- La SPF

- Réunions

- Le Bulletin de la SPF

- Organisation et comité de rédaction

- Comité de lecture (2020-2025)

- Ligne éditoriale et consignes BSPF

- Données supplémentaires

- Annoncer dans le Bulletin de la SPF

- Séances de la SPF (suppléments)

- Bulletin de la SPF 2025, tome 122

- Bulletin de la SPF 2024, tome 121

- Bulletin de la SPF 2023, tome 120

- Bulletin de la SPF 2022, tome 119

- Archives BSPF 1904-2021 en accès libre

- Publications

- Newsletter

- Boutique

Prix : 15,00 €TTC

02-2019, tome 116, 1, p. 29-39 - Pascal Foucher, Cristina San Juan-Foucher, Sébastien Villotte, Priscilla Bayle, Carole Vercoutère, Catherine Ferrier - Les vestiges humains gravettiens de la grotte de Gargas (Aventignan, France) : datations 14C AMS

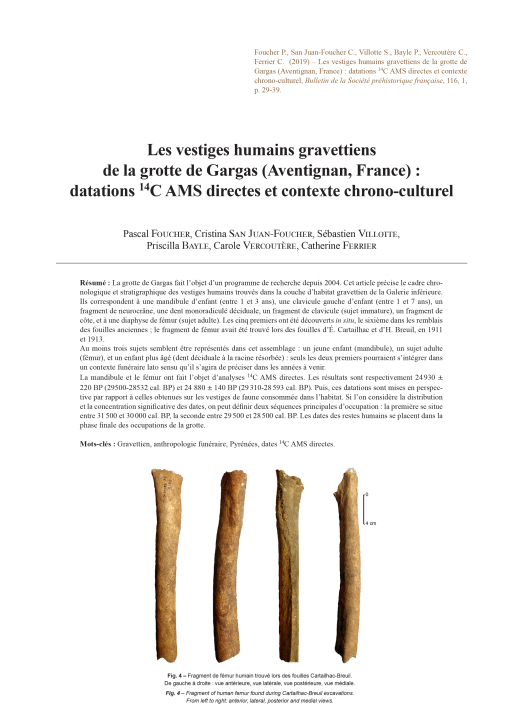

Résumé : La grotte de Gargas fait l'objet d'un programme de recherche depuis 2004. Cet article précise le cadre chronologique et stratigraphique des vestiges humains trouvés dans la couche d'habitat gravettien de la Galerie inférieure. Ils correspondent à une mandibule d'enfant (entre 1 et 3 ans), une clavicule gauche d'enfant (entre 1 et 7 ans), un fragment de neurocrâne, une dent monoradiculé déciduale, un fragment de clavicule (sujet immature), un fragment de côte, et à une diaphyse de fémur (sujet adulte). Les cinq premiers ont été découverts in situ, le sixième dans les remblais des fouilles anciennes ; le fragment de fémur avait été trouvé lors des fouilles d'É. Cartailhac et d'H. Breuil, en 1911 et 1913.

Au moins trois sujets semblent être représentés dans cet assemblage : un jeune enfant (mandibule), un sujet adulte (fémur), et un enfant plus âgé (dent déciduale à la racine résorbée) : seuls les deux premiers pourraient s'intégrer dans un contexte funéraire lato sensu qu'il s'agira de préciser dans les années à venir.

La mandibule et le fémur ont fait l'objet d'analyses 14C AMS directes. Les résultats sont respectivement 24 930 ± 220 BP (29500 28532 cal. BP) et 24 880 ± 140 BP (29 310-28 593 cal. BP). Puis, ces datations sont mises en perspective par rapport à celles obtenues sur les vestiges de faune consommée dans l'habitat. Si l'on considère la distribution et la concentration significative des dates, on peut définir deux séquences principales d'occupation : la première se situe entre 31 500 et 30 000 cal. BP, la seconde entre 29 500 et 28 500 cal. BP. Les dates des restes humains se placent dans la phase finale des occupations de la grotte.

The Gargas cave has been the subject of a research programme since 2004. This article focuses on the chronological and anthropobiological framework of the human remains found in the Gravettian habitat levels of the Lower Gallery. These remains are:

- a well-preserved fragment of a child mandible (GPA-11-Wb-646) found in the GPA sector, in Room I, close to the Great Wall of Hands. The coronoid process is missing, the lateral face of the condylar process is eroded, the gonial angle is broken, and the superficial external cortical bone of the lower margin of the symphyeal region is desquamated on ca. 20 mm. The age-at-death is estimated between 1 and 3 years, based on the degree of mineralization and eruption of the teeth. The mandible was found in the upper third of a Gravettian level. Its archaeological context consisted mainly of an accumulation of faunal remains (centimetric to decimetric fragments and small burnt elements, some of them with anthropogenic traces), and some elements of lithic industry (tools and debitage products in flint and quartzite), used pebbles and coloring materials;

- a fragment of a child left clavicle (GPA-11-Wb-610). The bone is preserved on 47 mm, from the lateral third of the insertion for the deltoid muscle to the middle of the M. pectoralis major attachment site. The breaks are smooth and the bone surface displays many impacts, probably due to carnivorous activity. The age-at-death it estimated to 1 to 7 years;

- an immature clavicle fragment (uncertain determination) (GPA-11-Wb); in any case, this small fragment does not correspond to the previous left clavicle;

- a small (36.0 mm length and 20.0 mm width) neurocranial fragment (GPO 05-K9a) found in the GPO area (corresponding to the former entrance). This fragment belongs to an adult or a subadult; ??? a first upper right deciduous incisor (GPO-07- K13b-1550). The crown is very worn and preserved only on 2 to 3 mm.

Three quarters of the root appear resorbed, indicating an age between 6 to 7 years old;

- a 42 mm long body fragment of a rib (GDI-2011 deblais) with grey sediment covering one extremity, and with some red linear traces on the surfaces. This bone was found in the GDI sector, within the dumps of previous excavations. The very ovoid and fairly thick section (7 by 11 mm) makes uncertain the attribution to the human species;

- a fragment of an adult left femoral diaphysis, preserved over 242 millimeters, found in the Cartailhac-Breuil collection of the "Institut de Paléontologie Humaine". The bone is broken proximally below the lesser trochanter and distally at the junction between the second and last third of the diaphysis. This human remain, discovered during the excavations of É. Cartailhac and H. Breuil between 1911 and 1913, was reported by Hugo Obermaier in his book L'Homme fossile and attributed to the "Aurignacien supérieur" (Gravettian), without further information.

At least three subjects are represented in this skeletal assemblage: a young child (the mandible), an adult individual (the femur), and an older child (the deciduous tooth with resorbed root): only the first two individuals were concerned by mortuary practices that have to be discussed in following studies.

The first five human remains were discovered in situ within the Gravetian sedimentary unit, which corresponds to a palimpsest of occupations. From a chrono-cultural point of view, and on the basis of a typo-technological analysis of the lithic industry (Noailles burins, Gravette and Vachons points) and bone industry (Isturitz-type assegai points and herbivore ribs decorated with notches), Gargas settlement is attributed to the Noaillian.

The mandible and the femur were directly dated (AMS C14 radiocarbon date). The results are respectively 24,930 ±220 BP (29500-28532 cal. BP) and 24,880 ±140 BP (29310-28593 cal. BP). These dates are compared with the chronological sequence obtained from C14 dates on the faunal remains. Considering the distribution and significant concentration of dates, two main periods of occupations can be identified: the first one is between 31,500 and 30,000 cal. years BP, the second between 29,500 and 28,500 cal. years BP. The direct dates of the human remains place them in the final phase of the occupation of the cave.

The presence of human remains in the Gravettian occupation levels of Gargas, at the foot of the decorated walls, brings new perspectives for studies on the relationship between mortuary practices, settlement and art. We were able to highlight in Room I, where two thirds of the handprints are concentrated, the interpenetration of a ???domestic??? and a ???symbolic??? space. The taphonomical context of the human remains, isolated and without anatomical connection, sometimes covered with a thin calcite layer, suggests surface deposits that have undergone post-depositional mechanical disturbances altering the original disposition and thus making difficult to interpret their funeral context.

Autres articles de "Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française 2019"

21-2019, tome 116, 4, p.743-774 - Christophe Croutsch, Willy Tegel, Estelle Rault — Les puits de l’ âge du Bronze du Parc d’ Activités du Pays d’Erstein (Bas-Rhin, Alsace) : des analyses dendroarchéologiques à l’ étude de l’occupation du sol

Les puits de l'âge du Bronze du Parc d'Activités du Pays d'Erstein (Bas-Rhin, Alsace) Des analyses dendroarchéologiques à l'étude de l'occupation du sol

Christophe Croutsch, Willy Tegel, Estelle Rault

Résumé : Entre 2006 et 2014, les opérations d'archéologie préventive réalisées dans le cadre du projet du Parc d'Activités du Pays d'Erstein ont permis d'explorer une superficie de 55 ha. Les décapages ont mis au jour plus de trois-cent structures datées de l'âge du Bronze : fosses, silos, vases-silos, grandes fosses polylobées associés à des puits à eau. Les occupations s'étendent du Néolithique final/Bronze ancien à l'étape moyenne du Bronze final. L'une des particularités du site est d'avoir livré des puits à eau avec des bois gorgés d'eau conservés à leur base.

Huit puits ont livré des restes de cuvelage en bois. Trois principaux types de structures ont été observés : les captages cylindriques, les cuvelages quadrangulaires en blockbau et les cuvelages assemblés avec des planches plantées verticalement.

Quatre-cent-soixante-cinq bois gorgés ont été échantillonnés et analysés. Cent-treize bois ont pu être datés. La synchronisation des séries sur les courbes régionales de référence du chêne a permis la construction de trois courbes moyennes : la première courbe a pu être calée entre 2354 et 2215 av. J.-C. ; la deuxième entre 2131 et 1571 av. J.-C. ; et la troisième courbe entre 1320 et 1002 av. J.-C. La longévité des puits est de l'ordre de quelques années à plusieurs décennies. Mais dans la plupart des cas, il s'agit de structures pérennes parfois utilisées sur plusieurs générations.

Grâce aux nombreuses dates dendrochronologiques, le site du Parc d'Activités du Pays d'Erstein offre l???occasion de suivre le rythme des occupations et des déplacements des habitats avec une résolution chronologique inhabituelle pour un site terrestre. Au cours de l???âge du Bronze, on observe une forte stabilité des modes d'occupation du sol caractérisés par la présence de petits établissements mobiles régulièrement déplacés et relocalisés à l'intérieur de leur terroir. Ce système semble bien en place dès le Bronze ancien et se maintient jusqu'au Bronze final.

Mots-clés : âge du Bronze, Alsace, puits, occupation du sol, dendrochronologie, dendrologie, roue en bois.

Abstract: Between 2006 and 2014, several preventive archaeological surveys of an area of 55 ha were carried out before the development of the Parc d???Activités du Pays d???Erstein. The excavations brought to light more than three hundred, mainly domestic, features (e.g. pits, silos, storage vessels, large pits associated with wells) dating to the Bronze Age. The excavation also revealed periods of human activity during the Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age (Late Beaker Culture/Bz A1) transition, the Middle Bronze Age (Bz A2-B1 then Bz C) and the Late Bronze Age (Bz D and Ha A2-B1).

One of the particularities of the site is the excellent preservation of wood in the waterlogged conditions of the wells. These included eight linings, built from logs or hollowed tree trunks. Construction pits used to dig the wells contained three types of well linings that reached the ground water level: tube linings using hollowed out trunk sections, vertically planted planks and chest-like well linings using timber logs. The latter construction types were found in the same pit. Three linings consisted of hollow trunks probably using old trees. The chest-like linings used logs cut in half, whole logs or planks. The planks were split out of trunks in a radial or tangential direction. Only one lining used vertically planted planks (slabs).

The exceptionally well-preserved timbers allowed sampling and analyses of 465 waterlogged wooden finds. In total 411 wood samples were anatomically identified including eight species. Oak (Quercus sp.) dominated the species assemblage, followed by maple (Acer sp.), hazel (Corylus sp.) and beech (Fagus sp.). For the purpose of dendrochronological dating only oak timbers with more than 20 tree rings were analysed and it was possible to date 113 timbers. In 48 samples the outermost ring beneath the bark (waney edge) was preserved, allowing the determination of the felling year of the used trees. Moreover, the cross dating of the 113 tree-ring width series enabled the development of three site chronologies, which could be absolutely dated based on high visual and statistical agreement with different regional oak master chronologies. The first chronology includes 12 series and covers the period 2354???2215 BC, the second is based on 40 series covering the period 2131???1571 BC, and the third with 62 series could be synchronised between 1320 and 1002 BC.

The use period of the wells varies considerably from only a few years to several decades and in the case of wells that are regularly reused the period of use could be considerably longer. For some of the wells it has been possible to estimate the minimum duration of use and in many cases, these long-lived structures were used for several generations.

Owing to the high quantity and quality of dendrochronological data, the archaeological site of the the Parc d???Activités du Pays d???Erstein offers new insights into settlement dynamics and occupation periods with an unusually precise chronological resolution for a land based site.

The first occupation phase with about twenty structures located in the north and in the middle of the excavated area dates back to the Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age. The well dating to this first phase contains timbers dating to 2231 and 2215 BC. After a hiatus of several centuries, a second settlement phase dates to between 1750 and 1715 BC, doc umented by only a few oak planks from the bottom of a well. A later settlement phase dating to between the end of the 17th century and first half of the 16th century BC is located to the north of the site where two wells were dug around 1615 BC. The few features of this phase can be attributed to Middle Bronze B1. For the following phase of the Middle Bronze Age C2 only a few features were found and excavated, but no wells are dated to this phase.

The settlement dating to the second half of the 13th century and the first half of the 12th century BC has several poles. Three wooden well linings date to between 1241 and 1208 BC and one earlier well was restored during this period (1237 BC). About ten features were excavated from this 75 years long phase of the Late Bronze Age.

The last phase covers the 11th century and the first half of the 10th century BC with features found all over the excavation area. Four wells date to this phase covering an 80-year period from 1078 to 1002 BC and were probably in use from the last quarter of the 11th century up until the first half of the 11th century BC. The 70 or so domestic features dating to the middle of the Late Bronze Age indicate a densely occupied settlement.

During the Bronze Age, the presence of small mobile settlements or homesteads that regularly moved and relocated within their territory, characterises stable land use patterns. This system seems, as the example of the Parc d'Activités du Pays d'Erstein shows, to be in place probably from the Early Bronze Age and maintained until the Late Bronze Age.

Keywords: Bronze Age, Alsace, well, land use, dendrochronology, dendrology, cartwheel.

20-2019, tome 116, 4, p.725-742 - Audrey Blanchard, Annabelle Dufournet, Geoffrey Leblé, avec la collaboration de Mohamed Sassi et Alexandre Polinski — Un ensemble funéraire du Campaniforme / Bronze ancien : le site des « Touches » à Plénée-Jugon (Côtes

Un ensemble funéraire du Campaniforme / Bronze ancien

Le site des « Touches » à Plénée-Jugon (Côtes-d'Armor)

Audrey Blanchard, Annabelle Dufournet, Geoffrey Leblé,

avec la collaboration de Mohamed Sassi et Alexandre Polinski

Résumé : La fouille menée sur le site des « Touches » à Plénée-Jugon (Côtes-d'Armor) au printemps 2015 a permis de mettre au jour un ensemble funéraire composé de 13 sépultures. Situé sur un replat en milieu de pente, il se développe sur 170 m² en limite orientale de l'emprise. Les structures funéraires sont des fosses de formes quadrangulaires aux angles arrondis, orientées nord-ouest/sud-est ou ouest-sud-ouest/est-nord-est. Si aucun reste osseux n'est conservé sur ce terrain peu propice, les nombreuses pierres découvertes dans les comblements permettent de proposer l'existence de plusieurs dispositifs : coffre de bois mobile, planches, coffrage, système de marquage au sol. Le mobilier est rare et majoritairement en position secondaire. Un récipient céramique atteste d'au moins un geste intentionnel de dépôt asso cié à une sépulture. Les datations par le radiocarbone (oscillant de 2600 à 1600 cal BC) tout comme les caractéristiques typo technologique du mobilier ne permettent qu'une large attribution de cet ensemble au Campaniforme et/ou à l'âge du Bronze ancien.

Mots-clés : Campaniforme, âge du Bronze ancien, ensemble funéraire, Bretagne, architectures funéraires.

Abstract: The site of « Les Touches » is located to the north-west of Plénée-Jugon (Côtes-d'Armor), about 30 km south-east of Saint-Brieuc. The archaeological excavation was carried out in spring 2015 before the realignment of the RD59 by the Conseil Général des Côtes-d'Armor. The excavation, which covered an area of 9 000 m², was cen tered on the late prehistoric features that were discovered south of the road project during trial trenches carried out by A.-L. Hamon in 2013. The site dates to the second half of the Late Iron Age and to Early Antiquity. It also includes a small funerary group dating to the beginning of the Metal Ages.

The funerary group is located on the eastern edge of the excavation in a small flat area in the middle of a slope, approximately 300 m to the northeast of an Early Bronze Age settlement identified during a previous operation. At an altitude of 77 m NGF, it overlooks the Quiloury Valley. It consists of 13 funerary features in an area of approximately 170 m². As it stands, the extent of this group remains unknown; it is possible that it continues beyond the boundaries of the excavation. A pit (FS) and several post holes (PO) were found in the vicinity of the burials (SP). The pit FS1639, con taining an arciform cord urn from the Early Bronze Age 2, could be linked to the small funerary complex as it cuts the tomb SP1124 . The post holes did not provide any datable material or elements linking them to the burials. Similarly, no ditches or mounds were identified. More broadly, no other Early Bronze Age feature was found on the excavation.

The burials are housed in quadrangular pits with rounded corners. Their orientations vary from north-west/south-east to west-south-west/east-north-east. Their dimensions vary from 1.36 m x 0.76 m for the smallest (SP1120) to 3.64 m x 1.90 m for the largest (SP1121). The cuts have a rounded profile with a flat bottom that is more or less even and vertical or subvertical sides. The burials are 0.17 m (SP1128) to 0.62 m deep (SP1121). However, none of the skeletal material is preserved, which is typical for this northern part of Brittany with its acidic soils. The funerary architectures that include stone and wood are diverse. Micromorphological analyses also suggest the use of earth. There are several types of burial: mobile perishable material containers set by stones in SP1119 and SP1120, mobile perishable material containers made of wood lined with clay and set by stones for SP1122 and SP1126, wooden or stone frame for SP1115 and SP1139 or a funerary chamber for SP1121. Other constructions, notably in stone, mark the burials (piling of blocks on the surface, possible small cairns, etc.).

Funerary goods are rare. A quadrangular container found in SP1139 is the only evidence of an intentional deposit. The artefacts consist of small pottery and lithic fragments found in secondary deposition contexts. The finds date to the Bell Beaker period and/or the Early Bronze Age. Thirteen radiocarbon dates from eleven features range from 2600 to 1600 cal BC. However, these dates can be brought into question as the charcoal samples come from secondary deposition contexts. It seems that the earliest burials date to the end of the Bell Beaker period and the group developed during the Early Bronze Age.

Small funerary groups dating to the Early Bronze Age such as 'Les Touches' are rare in Brittany and the Armorican Massif. This area is better known for its tumuli, built using earth and stone that cover one or several burials. They are sometimes organized into funerary groups directly linked to a family farm or a village. It is therefore tempting to link the site of 'Les Touches' with the settlement discovered at the Gouviard quarry located 300 m to the southeast. The dates obtained on the latter, from 2290-2051 cal BC, are comparable to those proposed for the funerary complex.

Such burial groups are not, however, unprecedented for the Bell Beaker period/Early Bronze Age, as similar sites have been documented in eastern and southern France. 'Les Touches' contributes to a better perception of the funerary prac tices of the end of the Neolithic and the beginning of the Bronze Age in the Armorican Massif.

Keywords: Bell-Beaker, Bronze Age, grave, funeral complex, Bretagne, funerary architecture.

19-2019, tome 116, 4, p.705-724 - Bruno Boulestin — Faut-il en finir avec la sépulture collective (et sinon qu’en faire) ?

Faut-il en finir avec la sépulture collective (et sinon qu'en faire) ?

Bruno Boulestin

Résumé : Depuis les années 1960, l'appellation de sépulture collective est d'un emploi commun en archéologie. Elle a pourtant suscité de nombreuses discussions, notamment parce qu'elle est aussi utilisée pour désigner des structures et des fonctionnements observés en ethnographie et qu'il existe de ce fait une tendance permanente pour lui accorder une signification sociale de plus en plus grande. Cela amène à se poser deux questions : pouvons-nous conserver sous sa forme actuelle la terminologie employée ou devons-nous la modifier ? Et, surtout, pouvons-nous continuer à utiliser le même concept à la fois en archéologie et en ethnologie, et si oui à quelles conditions ?

En définissant correctement l'unité analytique de référence qu'est la sépulture, puis en examinant les différentes manières possibles d'y réunir des morts, on peut finalement montrer que la terminologie française actuelle se rapportant à la sépulture collective est tout à fait opérationnelle en archéologie comme en ethnologie et est transposable d'une discipline à une autre dès lors que l'on évite absolument d'intégrer une fonction sociale dans les définitions. On peut toutefois apporter quelques ajustements à ces dernières pour lever certaines ambiguïtés et en assurer la cohérence, ainsi que quelques précisions d'utilisation.

Par ailleurs, l'opposition classique entre la sépulture multiple et la sépulture collective apparaît fondamentale, parce qu'elle permet de dégager un comportement mortuaire particulier et de conjecturer que toutes les sépultures collectives archéologiques ont été établies pour réunir des individus liés par la parenté.

Mots-clés : sépulture collective, sépulture multiple, sépulture plurielle, rassemblement des morts, parenté, terminologie.

Abstract: The expression "collective burial" has been in use among archaeologists since the 19th century, but has become increasingly successful particularly from the 1960's, along with the development in France of the research on Neolithic funerary ensembles and of funerary archaeology. Soon enough, parallel questioning about what was (or what should be) a collective burial arose, and its definition has evolved and been discussed many a time. In particular, since archaeologists make use of that term to describe also by analogy features and operations observed in ethnography, they tend to embed more and more functional aspects in its definition: at the beginning, "collective" was a purely descriptive term, later it referred to a functioning, and finally was recently regarded as describing a social function. This leads to two questions: should the terminology in use be kept in its present form or does it need to be modified? And above all, can the same concept be used in both archaeology and ethnology, and if so, under which conditions?

Answers to these questions begin with an accurate definition of a reference analytical unit. Obviously that unit is the burial, though it is necessary to specify at first that it corresponds always to a volume, and then that this is the smallest possible and non-movable volume (in other words an immovable asset) containing the body. On this basis, one can generally establish that there are only two possible main ways to group the dead, either by gathering the burials in a larger volume or in the same space, or by gathering the dead themselves in the same burial. The latter choice matches exactly the French archaeological definition of the plural burial (a burial containing at least two people), and it is safe to say that this definition can be applied to ethnology as well. Identifying a plural burial in archaeology is not always obvious, since finding two dead people in the same place is not enough evidence. One has to assume that the space in which they were placed was intended as a single volume, and that they were deposited during a unitary use (in other words during a same phase of use), hence conveying the will to bring them together. If there is any doubt regarding one or the other aspect, it becomes impossible to speak of plural burial, and one can only mention a set of individuals. Moreover, specifying that space as a burial requires another condition: there must be enough arguments to think that the gathering of the dead results indeed from a funerary practice. If not, the term gathering (of individuals) can be used, whereas the terms deposit or deposition, which must be used with great care, should be avoided.

There are many possible ways to classify the types of plural burials encountered in ethnohistory; the most relevant though is to divide them into two main categories: those that are used only once, and those that are used several times. The former perfectly match the French archaeological definition of a multiple burial, whereas the latter tally exactly with the collective burials, although in this case precisely it is necessary to slightly adjust the classic definition in order to clarify some ambiguities. This is also the occasion to embed in the definition the archaeologically imperative notion of demonstrability. Consequently, the multiple burial can be defined as a burial gathering at least two persons and for which it can be demonstrated that the dead were all deposited at the same moment; a collective burial is a burial with at least two individuals, for which it can be proved, on the contrary, that the dead were not deposited on one single occasion. It can be more or less difficult in archaeology to make the distinction between multiple and collective, and materially interpreting the field data is always necessary. Whenever it is not possible to do so, or when it is impossible to decide, one must stick to the expression ???plural burial???.

Finally, the current French terminology regarding the collective burial is perfectly functional, provided a few precau tions are taken: 1) the reference analytical space must be perfectly identified; 2) the concepts behind each term, and what they imply practically, must be clearly specified; 3) a social function must never be included in the definitions. With some adjustments and some specifications regarding the use of these definitions, we can totally go on using this terminology, all the more so since it can be transposed from one field to the other, and thus used both in archaeology and ethnology. Moreover, the distinction between multiple burial and collective burial is fundamental, since it enables us to infer a specific mortuary behaviour. Whereas the multiple burials are created to gather people having various relationships with one another, and who necessarily died or were killed on this occasion, the collective burials are always established to gather related people, even though some of them are not dead yet. There is no known exception to this reason in ethnology, so it seems safe to assume that all the archaeological collective burials were created to gather family-related people.

From this point, the conceptual and terminological basis at our disposal is thus perfectly fit to try and go further in our interpretations. In the future, it will be necessary to try and understand why in some societies graves are gathered in cemeteries, whereas in others it is the dead that are gathered in the graves. We will also have to attempt to explain the many varieties of collective burials observed in ethnology, and if possible to match them with those identified in archaeology.

Keywords: collective burial, multiple burial, plural burial, gathering of dead, kinship, terminology.

18-2019, tome 116, 4, p.681-704 - Robin Brigand, Yves Billaud — L’habitat Néolithique final de Beau Phare à Aiguebelette-le-Lac (Savoie) : nouvelles approches méthodologiques de la planimétrie d’un village littoral de l’arc alpin

L'habitat Néolithique final de Beau Phare à Aiguebelette-le-Lac (Savoie)

Nouvelles approches méthodologiques de la planimétrie d'un village littoral de l'arc alpin

Robin Brigand, Yves Billaud

Résumé : Le site d'Aiguebelette-le-Lac/Beau-Phare se trouve dans la partie méridionale du lac, sur une avancée de la plateforme littorale formant une presqu'île étroite. A faible profondeur, la station est repérée dès 1863 et fait l'objet de ramassages jusqu'au début du XXe siècle. Dans le cadre de l'opération de suivi dirigée par Y. Billaud (2015-2018) suite à l'inscription de la station sur la liste du Patrimoine mondial de l'Unesco (2011), un bilan sanitaire et documentaire du site a été réalisé en 2016. La synthèse des données issues des opérations de R. Laurent (1971) et d'A. Marguet (1983 et 1998), couplée à une courte mission de terrain a permis de progresser dans la connaissance du site. Afin de poursuivre l'exploration de ce site et documenter, pour la première fois en Savoie, le plan d'un village littoral du Néolithique final, une opération de prospection subaquatique s'est déroulée en 2018. L'objectif de cette campagne a été de réaliser un relevé du champ de pieux afin de disposer d'une vue générale de la structuration de l'habitat. L'originalité de ce site palafittique consiste en un chemin d'accès barré d'au moins trois palissades. Le plan villageois, très régulier, s'organise selon une orientation préférentielle à la perpendiculaire de l'axe du chemin, tout particulièrement pour le secteur est où quatre bâtiments de 5 × 10 m environ sont accolés par leurs murs gouttereaux. A l'ouest du chemin, au moins deux bâtiments se distinguent nettement : un premier, le long du chemin, fait face à l'entrée ; un second se situe entre deux palissades. En l'état actuel des recherches, près de douze pieux datés par dendrochronologie permettent une première esquisse de l'occupation du village avec une date en -2693 obtenue sur deux pieux en sapin disposés de part et d'autre de la palissade interne. Quatre bois de cette dernière ont été abattus en -2684. Enfin plusieurs dates obtenues sur les alignements de pieux au sud du site archéologique plaident pour une construction du chemin d'accès en -2672.

Mots-clés : Néolithique final, station littorale, Aiguebelette, étude spatiale, Unesco.

Abstract: The site of Aiguebelette-le-Lac / Beau-Phare is one of two final Neolithic settlement sites on Lake Aiguebelette. It is located in the southern part of the lake, on an extension of the shore platform, which forms a small peninsula to the north of Lépin Castel. Situated in shallow water (between 0.5 and 2 m in depth), the site was first identified in 1863 and was a focus for artefact collecting until the beginning of the 20th century. Following the inclusion of the site on the Unesco list of World Heritage Sites in 2011, Y. Billaud undertook the direction of a monitoring project, which included a condition assessment and bibliographic survey of the site conducted in 2016. A review of data produced by R. Laurent (1971) and A. Marguet (1983 and 1998), coupled with a short fieldwork campaign, significantly advanced our knowledge of the site. The extent of the site was established and an entrance path, which traversed three palisades, was identified and mapped. An area of 100 m² at the centre of the site was surveyed, bringing the total area recorded to 230 m².

As part of the continuing exploration of the site, an underwater survey was carried out in 2018. The aim of this campaign was to plot the surviving timber piles in order to obtain an overview of the layout of the village. Prior to the recording of the piles, a 3600 m² grid was laid out. Depending on the area of the site and the density of piles, each 10x10 m square was subdivided into four intermediate units, each measuring 25 m². Some 1401 piles were plotted within an area 2600 m², which brings the number of recorded piles to 1670 out of a total of about 3000 for the entire site. The survey report throws considerable new light on the layout of the site. The gently curving access trackway crosses the village and extends as far as the northern extremity of the peninsula. It is formed by two parallel rows of piles, positioned some 1.6 to 2 m apart. The line of the path has been traced over a distance of about 90 m. Located to the east of the central axis of the peninsula, the trackway slopes gently upwards (0.7%) as far as the inner palisade before rising more steeply at the entrance to the village. It is formed of almost 290 piles, which are predominantly small in diameter and protrude only slightly above the sediments. The most evident entrance to the village is located on the axis of this trackway. It is formed of two rows of contiguous piles, which form a narrow bottleneck measuring less than 1 m in width. Some dendrochronological dates suggest it was built with trees felled in -2672.

At least three palisades have been identified, representing several phases of building and re-building. The outer palisade forms the first enclosing element, which would have been encountered by approaching the site from the south. On the western side of the trackway, a single line of posts can be observed while to the east three roughly parallel lines are visible. The middle palisade features a marked dissymmetry between the sections to the east and west of the trackway. On the western side, it is composed of 24 piles spread out over a length of about 25 m. To the east of the trackway, its morphology is similar over a length of about 7 m: it is composed of densely spaced piles, which are medium size and very eroded. The line of the inner palisade is difficult to discern apart from an initial section at the east and a second section corresponding to the topographical ???centre??? the 1998 survey. Four piles belong to trees felled in -2684. The two segments of this palisade are typologically similar to the middle palisade: they are composed of piles of various dimensions, but always quite small, which are positioned very close together (less than about 0,5 m apart). The easternmost section is interesting because it does not form a straight line but instead but appears to form a dog-leg to the south-west where we observe five aligned piles. At this point, the gap in the palisade resembles an entrance and is precisely located in the continuity of a south-west/north-east orientated circulation area.

The layout of the village is very regular with most buildings orientated perpendicularly to the axis of the pathway, particularly in the eastern sector. To the west of the access path, we can distinguish four buildings. The westernmost of these is perhaps the most easily identifiable; the small building, measuring 4 m by 6 m and orientated east/west, is composed of relatively large piles. The roof and foundation piles, intended to support the roof ridge and sill beams, are generally over 12 cm in diameter and, based on field observations and the heights of the surviving cones, appear to be of hard wood. Located a short distance to the north-east, we observe a second similar building. Also orientated east/west, this small building (4 x 7 m) is formed of three rows of posts; it too is supported on relatively large piles.

An enigmatic building lies in the southern part of the village, between the inner and middle palisades. Measuring about 5 by 8 m, it is directly adjacent to the pathway and the three rows of posts that delimit it are orientated north/south. The posts located at the extremities of the three rows are paired and have a diameter of more than 14 cm. The small number of piles to support the sill beams, and the absence of posts to support the cross-pieces, suggest that this building lacked a raised floor, or indeed any type of floor, and may have been open-sided. Its dimensions, its location adjacent to the pathway and its architecture do not suggest a domestic structure. While its exact function remains unknown, we could hypothesise that it acted as an area for the storage and drying of timber, or perhaps as a workshop or warehouse.

The largest building in the western sector is located at the centre of the site, facing the entrance within a space marked by a very high concentration of piles. Measuring about 5 by 10 m, this building is formed of three north-south orien tated rows of piles. The eastern and western rows are formed of six groups of posts that delimit five bays. The posts are generally quite substantial (between 17 and 20 cm) and are of hardwood with very well-preserved erosion cones. At the centre of the structure, the row of posts intended to support the roof ridge is clearly identifiable, particularly in the southern part of the building where they are arranged in pairs.

In contrast to the central building, the roof ridges of the other buildings in the sector are orientated perpendicular to the axis of the pathway. The buildings are thus arranged adjacent to each other with their long sides orientated east-west thereby reducing their exposure to the prevailing wind which blows down the Epine Mountain. Nine rows of piles, positioned 1.5 to 2.5 m apart, are visible and their high density probably reflects the permanence of occupation at this spot, with considerable evidence for repairs and extensions. The architectural reconstruction of these buildings is somewhat trickier. The traditional widespread model of buildings composed of three rows of weight-bearing posts would allow us to envisage three buildings measuring about 4 by 12 m.

For the first time in Savoie and Haute Savoie, we have been able to obtain the partial plan of a lakeside village dating to the third millennium BCE. The extensive topographical survey covering an area of 2500 m² has yielded concrete evidence regarding the organization of the village and the structuring of its principal constituent planimetric elements. The unique and rich nature of the site stems from its probable short duration, which allows us to identify the general layout of the habitation areas and storage areas.

Keywords: Late Neolithic, pile dwelling settlement, Aiguebelette, spatial analysis, Unesco.

17-2019, tome 116, 4, p.657-680 - Solène Denis — Perspectives sur l’étude des productions lithiques simples au Néolithique : le cas de la culture Blicquy/Villeneuve-Saint-Germain par le prisme du site de Vasseny (Aisne)

Perspectives sur l'étude des productions lithiques simples au Néolithique

Le cas de la culture Blicquy/Villeneuve-Saint-Germain par le prisme du site de Vasseny (Aisne)

Solène Denis

Résumé : Le site de Vasseny (Aisne) a livré un petit corpus lithique attribué au Blicquy/Villeneuve-Saint-Germain qui se prêtait bien au développement d'une méthode d'étude fine sur les productions simples. Le statut de ces productions reste mal défini à ce jour, à la fois dans leur nature et leurs modalités de production. Ainsi, c'est le niveau de savoir-faire même des tailleurs qui reste à l'heure actuelle discuté. Pourtant, l'implication anthropologique est importante pour la restitution et l'interprétation de l'organisation des productions des supports de l'outillage Blicquy/Villeneuve-Saint-Germain. En l'état actuel des données, une forte variabilité semble transparaître à travers l'étude de ces productions simples. Celles-ci, sous réserve d'une stabilisation de la méthode d'étude couplée à une multiplication des analyses, pourraient contribuer à distinguer des sous-groupes chronologiques ou identitaires en surimposition aux différentes traditions techniques repérées pour la production laminaire des populations Blicquy/Villeneuve-Saint-Germain.

Mots-clés : Néolithique ancien, industrie lithique, Nord de la France, Belgique, productions simples, culture Blicquy/Villeneuve-Saint-Germain.

Abstract: The site of Vasseny 'Dessus des Groins', located in the Aisne, is a small occupation dated to the end of the early Neolithic, Blicquy/Villeneuve-Saint-Germain culture. This culture represents the final phase of the Danubian col onisation in northern France and Belgium. At least three farmsteads were discovered on the site and 1800 flints, which form a small assemblage suitable for the study of so-called simple productions. Indeed, the status of these productions remains unclear, both their nature and the modalities of their production. Estimating the level of expertise needed to produce these flints is particularly important in this context. Uncertainties reside in the existence of very small facetted pieces in the BQY/VSG assemblages, interpreted as cores or tools according to different scholars. Furthermore, the debitage can look intentionally 'neglected' due to the simple multidirectional operations or the use of successive unipolar sequences. More recently, work conducted by Miguel Biard and Caroline Riche (Inrap) has focused on the use of flint hammerstones to produce flakes. These tools leave clumsy marks that are sometimes interpreted as maladroitness. However, the authors argue that the technical knowledge of the knappers is less rudimentary than previously thought, even though the discussion is ongoing. The anthropological implication is in this case important for the restitution and the interpretation how the Blicquy/Villeneuve-Saint-Germain production was organised.

Furthermore, Blicquy/Villeneuve-Saint-Germain's lithic production is based on a dual organisation involving blade production on the one hand and 'simple' productions on the other. This raises the question of the status of knappers in charge of these productions. Indeed, does this duality opposing laminar productions / simple productions reflect the blade knappers autonomy regarding the production of the supports of lithic tools? This disconnection between 'complex' productions requiring high levels of skill and a certain degree of artisanal specialization and domestic simple productions seems to be a model that finds success during the Middle Neolithic.

The detailed study presented here includes the development of a method that highlights the objectives and the modalities of these productions. This method uses two main elements: morphometric analysis and diacritical sketches. The morphometric analysis of the flake tools and negatives of removal of cores and facetted pieces involves comparing the dimensions of the tools to the removal negatives, with the result of several facetted pieces being isolated as it was not possible to provide the corresponding sized flakes to the flake tools. It contributes to identify two objectives of these productions. Furthermore, many of these facetted pieces bear use marks. The more marks they have, the less likely they are able to produce flakes to the needed size. Diacritical sketches were also made of the flake tools, cores and facetted pieces. This has demonstrated that the modality of production is mainly based on successive sequences of unipolar debitage. To sum up, this study has identified two simple productions. One is a flake production and the other is a facetted tool production. These two productions can be autonomous or integrated. They use a hard hammer stone and the chaînes opératoires are simple without any predetermination.

The discussion integrates comparisons with other Blicquy/Villeneuve-Saint-Germain sites where detailed studies of simple productions have been conducted. First, it must be underlined that few are available and mostly linked to the work of the Programme Collectif de Recherche 'Les caractéristiques technotypologiques et fonctionnelles du débitage d'éclat au VSG. Le cas et la place des sites hauts-normands dans le nord de la France (The techno-typological and functional characteristics of VSG knapping. The case and place of Upper Normandy sites in northern France)', led by Caroline Riche (Inrap-UMR 7055). Firstly, the comparisons suggest that the simple productions are not homogenous within the geographical area corresponding to Blicquy/Villeneuve-Saint-Germain culture. For example, in Upper-Normandy, the facetted tool production does not exist. On the contrary, laminar flake production has not been previously identified on sites in the Paris Basin or in Belgium. For the latter, the production of 'pseudo-fries' on edge flakes identified in the west part of Belgium seems specific to this region. Therefore, the nature of these simple productions seems to be different, depending on geographical and probably environmental contexts. Moreover, the operating mode of production varies within the cultural area. If recent studies have demonstrated the predominance of a unipolar method, others show a bipolar or a multidirectional organisation. Further studies that include diacritical sketches and quantification of the main patterns would in the future lead to a better overview of this possible heterogeneity of the debitage. Similarly, several studies have demonstrated the use of flint hammerstones on Upper-Normandy sites. However, this is probably not the case on every site, as it would depend on the environment and the access to flint raw materials. Continuing experimentation would create a referential for both types of mineral percussion, flint and stone. A detailed comparison of marks, including quantitative data on the frequency of the different discriminant characters, would allow a re-examination of the different archaeological series to shed light on this question and that, which underlies the level of expertise of the knappers. The study of these simple productions would benefit from a uniform method with multiple analyses in order to distinguish chronological or identity subgroups superimposed on the different technical traditions observed for the laminar production of the Blicquy/Villeneuve-Saint-Germain populations.

Keywords: Early Neolithic, lithic industry, northern France and Belgium, simple productions, Blicquy/Villeneuve- Saint-Germain culture.

16-2019, tome 116, 4, p.615-656 - Gregor Marchand, Anaïs Henin, Jorge Calvo Gomez, David Cuenca Solana, Diana Nukushina — Le macro-outillage en pierre du Mésolithique atlantique : un référentiel bien daté sur l’habitat littoral de Beg-er-Vil (Quiberon, M

Le macro-outillage en pierre du Mésolithique atlantique

Un référentiel bien daté sur l???habitat littoral de Beg-er-Vil (Quiberon, Morbihan)

Grégor Marchand, Jorge Calvo Gomez, David Cuenca Solana, Anaïs Henin, Diana Nukushina

Résumé : Les macro-outils sont très peu décrits pour les industries lithiques mésolithiques du territoire français, malgré leur omniprésence dans les habitats. L'habitat côtier de Beg-er-Vil (Quiberon, Morbihan) fouillé entre 2012 et 2018 est une référence particulièrement cohérente d'un point de vue chronologique et stratigraphique pour le septième millénaire avant notre ère. Elle autorise une relecture des autres assemblages lithiques du Mésolithique atlantique, mais également des comparaisons avec les macro-outils du Néolithique récemment étudiés dans la région. Pour un total de 947 objets massifs inventoriés, émerge une série de 130 outils, dont les traces visibles à l'oeil nu ne font aucun doute et 23 outils hypothétiques nécessitant des analyses plus approfondies pour déterminer s'il s'agit de traces d'usage ou non. Neuf types d'outils ont été dégagés, hors fragments, tous divisés en un ou plusieurs sous-types. Le macro-outillage de Beg-er-Vil est très largement dominé par les percuteurs, engagés à l'évidence dans des débitages de matières minérales, mais aussi peut-être dans un concassage de matières dures animales. Suivent en nombre les galets utilisés en pièces intermédiaires très fortement percutées dans un axe longitudinal. Cet article amène à s'interroger sur l'indigence des outils massifs dans le Mésolithique de l'ouest de la France, alors que les ressources minérales adéquates sont particulièrement abondantes sur les estrans. On ne peut plus guère se réfugier derrière de possibles basculement fonctionnels vers d'autres matériaux, puisque les matières animales, bois, os ou coquilles, ne prennent pas le relai, sinon pour fournir des pioches en bois de cerf (à Téviec et Hoedic). Une large comparaison est effectuée avec d'autres zones d'Europe atlantique, à l'évidence mieux pourvues. Les enseignements en termes d'identité technique comme en termes fonctionnels peuvent en être tirés.

Mots-clés : Mésolithique, macro-outils, Bretagne, Second Mésolithique.

Abstract: Ground stone tools are rarely described for the mesolithic lithic industries of the French territory, despite their omnipresence in the dwellings. Yet elsewhere in Atlantic Europe, pebble tools sometimes play a major role in defining cultural entities, in Scotland with the Obanian, in northern Spain with the Asturian and in Portugal with the Mirian.

This obvious lack of interest in mesolithic macro-tools deprives us of crucial information on technical phylums that are evolving at a different rate from other techniques. What are the standards and practices of use of these tools compared to other material culture ranges? How have they been disseminated in the landscapes through individual or collective mobility practices? What "stylistic territories" do they help us to draw? How can we think of their very slow morpho logical evolution over time in relation to other tools? Macro-tools thus hold a particular potential for action on matter, different from other tools; discussing their uses or, unlike their non-use, thinking about human engagement with the physical world and seeking a key to understanding their being in the world.

The coastal habitat of Beg-er-Vil (Quiberon, Morbihan) excavated between 2012 and 2018 is a particularly coherent reference from a chronological and stratigraphic point of view for the seventh millennium BC. It allows a re-reading of other lithic assemblages of the Atlantic Mesolithic, but also comparisons with the Neolithic ground stone tools recently studied in the region. This coastal position has at least four implications for the availability and use of these tools: 1/ abundance of raw materials on the foreshores, 2/ exploitation of two very different ecosystems (maritime and continental), 3/ very diversified domestic activities on the habitat, 4/ need for tools to dig pits. The distribution of tools on site and the study of structures do not make it possible to highlight specific areas of activity within the habitat.

For a total of 947 massive objects inventoried, a series of 130 tools emerged, whose traces visible to the naked eye are beyond doubt and 23 hypothetical tools requiring further analysis to determine whether they have use-wear or not. There are also 470 fragments of pebbles used. The classification of the ground stone tools was based on specific criteria, the first being the type of traces visible on the surfaces, voluntary or involuntary removal, and finally the fragmentation processes in use. Nine types of tools were identified, excluding fragments, all divided into one or more subtypes. The hammers obviously dominate (64%). The intermediate elements are 8% of the entire tools, to which 54 fragments must be added and probably many longitudinally fragment. In all these cases, it should be noted that the stigma of use is relatively undeveloped when compared with equivalent Neolithic tools. There are only four tools more involved than the others: a circular hammer (type A5), two chopping-tools (D2) and a peak (D3). Concerning the types of rocks used, two of them differ considerably from the corpus, quartz for mainly active tools, as well as granite for the largest objects, whether passive or not.

This article raises questions about the paucity of ground stone tools in the Mesolithic period in western France, while suitable mineral resources are particularly abundant on foreshores. The lithic assemblages of the Early Mesolithic show a slightly broader register than those of the Late Mesolithic, all things considered. Finally, a broad comparison is made with other areas of Atlantic Europe (France, Spain, Portugal, Scotland), which are obviously better equipped. The paucity of mesolithic macro-tools in Atlantic France reflects a general organization of technical systems that do not use massive tools to interact with the rest of the physical world. It is no longer possible to take refuge behind possible functional shifts to other materials, since animal materials, antlers, bones or shells, do not take over, except to provide deer antler picks (in Téviec and Hoedic).

This first classification approach was intended to put a spotlight on a part of the mesolithic technical system that is usually left in the shadows. Our approach was intended to be functional, lato sensu, i.e. the representation of this range of tools can only be judged by integrating all the activities and functions that can be detected in the habitat, by examining combustion structures, cut tools, or organic remains. It is obvious that experimentation is now essential to determine the functions of these tools on central mass, which are not very well transformed.

Examining the technical transfers from generation to generation is difficult for the period preceding the Mesolithic. Indeed, there is still very little to say about the Upper and Late Paleolithic of Western France, especially since its maritime declination is currently inaccessible. With regard to the transformations during the Holocene, we thought we saw a possible regression of typological diversity during the Mesolithic period in Atlantic France, but we must remain very cautious due to the lack of sufficient lithic assemblages. It will be much less so if we talk about the real break with the Neolithic from the beginning, whether in the West or more generally in the North of France. New functions and much less collective mobility explain this major contrast in the use of macro-tools, but this break must also be placed in an ontological register.

The paucity of mesolithic macro-tools in Atlantic France reflects a general organization of technical systems that do not use massive tools to interact with the rest of the physical world. This absence is a cultural choice; it also reflects a discreet, obviously resilient human imprint, a way of being in the world that shapes subsequent practices.

Keywords: Mesolithic, Late Mesolithic, ground stone tools, Brittany.

15-2019, tome 116, 3, p.539-560 - Baptiste Pradier, Aung Aung Kyaw, Tin Tin Win, Anna Willis, Aude Favereau, Frédérique Valentin, T. O. Pryce — Pratiques funéraires et dynamique spatiale à Oakaie 1, une nécropole à la transition du Néolithique à l’Âge du

Pratiques funéraires et dynamique spatiale à Oakaie 1, une nécropole à la transition du Néolithique à l'Âge du Bronze au Myanmar (Birmanie) / Funerary practices and spatial dynamic at Oakaie 1, a burial ground at the transition of the Neolithic and Bronze Age in Myanmar (Burma)

Baptiste Pradier, Aung Aung Kyaw, Tin Tin Win, Anna Willis, Aude Favereau, Frédérique Valentin, T. O. Pryce

Résumé : En Asie du Sud-Est, la fin de la préhistoire - de l'apparition de l'agriculture à la naissance de proto-États - ne dure que de 1500 à 2000 ans. Les cimetières sont des sites essentiels pour comprendre ces changements marqués par des influences culturelles indiennes et chinoises. Le Myanmar est le seul pays d'Asie du Sud-Est avec lequel ces pays partagent une frontière terrestre. Les données archéologiques nouvellement acquises pour le Myanmar permettent d'éclairer cette période charnière. Cet article présente les résultats de l'étude de la nécropole d'Oakaie 1 (région de Sagaing), fouillée durant deux saisons entre 2014 et 2015 dans le cadre de la Mission Archéologique Française au Myanmar (MAFM). La nécropole est datée entre la fin du Néolithique et le début de l'âge du Bronze. Les 55 sépultures et 57 inhumés mis au jour permettent d'analyser l'évolution des pratiques funéraires pendant plusieurs siècles. L'organisation de l'espace sépulcral est particulière. Les fosses, organisées en rangées sont distribuées selon deux grandes orientations, N-S et NNO-SSE. Les inhumations sont individuelles ou plurielles (9 cas) et, dans un cas, un chien a été inhumé avec des humains. L'analyse taphonomique suggère l'usage de contenants périssables larges ou étroits, avec des bords montants, probablement des troncs d'arbres évidés. Les biens funéraires les plus communs sont des céramiques généralement placées près des membres inférieurs ou dans le comblement de la fosse. Des éléments de parure (perles en coquillages et en pierre, bracelets en pierre polie et en matière dure animale) étaient aussi associés aux défunts, tandis qu'une unique sépulture a fourni un objet en métal (une hache en bronze). L'usage croisé de critères variés, dont l'organisation spatiale de la nécropole, les recoupements de sépultures, les pratiques funéraires et le mobilier déposé auprès des défunts a permis d'établir que la nécropole a fonctionné durant trois phases. La première est caractérisée par 20 inhumations orientées dans un axe N-S, généralement individuelles, dotées d'un mobilier funéraire réduit constitué d'une seule céramique et de rares éléments de parure en coquillage et matière dure animale. La deuxième phase est composée de 30 sépultures orientées dans un axe NNO-SSE. Elles contiennent des inhumations individuelles et plurielles associées à des céramiques distinctes de celles rencontrées lors de la première phase et à des objets de parures, dont certains sont d'origine exotique, plus nombreux et plus fréquents. La troisième phase est représentée par une inhumation, exceptionnellement riche pour la nécropole. Le défunt était associé à 19 céramiques, une perle en pierre et une hache en bronze. Ce dépôt présente un parallèle avec des sépultures de la nécropole de Nyaung'gan située à 2,7 km de Oakaie 1. Notre analyse permet d'établir que les deux premières phases correspondent à une utilisation intermittente de la nécropole par une même population alors que la troisième marque une rupture lié à l'introduction du métal.

Abstract: In Southeast Asia, the late prehistoric period, from the appearance of farming to the rise of proto-states, lasts only 1500-2000 years, and is thus extremely brief in comparison to Europe. Cemeteries represent critical sites in the chronological and cultural understanding of these changes, stimulated by influences from both China and India. Myanmar is the only Southeast Asia nation to share terrestrial frontiers with both these vast neighbours, but in comparison even with Thailand and Viet Nam, archaeological investigation in Myanmar is in a phase of rapid expansion. As such, the late prehistoric dataset is beginning to offer opportunities for detailed and synthetic interpretations of this critical in the Sagaing Division of central Myanmar. Oakaie 1 is a well preserved cemetery at the heart of a rich archaeological area, which was investigated by the French Archaeological Mission in Myanmar (MAFM) between 2014 and 2016. As a result of these efforts, the Oakaie area has the most secure radiometric chronological sequence in Myanmar, with 52 determinations, and has been the focus of a number of advanced approaches, many of them firsts for the country. The excavation of the Oakaie 1 cemetery, during two four-week field seasons in 2014-15, lead to the exposure of 55 graves containing 57 individuals. This discovery gave us the opportunity to study the evolution of funerary practices in a single cemetery over a period of several centuries. The Oakaie 1 graves were cut in a hard volcanic tuff and filled with a more humid and brown soil, which made them extremely easy to recognize. The graves are arranged in well-defined rows, following one of two orientations, N-S or NNW-SSE. The graves are mainly single primary supine extended burials but some nine graves contain at least two individuals, and maybe more. One grave also contains the burial of a dog. The taphonomic analysis of the burials shows that most of the bodies decomposed within an open volume. The study of the constraints marked on the skeletons shows that a common type of container, a hollowed out tree trunk was probably used throughout the cemetery, with some differences in terms of narrowness. Taphonomic study of the multiple graves has failed to establish whether individuals were buried simultaneously. The main grave good is pottery, which was deposited in various places around the body, mainly on the lower limbs and during the filling of the graves. Some ornaments were found, consisting of beads, made of stone and shell, as well as bangles made of stone and animal bone. Only one grave, S15, furnished a metal artefact, a socketed bronze axe. Graves goods were quite sparse throughout the cemetery, as compared to its well-known neighbour, Nyaung'gan, with the exception of S15, which contained by far the most pottery, in addition to the sole bronze. The comprehensive study of the cemetery's spatial organization, the intercutting of the burials, the funerary practices as identified via taphonomic analysis, and the study of the grave goods lead us to propose three main phases of funerary use. The first is characterized by primary supine extended burials disposed in rows, with the graves oriented on a N-S axis. The burials were predominantly individual but three graves contained two individuals. Two further graves may also contain multiple burials. The phase one grave goods were very limited, a single pot of an almost universally homogenous form was placed during the filling of the grave. Ornaments made from shell or animal bone were rare. Two bivalve shells were found as a baby's grave good. The second phase of burials were also primary supine extended graves in clear rows but oriented on a NNW-SSE axis. The graves were mainly individual but multiple graves were nevertheless frequent, and systematically contain an adult with a child, in one case two children. The grave goods were mainly pots, deposited on the lower limbs of the individuals. The pottery assemblage could be clearly differentiated from the first phase in its style and presents an internally homogeneous group. Ornaments grave goods were more frequent and examples made from hard stone and in bangle form appear. Bivalve shell deposits were found within the grave goods of very young children, with the exception of one adult. The third burial phase is represented by a single grave containing one individual. This grave, S15, contains far more grave goods than any other in the Oakaie 1 cemetery, comprising 19 pots, one bronze axe and a stone bead. S15 represents a strong match to some of the burials at the neighbouring (2.7 km) cemetery site, Nyaung'gan. The three phases identified at Oakaie 1 could theoretically represent as many populations. However, the cultural basis of each phase is clearly inter-related and leads us to propose that the cemetery' the area that could be excavated at least - was used by the same population over cyclical periods for a substantial length of time. This model is supported not only by the taphonomic analysis but also that of the ceramics and the strontium isotope signatures. The third phase, representing the shift to the Bronze Age at around 1000 BC, cannot be evaluated in detailed due to a lack of evidence but shows that while funerary practices changed significantly, the individual is highly likely to be a descendent, culturally at least, of the two preceding phases.

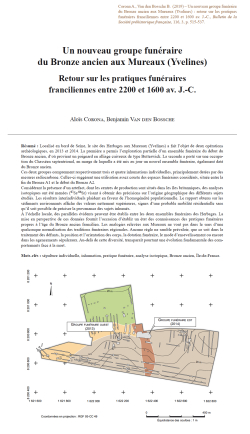

14-2019, tome 116, 3, p. 515-537 - Aloïs Corona, Benjamin Van Den Bossche — Un nouveau groupe funéraire du Bronze ancien aux Mureaux (Yvelines) : retour sur les pratiques funéraires franciliennes entre 2200 et 1600 av. J. C.

Un nouveau groupe funéraire du Bronze ancien aux Mureaux (Yvelines)

Retour sur les pratiques funéraires franciliennes entre 2200 et 1600 av. J.-C. / A new Early Bronze Age burial group in Les Mureaux (Yvelines): new perspectives on mortuary practices in Île-de-France between 2200 and 1600 B

Aloïs Corona, Benjamin Van den Bossche

Résumé : Localisé en bord de Seine, le site des Herbages aux Mureaux (Yvelines) a fait l'objet de deux opérations archéologiques, en 2013 et 2014. La première a permis l'exploration partielle d'un ensemble funéraire du début du Bronze ancien, d'où provient un poignard en alliage cuivreux de type Butterwick. La seconde a porté sur une occupation du Chasséen septentrional, en marge de laquelle a été mis au jour un nouvel ensemble funéraire, également daté du Bronze ancien.

Ces deux groupes comprennent respectivement trois et quatre inhumations individuelles, principalement datées par des mesures radiocarbone. Celles-ci suggèrent une utilisation assez courte des espaces funéraires considérés, située entre la fin du Bronze A1 et le début du Bronze A2.

Considérant la présence d'un artefact, dont les centres de production sont situés dans les îles britanniques, des analyses isotopiques ont été menées (87Sr/86Sr) visant à obtenir des précisions sur l'origine géographique des différents sujets étudiés. Les résultats interindividuels plaident en faveur de l'homogénéité populationnelle. Le rapport obtenu sur les sédiments environnants affiche des valeurs nettement supérieures, signes d'une probable mobilité résidentielle sans qu'il soit possible de préciser la provenance des sujets inhumés.

L'échelle locale, des parallèles évidents peuvent être établis entre les deux ensembles funéraires des Herbages. La mise en perspective de ces données fournit l'occasion d'établir un état des connaissances des pratiques funéraires propres à l'âge du Bronze ancien francilien. Les analogies relevées aux Mureaux ne vont pas dans le sens d'une quelconque normalisation des traditions funéraires régionales. Aucune règle ne semble prévaloir, que ce soit dans le traitement des défunts, la position et l'orientation des corps, la dotation funéraire, le mode d'ensevelissement ou encore dans les agencements sépulcraux. Au-delà de cette diversité, transparaît pourtant une évolution fondamentale des comportements face à la mort.

Mots-clés : sépulture individuelle, inhumation, pratique funéraire, analyse isotopique, Bronze ancien, Île-de-France.

Abstract: Located on the edge of the Seine River, the site of les Herbages in Les Mureaux (Yvelines) was the object of two preventive archaeology operations, in 2013 and 2014, in advance of the extension of industrial infrastructures used by Airbus and its subsidiary, Astrium Space Transportation. The first operation included the partial exploration of a mortuary group that yielded a Butterwick-type copper alloy dagger (Van den Bossche and Blin, 2014), from the initial stage of the Early Bronze Age. The second operation focused on an occupation from the beginning of the Chassean culture. On the edge of this occupation, a new mortuary group was discovered and dated to the Early Bronze Age as well.

Both sectors were strongly impacted by earthworks carried out in the 1960s to protect the military installations of the former Étienne Mantoux air base from potential flooding from the Seine. This work naturally affected the highest formations and sometimes reached the Protohistoric levels. It is probably responsible for the generalized leveling of the burial pits and the alterations of the exhumed osseous remains.

The two groups each contain three and four individual inhumations. Only one of the tombs contained artifacts. Most of the chronological information is therefore based on AMS radiocarbon dates realized by the University of Groningen (Netherlands) and the Beta Analytic laboratory in Miami, Florida. The dates of the mortuary group excavated in 2014 cover a relatively limited period from the middle of the 22nd century to the end of the 20th century BC. They suggest a short-term use of the mortuary space during the transition from the end of the Bronze A1 and the beginning of the Bronze A2 in Île-de-France and concur with the dates established for the mortuary group studied in 2013 (Van den Bossche and Blin, 2014).

Due to the exceptional presence of an artifact type whose production centers are located on the British Isles, isotopic analyses of the three best-preserved burials from the 2014 excavation were also realized, as well as of two inhumations exhumed in 2013. The aim was to confront the 87Sr/86Sr signal recorded in the bioapatite of the dental enamel of the individuals in question to obtain information on their geographic origin(s). The interindividual results argue in favor of a homogeneous population for the groups identified in 2013 and 2014. The signature obtained for the neighboring sediments, on the other hand, show much higher values. These significant variations between the human and local sedimentary signals probably indicate residential mobility, though it is not possible to identify the provenance of the inhumed subjects or to determine the period in their life during which this hypothetical migratory episode would have occurred.

At the local scale, clear parallels can be observed between the two mortuary groups at les Herbages. These consist of small areas covering a few dozen square meters containing a handful of slightly dispersed tombs. The mortuary practices identified have many points in common. All the burials studied correspond to primary individual inhumations contained in simple, most often large, pits. The bodies, most often in the supine position, are oriented in the east-west axis, with the head most often at east. A significant difference is seen in the artifact, which is found in only one of the burials.

Replacing these data within their broader context enables us to review our state of knowledge of the mortuary practices of the Early Bronze Age in Île-de-France. Paradoxically, the few analogies observed at Les Mureaux do not indicate any normalization of the regional mortuary traditions. Even if the available corpus is still small (38 burials distributed among 23 sites), it appears that there was no dominant rule, whether in the treatment of the deceased, the position and orientation of the bodies, the grave goods, the burial method, or the arrangements of the graves. Despite this diversity, there appears to have been a fundamental evolution of behaviors concerning death tending toward a greater focus on the individual and leading to a multiplication of small mortuary units, which is very different from the typical models from the end of the Neolithic.

Keywords: individual burial, inhumation, mortuary practices, isotopic analyses, Early Bronze Age, Paris Basin.

13-2019, tome 116, 3, p.479-513 - Benoît Sendra, Marylise Onfray, Ambre Di Pascale, Maxime Orgeval, Laurent Bruxelles - Étude d'un fossé et d'architectures en terre fondés au milieu du 3e millénaire av. J.-C. sur le plateau des Costiè

Étude d'un fossé et d'architectures en terre fondés au milieu du 3e millénaire av. J.-C. sur le plateau des Costières (Garons, Gard, France)

A study of a ditch and earth architecture founded in the middle of the 3rd millennium BC on the plateau des Costières (Garons, Gard, France)

Benoît Sendra, Marylise Onfray, Ambre Di Pascale, Maxime Orgeval, Laurent Bruxelles

Résumé : Localisées non loin du site de Puech Ferrier et de l'enclos inédit de Mitra II fouillé en 2011, les enceintes de Mitra III situé à Garons (Gard) ont fait l'objet d'une première campagne de fouille préventive en 2012. L'exploration sur une superficie de 5 000 m² a révélé la partie méridionale et une porte d'un établissement délimité par au moins deux systèmes de fossés d'enclos qui se succèdent au cours d'une période qui connait le développement du Fontbouïsse, l'impact Campaniforme et l'émergence du plein Bronze ancien (BA2), soit entre le 27e et 24e s. av. J.-C. L'article traite spécifiquement de l'étude d'un imposant fossé plus large, plus profond et de plan plus anguleux que ceux du premier système d'enceinte dont il vient condamner l'accès. Il a été observé sur près de 90 mètres linéaires et délimite le sud de l'établissement. Il présente un puissant niveau de comblement constitué d'éléments d'architectures en terre crue en connexion partielle, surmontant une couche limono-cendreuse dont le spectre anthracologique est très largement dominé par le chêne.

Sur la base des résultats de l'analyse stratigraphique, micromorphologique et une caractérisation micro et macroscopique des éléments de terre crue, il est possible de caractériser la dynamique de comblement et la nature de l'architecture en lien avec ce système de délimitation.

Mots-clés : enceinte fossoyée, Néolithique final, France, architecture en terre, technique constructive, évolution fonctionnelle des enceintes.

Abstract: The purpose of this paper is the detailed study of one of the excavations that has marked the evolution of Fontbouïsse of MITRA III located in Garons (Gard, France) whilst focussing on the development and the disappearance of enclosures in the south of France.

The site located near to a site known as Puech Ferrier, an unpublished enclosure of MITRA III excavated in 2011, was first excavated in 2012 within the framework of preventive archaeology. This exploration of a 5000 m² surface revealed the southern part and the entrance of an installation delimited by at least two ditches which succeed one another, dating

to a period between the 27th and 24th centuries BC that includes the development of the culture of Fontbouïsse, the Campaniforme (Bell Beaker) and the emergence of the early Bronze (BA2). A network of three concentric ditches, the innermost enclosure being the oldest, makes up the first enclosure, where an interruption in the ditches allows access to the site. A later much larger wider and deeper ditch cuts across the first enclosure.

The paper focusses on the study of this ditch and its fill, which is the only enclosed site dating to the Late Neolithic in the south of France. Observed over nearly 90 m, this ditch delimits the southern part of the site. It contains fragments of mudbrick over a silty ashy layer the anthracological spectrum of which contains mainly by oak. Based on the results of stratigraphic and soil micromorphology, a phased filling of the ditch can be proposed. Micro and macroscopic characterization of the earthen elements found in the ditch have specified the nature of the cob and wattle and daub and the demolished structure they came from.The findings reveal that the ditch remained open for a relatively short period of time, after which a cob structure, perhaps a wall, was installed, the base of which is preserved in a portion of the ditch. The ditch was then filled in by the destruction of another earthen and wood structure.

This architecture could have been used to strengthen the monumental aspect of the enclosure, the hypothesis being that it copied a layout observed on other Fontbuxien settlements. A violent fire subsequently destroyed this ditch-wall enclosure and a possible adjoining building. Following on from this event, the ditch was re-dug before being filled in after the site is abandoned.

The exact dating of the ditch and the destruction of the earthen wall remain imprecise.

Some elements found in the lower ditch fill date to the first phase of the Fontbouïsse culture. They stylistically refer productions from the plain of Hérault and Gard. However, the destruction of the earthen architecture is dated by radiocarbon analysis and pottery found in the upper layers and the discovery of a sherd with international style decoration gives a later dating range of between 2450 and 2250 cal. BC. This enclosure and its destruction constitute a milestone in Fontbouïsse and Late Neolithic chronology. Its foundation and destruction occur within a short space of time. The events that occurred during the history of MITRA date the

initial foundation and development of the concentric enclosures and the site's total overhaul, which happened shortly before its abandon. The entrance identified at Mitra III, the new ditch with its earthen architecture that cut across the first enclosure around 2500 cal. BC questions our knowledge of the development and disappearance of enclosures at a pivotal period (Late Neolithic-Early Bronze Age) in southern France.

Keywords: causewayed enclosure, Late Neolithic, France, earthen architecture, building technique, functional development of enclosure.

12-2019, tome 116, 3, p.455-478 - Anaïs Vignoles, Laurent Klaric, William Banks, Malvina Baumann — Le Gravettien du Fourneau du Diable (Bourdeilles, Dordogne) : révision chronoculturelle des ensembles lithiques de la « Terrasse inférieure »

Le Gravettien du Fourneau du Diable (Bourdeilles, Dordogne)

Révision chronoculturelle des ensembles lithiques de la « Terrasse inférieure » / The Gravettian at Fourneau du Diable site (Bourdeilles, Dordogne): chronocultural review of the lithic assemblages from the lower terrace

Anaïs Vignoles, Laurent Klaric, William E. Banks, Malvina Baumann

Résumé : En France, le Gravettien moyen est caractérisé par deux faciès lithiques : le Noaillien, marqué par la présence de burins de Noailles, et le Rayssien, identifié par la reconnaissance de la « méthode du Raysse ». Malgré un important recouvrement géographique, le territoire d'expression du Rayssien semble plus septentrional que le Noaillien, ce qui a été à l'origine de nombreuses hypothèses. Cependant, il se peut que l'estimation de leurs aires de répartition géographique soit biaisée, puisqu???un examen de la littérature révèle une forte disparité dans le degré d'informations disponibles pour chaque site. Le site du Fourneau du Diable (Bourdeilles, Dordogne) illustre ce biais. Fouillé dans les années 1910-1930 par D. Peyrony, ce site a été successivement attribué au Gravettien ancien, au Noaillien stricto sensu et au Rayssien. La reprise récente des fouilles (dir. M. Baumann), permet de reconsidérer ces attributions et de préciser les biais induits par les méthodes de fouilles anciennes.