additionnelle (courtes séquences d'enlèvements par surfaces adjacentes) et intégrée (de type pyramidal) orientés vers l'obtention d'éclats et d'éléments lamellaires et lamino-lamellaires. Les résultats de l'étude permettent de rapprocher cet assemblage lithique des traditions techniques du Sauveterrien. Toutefois l'assemblage lithique interpelle par la pauvreté de son corpus typologique et par l'absence d'armatures géométriques, renvoyant plus généralement à la question des variabilités fonctionnelles et régionales au cours de cette période. L'article engage une synthèse de nos connaissances actuelles sur le premier Mésolithique dans l'arc liguro-provençal et positionne la Baume de Monthiver dans les questions qui animent aujourd'hui l'étude du Mésolithique d'Europe de l'Ouest.

Mots-clés : Holocène, Mésolithique ancien, Sauveterrien, traditions techniques, province méditerranéenne.

Abstract:

Mesolithic heralds a period characterised by miniaturized technologies, but the nature and significance of this chronocultural phase still requires clarification. Research questions arise in particular with regard to the underlying ecological and historical driving forces at the transition from the Pleistocene to the Holocene. In this paper, we focus on the Mesolithic occupations of La Baume de Monthiver.

La Baume de Monthiver is a small rock shelter located in the middle Jabron valley in the Southern French Pre-Alps (Var, France ??? fig. 1). The site opens to the east along the Jurassic cliff of Monthiver at an altitude of about 900 m asl., a few hundred metres above the Palaeolithic site of Les Prés de Laure.

A first excavation was carried out at La Baume de Monthiver in 2017 with the aim of assessing the archaeological potential of the deposits (Porraz et al., 2018). The excavation strategy took into account the existence of a clandestine trench. Two excavation areas were opened: the first area consisted of a vertical exploration of the deposits on 1 m² until bedrock (test-pit 12), the second area (sector G-F) comprised of a horizontal exploration of the uppermost deposits on a surface of ca. 2.5 m² (fig. 2).

A stratigraphic sequence of about 90 cm was exposed, subdivided into 23 stratigraphic units (SUs) and grouped into seven sedimentary phases. Two main archaeological phases separated by a sterile horizon have been recognized. The lower phase documents ephemeral occupations from the Upper Palaeolithic, with radiocarbon dating to the 14th millennium cal. BP. The upper phase is much richer in terms of the archaeological record and documents technological traditions that refer to the Mesolithic. Here, we focus on the upper phase M-B' (fig. 2).

For the phase M-B', four radiocarbon dates are available, positioning the SU M-B???3 within the 9th millennium cal. BP (fig. 3; tab. 1). At a regional scale, namely within the liguro-provencal arc, the first Mesolithic is represented by the Sauveterrian, a technological tradition that finds its earliest expressions during the 12th millennium cal. BP at the site of Romagnano Loc III in Italy (Fontana et al., 2016) and lasts until the 8th millennium cal. BP at the site of La Grande Rivoire in the Northern French Pre-Alps (Angelin et al., 2016). The Sauveterrian features a lithic technology based on the selection of local raw materials, the production of small blanks with various morphologies, the manufacture of backed points and of geometric microliths.

Within the phase M-B??? of La Baume de Monthiver, more than 4 000 lithic elements have been recorded (tab. 2). All of them are made on flint. The blanks show a high degree of alteration (white patina, burning, etc.), which constrained the petrographic study. However, all pieces allowing an assignment to a geological formation (ca. 45% of the sample) demonstrate a strictly local procurement. Most of the raw materials, from Tertiary and Turonian formations, were collected in the Jabron alluvial deposits, while Valanginian flints were available in the neighbouring primary formations (tab. 3).

Local rocks were exploited following two chaînes opératoires (fig. 9). One concerned a unidirectional exploitation of a pyramidal shaped core (type E2; see Boëda, 2013). The other consisted of a series of unidirectional removals alternating from orthogonal surfaces of exploitation (type D2; ibidem). Both chaînes opératoires were oriented towards the production of small blanks, including blades, bladelets and elongated flakes. The various stigmata suggest the application of free hand knapping with a hammerstone alternating from an internal to a more marginal percussion.

The formal tools are not numerous and were only manufactured on bladelets. This corpus is only composed of microlithic backed tools (fig. 4, nos 27-33) with a single or double back (tab. 5); all of them are broken.

The results of the study conform to what is known as being characteristic of the Sauveterrian techno-complex. The lithic assemblage of the phase M-B??? of La Baume de Monthiver documents technical behaviours that adapted to local raw material availabilities. The reduction strategies demonstrate a low investment in terms of preparation and management of the convexities. The knappers intended to produce a set of small blades, bladelets and flakes with various morphologies, within a dimensional threshold that never exceeded 60 mm (fig. 5).

While the lithic assemblage of La Baume de Monthiver shows many similarities with the Sauveterrian, it differs with regard to its typological corpus. The sample of La Baume de Monthiver is characterised by a low number of formal tools, a low typological diversity and the absence of geometrics. A literature review highlights indeed quite an important typological variability at that time, which raises questions about the functional and/or regional variability that occurred during the first phase of the Mesolithic in Western Europe.

As documented at other Sauveterrian sites, the lithic assemblage of La Baume de Monthiver illustrates a procurement strategy based on immediate availabilities, suggesting a mobility system based on frequent displacements. Other proxies found at La Baume de Monthiver, such as Mediterranean seashells (Columbella rustica) used as ornaments, indicate a much wider socio-economic network. Based on the present set of data, we are prone to interpret the lithic assemblage of La Baume de Monthiver as a techno-economic expression of small groups who favoured short-term occupations within the framework of exploration and exploitation of the resources from the Southern Pre-Alps. Further examination of the lower Mesolithic occupations of La Baume de Monthiver as well as of the sedimentary archives of the Jabron valley will contribute to a new narrative of the cultural and paleo-environmental transformations that hunter-gatherers groups experienced at the onset of the Holocene in the South-East of France.

Keywords: Holocene, Early Mesolithic, Sauveterrian, technological traditions, Mediterranean province.

09-2021, tome 118, 2, p. 363-388- A. Schmitt, S. Van Willigen, A. Vignaud - Les inhumations du Néolithique et de l'âge du Bronze du Rouergas (Saint-Gély-du-Fesc) et leur contexte régional

Les inhumations du Néolithique et de l'âge du Bronze du Rouergas (Saint-Gély-du-Fesc) et leur contexte régional

Aurore Schmitt, Samuel Van Willigen, Alain Vignaud

Résumé :

Le site du Rouergas, fouillé en 1996, a livré, dans sa partie nord, des vestiges du Néolithique moyen. Dans la partie sud, ont été découvertes deux cabanes fontbuxiennes écroulées et des structures en creux. Le site a connu trois épisodes mortuaires. La fosse 123 contenait un dépôt primaire d'enfant, déposé sur le côté droit, tête au nord-ouest, ainsi qu'un bloc parallélépipédique de grandes dimensions qui servait sans doute de signalisation. La datation sur os indique qu'il s'agit d'une inhumation du début du Néolithique moyen. Les fosses 109, 120 et 122, situées à proximité les unes des autres, témoignent d'un deuxième épisode mortuaire du site. Creusées dans le substrat, elles ont chacune livré les restes d'un défunt (un individu de taille adulte et deux enfants de moins de 5 ans). Les datations radiocarbones sur chacun des individus les situent à la fin du Néolithique moyen alors que les quelques éléments de mobilier issus des mêmes creusements sont attribuables à des périodes plus récentes (Néolithique final et Antiquité). Il est donc permis de supposer que, dans ces cas, le creusement de ces fosses a perturbé des inhumations antérieures. Les vestiges humains qui ont séjourné aux abords ont été réensevelis lors du comblement des fosses. Le dernier épisode mortuaire, daté de l'âge du Bronze moyen, est une inhumation d'enfant, déposé sur le dos, les jambes hyperfléchies sous les cuisses, dans les ruines d'une des cabanes fontbuxiennes. Cette configuration ne permet pas d'affirmer qu'il s'agit d'une sépulture.L'inhumation de la fosse 123 est bien conservée et date de la première moitié du Ve millénaire avant notre ère, une période charnière pour la région. Depuis quelques années, les découvertes qui correspondent à cet horizon chrono-logique se multiplient et permettent de poser quelques jalons sur le dossier des pratiques mortuaires du Midi de la France durant cette période. Nous en proposons un panorama fondé sur 14 sites de comparaison. Certains éléments apparaissent dès le Néolithique ancien (lieu de dépôt, position sur le côté gauche dominante, présence de parure, traite-ment non funéraire, absence de regroupement des morts), alors que d'autres, notamment les dépôts en fosse circulaire, semblent faire leur apparition à ce moment.

Mots-clés : Néolithique moyen, âge du Bronze, inhumation, Midi de la France, pratiques mortuaires, sépultures.

Abstract: The site of Rouergas excavated in 1996 yielded, in its northern part, remains dating to the Middle Neolithic as well as four features containing human remains dated to the "Chasséen". Two collapsed fontbuxian huts, pits and a burial in the ruins of one of the huts were discovered in the southern part of the site. This paper proposes to present the features that yielded human remains that were subsequently radiocarbon dated and to place them in their regional context. The site has three mortuary phases. The features 109, 120 and 122 were disturbed, whereas the pit 123, located nearby, was found to be intact. It contained the primary deposit of a child (2-4 years old), deposited at the bottom of the pit, with the head to the northwest. The upper part of the body was slightly turned on the right side, the arms were placed away from the body in a symmetrical position and the forearms flexed. The lower limbs were folded on the right side. Most of the movement of the bones during decay occurred within the initial volume of the corpse. A large parallelepiped shaped block was located in the middle of the pit and perpendicular to the body, separated by a layer of sediment. The block probably served as a tomb marker and its presence may explain the preservation of the burial, which was not the case for the re-used pits 109 and 122. The radiocarbon dating of a bone sample indicates the early Middle Neolithic. Pits 109 and 122 contained archaeological material dating to the Middle and Late Neolithic, which include human remains. The study of the pottery from the fill, in correlation with the stratigraphy, suggest that the human remains come from earlier deposits that were disturbed when the pits were dug. The skeletal remains are incomplete, but do indicate an individual of adult size and a child under the age of 5 years. It has not been possible to render the mode of the deposit (primary, secondary), nor the mode of decay. Pit 120 is slightly different as it contains artefacts from the Middle Neolithic and the bones were radiocarbon dated to the end of this period. However, it is likely that the events leading to their deposition follow the same scenario as for pits 109 and 122. It is however possible that the human remains, an individual younger than five years, are in their original deposit. Radiocarbon dating places these 3 deposits at the end of the Middle Neolithic. These human deposits, the second funerary phase of the site, were probably grouped in an area of the site. Their present condition provides little information other than the intention to group the all the burials (adults and children) together near to a settlement. The last funerary phase (SU 810) dates to the Middle Bronze Age. It involves the discovery of the skeleton of a child aged between 6 and 10 years, covered by debris from the collapse of the roof and walls of one of the fontbuxian huts. The context and the position of the body, on its back, with its lower legs hyperflexed under the thighs, are unusual for this period in the area and it seems unlikely that these remains were laid to rest in a grave. The use of a Fontbuxian settlement as a funerary site in the Bronze Age is documented on at least one other site in the area, but in this case, the funerary context of the burial is clear. The recent discoveries from 14 sites dating to 5000-4400 BC have underlined trends in mortuary practices in the South of France. Primary individual deposits are most frequent The position of the deceased is mostly on the left side but three individuals were deposited on their right side. A child was buried in a sitting position and another deposit involved an adult corpse that has been thrown into a storage pit from above and not properly deposited. Other treatments of the body are also documented. Evidence of decarnisation was found on two sites. We suspect that cannibalism occurred on the site "La Baume de Fontbregoua" but this settlement deserves further investigation to determine whether it was endo-cannibalism (a funerary practice) or exo-cannibalism involving an enemy.. Most of the burials have no grave goods, except for three with ornaments. We have documented both male and female burials but children are underrep-resented except in the collective grave at "Les Bréguières". The burials are generally housed in pits, either dug for the purpose of burial or re-used, or in natural cavities or in open settlements. Some practices that date back to the Early Neolithic persist well into the first half of the Vth millennium: burials in caves or in especially designated open areas, the positioning of the body on its left side, the use of grave markers and the presence of ornaments. Pottery and lithic tools remain rare and many deceased have no grave goods whatsoever. There are no large funerary groups in dedicated "cemeteries", but collective tombs are documented even if the ideology behind this practice is unlikely similar to the ideology that developed during the Late Neolithic. In the Vth millennium, the main innovation is the re-use of large circular domestic pits for burials. This new custom is seen as specific to the Middle Neolithic but does in fact appear earlier. As with the Early Neolithic, the funerary nature of these human depos-its is not necessarily systematic.

Keywords: Middle Neolithic, Bronze age, burial, South of France, mortuary practice, tomb

08-2021, tome 118, 2, p. 323-362 - F. Lorenzi, A. Colonna, M. Dubar, C. Nicollet, B. Zamagni, J. Conforti

Économies des populations néolithiques de Corse : apport de l'étude typo-technologique du matériel en pierre polie et du macro-outillage du site de A Guaita (Morsiglia, Haute-Corse)

Françoise Lorenzi, Antonia Colonna, Michel Dubar, Christian Nicollet, Barbara Zamagni, Jacopo Conforti

Résumé : Au Mésolithique, très peu de traces d'occupation humaine sont attestées dans le Cap Corse, comme dans l???ensemble de l'île. Ce n'est qu'avec les vagues successives de néolithisation, et surtout dans le courant du VIe millé-naire avant notre ère, que des petits groupes humains s'installent majoritairement le long des côtes dans des abris. Ils pratiquent une économie de subsistance axée sur une agriculture sommaire et un élevage adapté au relief (ovicaprinés et suinés) tout en pratiquant cueillette, chasse et pêche. Situé sur une petite colline littorale au nord-ouest du Cap Corse, le gisement de A Guaita a livré, sur une terrasse sommitale, deux occupations successives du Néolithique ancien et moyen (fin du VIe millénaire-fin du IVe millénaire BCE), dont une grande structure d'habitat attribuable au Néolithique moyen. De nombreux vestiges céramiques et lithiques propres à chacune des occupations ont été recueillis, dont plus d'une soixantaine d'outils en pierre non taillée (macro-outillage) et en pierre polie, rarement publiés, sinon étudiés en Corse. En effet, les meules, molettes, lissoirs, percuteurs et lames polies sont souvent analysés, mais d'autres outils (enclumes, aiguisoirs, pièces intermédiaires ou outils multifonctionnels) sont très rarement évoqués. Sans doute n'apparaissent-ils pas en aussi grand nombre sur de nombreux sites insulaires. Depuis quelques années, plusieurs publications nationales ont abordé une étude systématique de ces pièces. Nous avons donc réalisé une description et une analyse par catégorie de notre corpus, et chacun de ces groupes est présenté et illustré. La localisation spatiale des pièces indique les aires probables d'activité des groupes. En plus d'un examen macroscopique systématique, plusieurs éléments ont fait l'objet d'analyses pétrographiques qui ont mis en évidence leur origine locale : en effet, la quasi-totalité de ces outils sont issus de galets, ou façonnés à partir de blocs qui proviennent de l'environnement immédiat du site (approvisionnement local) ou du Cap Corse (microrégional). L'ensemble de ces données (éléments de meunerie, outils en pierre polie, mais aussi macro-outils servant au façonnage, au débitage, ou à la production d'industries en pierre taillée) laisse supposer des activités de production nécessaires à la vie des occupants du site. Enfin, des rapprochements culturels sont envisagés avec des sites corses et d'Italie centrale, ainsi que les circuits et échanges que ces artefacts semblent suggérer dans l'aire tyrrhénienne.

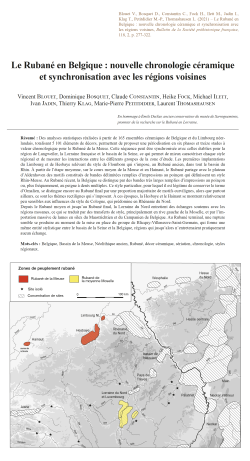

Mots-clés : Néolithique ancien, Néolithique moyen, outillage en pierre polie, macro-outillage, étude et analyse pétro-graphique, échanges en contexte tyrrhénien.