Prix : 15,00 €TTC

06-2024, tome 121, 2, p.211-241 - Brunet V., Millet-Richard L.-A., Durand J., Gosselin R., Blaser R. (2024) – Des croissants au pays des « livres de beurre » à la fin du Néolithique

Des croissants au pays des « livres de beurre » à la fin du Néolithique

Véronique Brunet, Laure-Anne Millet-Richard, Juliette Durand, Renaud Gosselin, Romana Blaser, avec la collaboration d'Ève Boitard-Bidaut

Résumé : La découverte récente en contexte préventif de croissants en silex en Île-de-France, en dehors de la Touraine où ils ont été identifiés la première fois, est l'occasion de s'interroger sur cet outil si particulier et rare. L'objectif de notre recherche était de recenser cet objet dans la bibliographie à l'échelle nationale et hors des frontières de l'Hexagone, d'en déterminer le nombre, les contextes de découverte, sa fonction et la place qu'il occupe au sein des productions de la fin du Néolithique.

Les croissants sont des objets plutôt rares, une quarantaine est connue à ce jour dans toute la France. On les trouve essentiellement dans deux régions, en Touraine et en Île-de-France. On les rencontre le plus souvent dans les habitats, mais ils apparaissent également en contexte minier, d'atelier de taille du silex et même sépulcral.

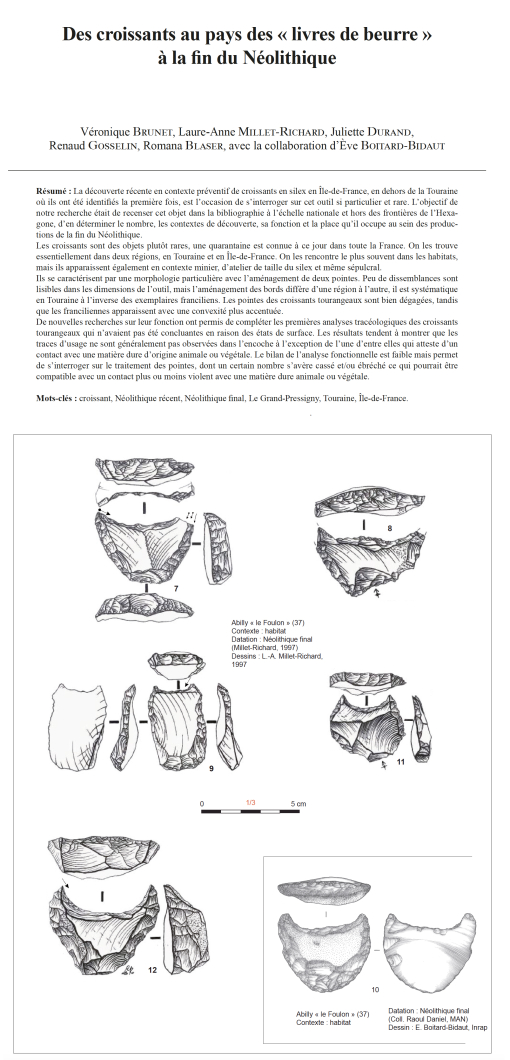

Ils se caractérisent par une morphologie particulière avec l'aménagement de deux pointes. Peu de dissemblances sont lisibles dans les dimensions de l'outil, mais l'aménagement des bords diffère d'une région à l'autre, il est systématique en Touraine à l'inverse des exemplaires franciliens. Les pointes des croissants tourangeaux sont bien dégagées, tandis que les franciliennes apparaissent avec une convexité plus accentuée.

De nouvelles recherches sur leur fonction ont permis de compléter les premières analyses tracéologiques des croissants tourangeaux qui n'avaient pas été concluantes en raison des états de surface. Les résultats tendent à montrer que les traces d'usage ne sont généralement pas observées dans l'encoche à l'exception de l'une d'entre elles qui atteste d'un contact avec une matière dure d'origine animale ou végétale. Le bilan de l'analyse fonctionnelle est faible mais permet de s'interroger sur le traitement des pointes, dont un certain nombre s'avère cassé et/ou ébréché ce qui pourrait être compatible avec un contact plus ou moins violent avec une matière dure animale ou végétale.

Mots-clés : croissant, Néolithique récent, Néolithique final, Le Grand-Pressigny, Touraine, Île-de-France.

Abstract: A recent discovery of flint croissants in a preventive excavation in Île-de-France, outside the area where they were first discovered in Touraine, provided an opportunity to investigate this rather particular artefact. A search was made in the literature published both within and outside France, in order to determine the numbers of croissants and their find contexts, as well as to examine their function and role in later Neolithic flint production.

Croissants are quite rare objects, as about forty are currently recorded for the whole of France. Occurring in two regions, Touraine and Île-de-France, they are most often found in settlements, but also appear in mining, workshop and even burial contexts.

Of the thirty or so croissants known in the Grand-Pressigny area, twenty-two were discovered in the commune of Abilly (Indre-et-Loire), thirteen of which come from excavations on the Foulon site and one other from La Madelone, about 1 km to the north-west. In the Île-de-France region, croissants are still few and far between, with six examples and only one per occupation. Two come from sites in the north of the Seine-et-Marne département, located in the river Marne valley and less than 5 km apart. There is one example in the Loiret département, another from the Val d???Oise and lastly there are two from the Yvelines.

This tool is generally made from local raw materials. The morphology is particular, due to the creation of two tangs. Although there is little difference in tool dimensions between the two regions, the shaping of the edges differs from one region to another. The edges are systematically retouched in Touraine, while this is not always the case in Île-de-France. The Touraine croissants have clearly defined tangs, whereas the Île-de-France croissants appear less concave.

While selected flakes may have been specifically produced by hard direct percussion, some flakes from the Grand-Pressigny area are derived from the preparation or maintenance of "pound of butter" (livre de beurre) cores. The croissants were most often produced along the axis of the flakes, with retouched tangs on each of the two lateral ends. The retouch was done by hard hammer. The lengths croissants vary from 32 to 65 mm in Touraine and from 25 to 90 mm in Île-de-France. In Touraine widths are between 29 and 93 mm and in Île-de-France between 33 and 146 mm. The Touraine croissants are mostly between 10 and 19 mm thick, whereas in Île-de-France thickness ranges from 6 to 23 mm.

While the croissants from Touraine and western Île-de-France can be grouped in the same family because of their similarity in shape, the eastern Île-de-France croissants are more difficult to include as they deviate from the norm. This suggests that they are probably different objects. In fact, the morphology of the croissant from Coupvray in Seine-et-Marne has little in common with the broad family of croissants. Nevertheless, it does show similarities in function with the Touraine examples, as indicated by similar use-ware flaking observed on the barbs of the tool.

The initial use-wear analyses of the Touraine croissants were not conclusive, due to the surface conditions. The new study undertaken here generally shows that no traces of use can be observed in the concavity, with one exception attesting to contact with a hard material of animal or vegetable origin. The result of the functional analysis is thus limited but does raise questions about the treatment of the tangs, some of which are broken and/or chipped, which could be compatible with more or less violent contact with a hard animal or plant material.

In the Île-de-France region, croissants are frequently associated with flaked axes. Other associated tools vary greatly from one area to another. In Touraine, fourteen different categories of tools are recorded, mainly daggers, micro-denticulates, notched side-scrapers, retouched blades, scrapers etc.

In Île-de-France, the tool categories are more numerous, with up to twenty different categories in the west and a dozen in the east. This is probably due to the context in which the tools were found, with the composition of the associated tools differing between workshops and settlements, with a majority of bifacial pieces with active cutting edges in the former and scrapers in the latter.

The croissants from Île-de-France may possibly be older than their counterparts in Touraine, since the latter are associated with occupations dated to the Final Neolithic. In Île-de-France, croissants are found in the Late Neolithic and perhaps even as early as the Middle Neolithic at Adon (Loiret).

Since only two regions have so far produced evidence for croissants, in different proportions, this raises the question of the origin of the tool type. Was it mainly produced in Touraine, spreading to Île-de-France with the Pressignian phenomenon, or the reverse from east to west?

Keywords: croissants, late Neolithic, final Neolithic, Grand-Pressigny, Touraine, Île-de-France.